Seventy years after Independence, it is very clear that we need to redress the paradigm of development envisaged by the Indian state. The current model of development has failed to bring sustainability and balance economic interests with the development of large sections of the population. The development model that promises substantial equality in turn privileges corporate interests at large. Displacement has been one of the major repercussions of this institutional inefficiency, particularly among the tribal, indigenous and forest dwelling communities.

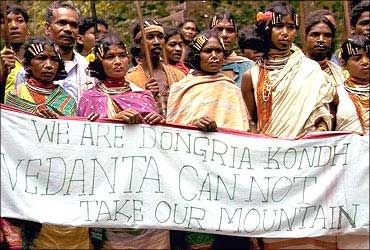

The paragon of ‘vikas’ that India has followed has been equivalent to a transfer of resources from the weaker sections to the privileged ones. Tribal populations are the worst affected victims of development, because traditionally they have inhabited resource rich regions which hold most of the country’s mineral reserves such as coal, bauxite and mica

The United Nations defines Internally Displaced Persons(IDPs) as “Persons or groups who have been forced to flee their homes suddenly or unexpectedly in large numbers as a result of armed conflict, internal strife, systemic violation of human rights or natural or man-made disasters, and who are within the territory of their own country”. While the case of ineffective rehabilitation programmes undertaken due to naturally induced displacements can be seen as bureaucratic inefficiency, involuntary and forced displacements become a matter of human rights violation and systemic injustice for the marginalized.

According to a study conducted in 2011, around 21 million people have been internally displaced in India due to ‘development’ projects. The recent figures show that out of these, the 40% Adivasi communities are the most vulnerable. The paragon of ‘vikas’ that India has followed has been equivalent to a transfer of resources from the weaker sections to the privileged ones. Tribal populations are the worst affected victims of development, because traditionally they have inhabited resource rich regions which hold most of the country’s mineral reserves such as coal, bauxite and mica. The consequence of the present pattern of development is the powerlessness of the tribal sections due to displacement and insufficient compensation provided through rehabilitation projects.

Since Independence, the development projects enlisted under the Five Year Plans have displaced nearly five lakh persons each year. However, this figure fails to take into account the land acquisition cases by non-plan projects as a result of change in land use, acquisition of land for urban growth, hydro electrical, thermal and industrial projects. These fallacious endeavors successfully lead to destruction of habitats and displacement induced loss of livelihood, environmental degradation and pollution.

Further,studies have shown that women as marginalized members within the highly patriarchal and impoverished communities are forced to shoulder the ordeal of displacement far more intensely in the form of loss of livelihoods and property rights, exposure to physical violence, bad marriages and overall deterioration of status

The displacements cause a downward spiral of impoverishment for the tribal population with the psychological and sociological consequences that come along with it. It causes dismantling of production systems, erasure of ancestral heritage and destruction of land, scattering of kinship and familial groups. This makes tribal communities vulnerable to urban environment, disassociation with informal social networks and capital for mutual support, disruption of trade and market links for livelihood and weakening of complex community relationships that provide avenues for political representation in matters of conflict and injustice.

Thus, the very cultural and social identity of the internally displaced persons is subject to severe incursion by the development projects initiated by the State, hence making it a matter of structural injustice and violence. Land alienation, loss of access and control over forests and indebtedness due to loss of livelihood have become key reasons for marginalization of Adivasi communities. Further, studies have shown that women as marginalized members within the highly patriarchal and impoverished communities are forced to shoulder the ordeal of displacement far more intensely in the form of loss of livelihoods and property rights, exposure to physical violence, bad marriages and overall deterioration of status.

Also read: In Posters: How Will The Draft EIA 2020 Affect Adivasi and Tribal People?

An ethnographic research in two most erosion-prone blocks in the Malda district of West Bengal, which represents a unique situation of displacement caused both by a development project, namely the Farakka Barrage, and an ecological factor, i.e. the shifting of the course of river Ganga, attempts to understand the specific ways in which local institutions in host areas (which are mostly rural) help in the everyday coping and survival of displaced women. It notes that the National Resettlement and Rehabilitation Policy (2007) initiated by the Indian Government does not take into consideration the importance of these institutions in facilitating mechanisms that connect households to local resources and further help to elevate the condition of women in displaced areas.

