In January 2021, as Kani Kusruti went on-stage to receive Kerala’s 50th State Film Award for Best Actress in Biriyaani, she wore Rihanna’s Universal Red Lipstick from Fenty Beauty. This was not by chance. Kani went on to explain the politics behind her choice on Instagram. Referring to a BuzzFeed article, she wrote how her act was a subversion of the narrative that both fetishises as well as ridicules dark-skinned women for wearing red lipstick, because of the assumption that only fair-skinned women can carry off the colour.

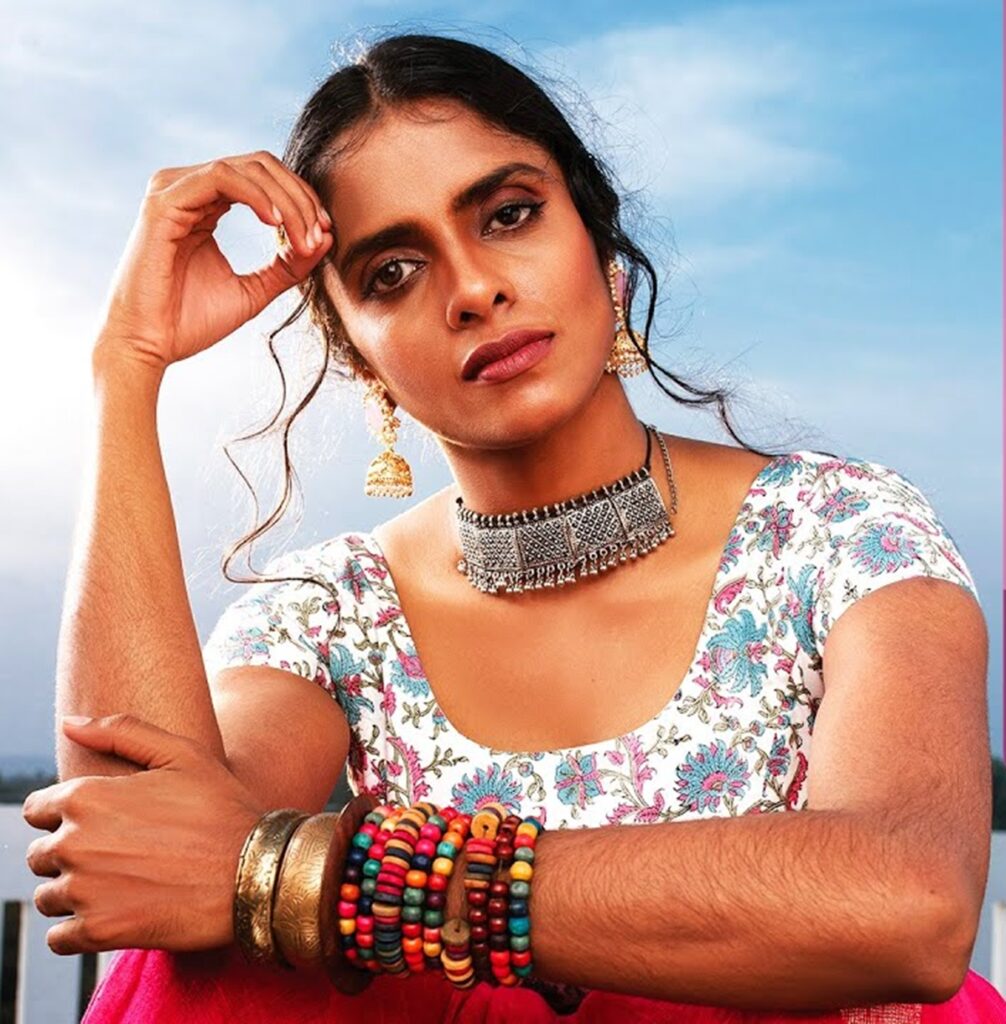

This is not the first time Kani, currently riding high on the success of science-fiction comedy drama Hotstar series OK Computer and her widely-acclaimed Malayalam film Biriyaani, has instrumentalised her body to emphasise on her gender politics. In 2020, when Grihalakshmi, a popular Malayalam fortnightly magazine approached Kani for a photoshoot for their December edition, she had categorically told them that she wanted to wear minimal make-up and wished to have her body hair untouched by make-up and/or photoshop.

In an exclusive interview to feminisminindia.com, Kani said that this space to assert one’s choice is usually limited in most photoshoots. “When brands approach us for modelling or shoots, they have a very specific idea in their mind about the way they want to sell their product and hence, the space to negotiate is considerably lesser in such shoots. However, I was approached by Grihalakshmi after the Kerala State Awards were announced. The shoot was about me and I wanted to be represented the way I am.”

But when the magazine went to print, the cover showed Kani gazing into the camera intently, with one hairless and considerably smoothened arm touching her neck-piece and the other airbrushed arm callously touching her hair. Meanwhile, the photos inside the cover came out the way she wanted: her skin texture and body hair minimally interfered with.

Kani believes this to be a miscommunication on the part of Grihalakshmi and the publishers: “They must have sent the copy to print without specifying what I had required, who would, in turn, have airbrushed the cover image like they usually do with all covers.” She found this a careless slip-up on the magazine’s part.

“However, I understand that taking this stand comes from a position of some privilege,” adds Kani, given how many people are still struggling to make a mark in the industry and despite how they mobilise on the right kind of politics, their choices are limited, considering how even today’s so-called progressive cinema continues to cater to the conventional gaze. “But it is important to question things to start with, even if not radically so,” Kani quips.

In addition to making her gender politics clear in real life, on reel too, Kani has been associated with rare projects situating a woman’s sexual agency and liberty within her own body, on her own terms. The 35-year-old actor from Kerala, with strong roots in theatre, has been a part of two short fiction films: Memories of A Machine and Counterfeit Kunkoo — the former depicting a brief conversation on masturbation between a woman and her partner, and the latter, a take on how a survivor of marital rape struggles to find a room of her own in Mumbai.

These short films are especially interesting in how they explore sexuality: In Memories of a Machine directed by Shailaja Padindala, Kani’s character speaks about how she began exploring her body following a brief (and pleasurable) encounter she had with a much older man when she was in school. In Counterfeit Kunkoo directed by Reema Sengupta, Kani’s character, Smita, a survivor of marital rape, upon finally finding a flat, finds herself taking her pleasure into her own hands. For an entire generation and more of women grappling with the orgasm gap, many of whom are introduced to anything remotely (and often disappointingly) sexual only and once they are married, those surviving rapes within their marriage and confused how to make sense of it, this is a scene that speaks loudly even with no dialogues.

Kani, however, despite being an artiste, does not believe that changes in mindsets and narratives can be brought about radically, as often progressive art is expected to do. “I personally like to think that social changes are more systemic and institutionalised — by making, amending and engaging with policies. For bringing about any change, I prefer falling back on scientific rigour and verifiable, tangible data unlike cinema where there’s a certain ambiguity and a subjective bias.”

But it is not that the actor thinks art is not a powerful medium. “It is, and I look up at people capable of informing change through art in admiration and awe,” she further explains. Kani believes that radical changes and revolutions happen every day and these cumulatively and sustainably lead on to a systemic change. “I stand by many radical social and human rights movements in solidarity, but I gravitate more towards incremental systemic organisational change. However, these two are not mutually exclusive — one responds to acute problems the other to chronic ones. Both can very well happen in tandem,” she says.

Which is why Kani’s strong stand demanding more equitable opportunities and visibility to people from underprivileged communities have always been in tandem with her more strategic suggestions such as a petition to the government to employ more women in the technical and production crew, scholarships and grants for students from Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi backgrounds to get into film schools, etc. Kani has often dedicated her felicitations and awards to PK Rosy, the first woman actor in Malayalam cinema and a Dalit woman from the Pulaya community who portrayed the role of an upper-caste Nair woman. The Malayalam industry’s Women in Cinema Collective, launched in 2017, has dedicated its film society to PK Rosy. Kani, who was briefly a part of the WCC, had made some of these suggestions to Dr Asha Achy Joseph, one of the founders of the collective.

Also read: P K Rosy: The Dalit Malayali Actress After Whom WCC Named Its Film Society

In June 2020, the Community Cinema Collective in Kochi planned to produce films with an all-women crew belonging to different caste and class communities, to subvert the deeply entrenched gender and caste-based discrimination people in Indian cinema has faced until now. “The age range of the script writers are from 30 to 60 and they include four Kudumbashree workers. The project is being conceived with the support of Sacred Heart College, Thevara,” Asha Achy Joseph, also the coordinator of CCC, had reportedly said.

Kani does not deny that the general state of security and safety a woman experiences in India is so less that many hesitate to step out of their houses after 7 in the night. At the same time, Kani also believes that if there is affirmative action to ensure women get opportunities to work in production and technical spaces in cinema, more women who had earlier not even thought of joining the industry as a career option, would begin to reconsider.

“Definitely, there are women working as assistant directors, assistant choreographers, costume designers and make-up artistes. I have also seen some trans people working in the make-up department. However, I have never seen a woman work as a gaffer or as a focus puller in the technical field, which is work that requires technical precision and engineering (as against artistic intuition and design thinking). Nor have I seen women employed in taking tracks and lifting heavy lights, because the assumption is that only men can do the heavy lifting work that requires brute force. But when women are involved in labour that requires their physical strength in their everyday lives, I don’t see why they should not be employed in the production and technical departments,” says Kani.

One common argument raised against employing more women in these spaces is based on security concerns, lack of proper toilet facilities for women and shift timings. However, we belong to a state where many women are employed as nurses and compounders working odd shifts, then is that a strong argument at all, Kani points out. One of the primary concerns raised by the WCC for the women in the industry was security issues and better toilet facilities for the women. Actor Innocent, who was the president of AMMA (Association of Malayalam Movie Artists) in 2017, had acknowledged the lack of facilities for women on the sets, except for the lead actress. “Because the producers can’t afford them,’’ he had told the Times of India.