The vulnerability to climate change is a function of socio-political and institutional factors and may vary depending on the institutional affiliation and interconnectedness of the vulnerable communities displaced. Thus, local institutions are crucial in providing external support and facilitating interventions between national policies and the displaced social groups. Women are one such social group, who are vulnerable to both natural and forced displacements due to their social, political and economic subordination in patriarchal societies like India. The diminishing psychological capacity to bear the loss of livelihoods leads several men to resort to conspicuous consumption of liquor which may exacerbate gendered violence.

Forced relocation usually results in people being transplanted from a familiar social ecology to an alien one , in which they are not only vulnerable but also live as underclass communities as they fail to adapt to the new socio-cultural and economic milieu. In most cases, resettlement sites are underprepared in terms of basic education and health infrastructure required for the tribal and indigenous communities to habituate and acculturate to the host ecosystem.

According to a study by The Wire at Sunabeda in Nuapada district of Odisha, the Gond, Bhunjia Adivasis and the Paharia community were denied access to livelihood and cordoned off by applying restrictions on the sale of Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFP). This was done to steer up the upgradation of the Sunabeda area into a Tiger reserve and eventually force the inhabitants to surrender their land by applying strict regulations on the trade business. They were subject to destitute conditions and shunned from procuring forest produce which was their prime source of livelihood. Owing to the structural failure to expedite basic healthcare support systems to the Adivasi communities in Sunabeda, the shrinking livelihoods has significantly impacted their life expectancy as they now have to incur out of pocket expenditure.

The community has been impelled to mortgage ration cards for local credit or for procuring cash to meet their healthcare needs. The study concluded that the community lagged behind on several national averages on many public health indicators. This definitely calls for immediate attention to the systemic catastrophe and failure to provide basic needs to these communities. The general poverty and dispossession of people to resources demands for institutional and structural redressal.

Rehabilitation as a process should intend to reverse the risk of resettlement for the communities displaced due to ecological factors. The focus should be on landlessness to land-based settlements, joblessness to re-employment, food security to safe nutrition, homelessness to house reconstruction, social disarticulation to social inclusion and deprivation of common property resources to inclusive community reconstruction

Resettlement programmes predominantly focus on the process of physical relocation rather than social and economic development of the internally displaced people. According to reports, the risk to adversely affected people is not a component of the conventional rehabilitation projects. The factors that adversely affect the tribal population are from changed access to or control of productive resources by the development projects instituted in these regions. The cost of resettlement offered to the tribal communities is invariably underestimated and under financed. Institutional weakness marked by inefficient coordination among the various departments aggravate their slavish conditions.

The legal recourse requires IDPs to turn to fundamental rights of Article 21, Article 39 and Article 41 for restoration of justice. The Land Acquisition Act which provides for fair compensation at market value fails to cater to the policy framework for the rehabilitation process. In the absence of legal and policy instruments that would guide the rehabilitation process in India, even organisations with well structured staff have failed in their consistent efforts for effective resettlement. Rehabilitation as a process should intend to reverse the risk of resettlement for the communities displaced due to ecological factors. The focus should be on landlessness to land-based settlements, joblessness to re-employment, food security to safe nutrition, homelessness to house reconstruction, social disarticulation to social inclusion and deprivation of common property resources to inclusive community reconstruction.

Also read: Niyamgiri Movement: Questioning The Narrative Of Developmental Politics

The Constitution guarantees us the right to citizenship. The judiciary is responsible for translating this constitutional mandate into practical terms and conduct trials to ensure that these rights are not violated. However, Usha Ramanathan in her paper on ‘Displacement and the Law’ in the Economic and Political Weekly, explains that despite these constitutional safeguards the judiciary is biased against the displaced tribal and Adivasi population. She quotes that the “statute law determines the process by which the relationship between a community and its resources may be affected, even as it redefines rights”. Hence, judicial apathy is a reason for supposedly ‘preferential’ treatment of the displaced communities being against the ‘equality’ promised in the Constitution.

Featured Image Source: The Wire

About the author(s)

Mansi Bhalerao is an Ambedkarite feminist, an undergraduate at Miranda House. She is an aspiring student of Sociology, trying to navigate and assert her praxis.