Kani has also observed that comparatively, people from economically underprivileged communities have had to struggle harder for opportunities to work in the production and technical departments. “Someone who is equally talented but belongs to a more privileged economic background might agree to work for free or for lesser money as they gain experience in return. Many producers would then prefer to employ them than someone for whom the wages is a necessity,” she explains. However, the most evident lack of representation of people from all strata of society continues to be in the visual world of cinema, Kani states.

On camera, this stratification is evident, considering we still do not have any Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi actors in the mainstream, for instance. Even though the Malayalam film industry can boast of Kalabhavan Mani, the legendary Dalit actor and singer, he too, found himself often relegated to portraying caricaturised side-kicks and villains among a handful of protagonist roles. Even in the recently released Netflix anthology Ajeeb Dastans, Dalit filmmaker Neeraj Ghaywan’s short on Dalit queer love, titled Geeli Pucchi, the leads are played by upper-caste actors Konkona Sen Sharma and Aditi Rao Hydari.

Kani’s conscious and sustained quest to challenge the normative is as much her own as it is an extension of her parents’ unconventional and subversive ways of being. The daughter of social activist and community health expert Dr Jayasree AK (whom she calls Jayasree chechi) and human rights activist Maitreya Maitreyan (whom she calls by his name), Kani’s upbringing has been a rational and thoughtful take on parenting by Indian standards. In July 2020, Kani took to Instagram to share a letter Maitreyan had written to her when she had turned 18—an example of the said radical form of parenting.

While Kani attributes a large part of what she is as the work of her parents, she expresses similar gratitude for filmmaker and her partner Anand Gandhi. “I often think that if I was a very rich person, I would have put all my money on Anand and people like him, because at least in India we do not see a lot of investors in intelligent and great minds like his. They are capable of changing this world, people just do not recognise this,” says Kani.

Despite the ideals that Kani has had the privilege of being exposed to since childhood, what makes her politics real is how she pragmatically approaches life. Throughout the almost two-hour long Zoom interview, what stands out is how Kani, not for once, attempts to project herself as a torchbearer or the beacon of perfect politics. There is no air of presumption around her. Instead she is as fidgety yet candid as you and I get when we get a video call we are probably not ready for. She accepts that her stand comes from a position of certain privilege, understands that idealism does not pay bills and that working with those of differing ideologies is a choice we make in a democratic space, because “everything is not black and white”. “Unless it reaches a state of unbearable extremity, then I step back and disengage,” she says.

Yet, what Kani calls her life project is to keenly observe people and their responses to their environment—where do their prejudices come from, what triggers them, whether she can have a dialogue with them while disagreeing on each others’ politics and working with each other. And for the same reason, Kani’s feminist politics is not one that aligns with the extremities of cancel culture now very prevalent on the Internet. “I am not advocating that we put up with and justify abuse. But it is important that in a system of accountability and restorative justice, we do not completely cut off people, especially the ones who have wronged us. There has to be a room to engage with those expressing remorse,” she says. But then again, Kani emphasises that this varies from case to case.

“The same measures of justice cannot be used for a person who has been perpetrating abuse on multiple people over a long period of time as for someone who may have violated the rights and wellbeing of someone once, but is showing willingness to repent, repay and reform. Crime and punishment have various thresholds,” she asserts.

Also read: Film Review: Biriyani – A Gripping Take On The Life Of Muslim Women In Kerala

Kani Kusruti’s much-acclaimed film Biriyaani, is amassing recognition from around the world. Having won the Best Actress Award in the BRICS Competition Section at the 42nd Moscow International Festival, the special mention at the 67th National Film Awards, 50th Kerala State Award for best Actress, among many others, Biriyaani is all set for an OTT-release on Cave Stream on April 21, 2021.

On the work front, Kani’s much-acclaimed film Biriyaani, is amassing recognition from around the world. Having won the Best Actress Award in the BRICS Competition Section at the 42nd Moscow International Festival, the special mention at the 67th National Film Awards, 50th Kerala State Award for best Actress, among many others, Biriyaani is all set for an OTT-release on Cave Stream on April 21, 2021. Kani plays the character of Khadeeja in a loveless marriage with an older man and is battling the stigma around the identity of a Muslim woman in India. The film’s relevance is amplified in how in an India where we see an evident rise in hate crimes against Muslims in India, Kani portrays Khadeeja’s desolation with such precision, that we will find ourselves facing uncomfortable questions around religion and patriarchy, whether we choose to or not.

Featured image source: Latestly

About the author(s)

Soumya is a Masters graduate in gender from Jamia Millia Islamia & has a PG Diploma in New Media from Asian College Of Journalism. She is learning to unlearn and question patriarchal structures with empathy. She has taken an interest in gardening but has over-watered and killed two plants already. This may or may not be a metaphorical reference to how she deals with life.