Sports tournaments have always allowed us to live vicariously. We sit, cosily nestled, in our armchairs of privilege (metaphorical and corporeal) and live all too briefly through the bronzed, lithe bodies we see on our screen interfaces. This has served all too useful during the long COVID days, as we continue to distance, bereft of opportunities to meet each other in person, and with communal activities in the great outdoors tantalisingly out of reach.

We can’t run, jump or play ball like we used to, but we can certainly watch people play these sports on screen, in our protected bubbles that attempt to defy the pandemic. The grit, effort and wins of athletes at events like the Olympics and other platforms sure make us proud and must be celebrated.

It is hard to miss that there exists a thin veneer of patriotism and nationalism – the fallacy of believing in the preordained supremacy of one’s own country through an accident of birth – coating these sports tournaments. One might be better off not dwelling on the tenuous distinction between patriotism and nationalism. It is a slippery slope reminiscent of the Hinduism versus Hindutva debate.

A harmless pursuit, one might say, to live through sportspeople. We break no quarantine rules, we shed no blood, we wage no wars. We live vicariously and similarly, through novels, movies, series, video games and other forms of engagement. The only distinction lies in the fact that in the latter pursuits, we engage with fictional characters, while in sports, we involve with real people.

The problem occurs when we consider our vicarious living as an investment in the lives of sportspersons. We watch them, we follow them, we help them build a career through our support and therefore, we tend to believe that we own them, or parts of them. Their success is something we take pride in (despite doing little or nothing to help athletes afford the equipment or training they deserve).

This problem is, as is the case with most problems, gendered. Sportswomen are usually afterthoughts in tournaments, our occasional exultation over Serena Williams or P.V. Sindhu aside. PayScale estimated the gender pay gap in sports to be at 94% in 2021. Men in cricket in India earn 14 to 30 times more than women and Mithali Dorai Raj, India’s national Test and ODI team captain does not yet feel ready to ask for pay parity

Their failure is a personal betrayal to us and we feel they must must be punished appropriately like in the unfortunate case of Vandana Katariya and her family being subject to casteist hooliganism after loses in field hockey at the Olympics. We believe we own our athletes and their bodies.

This problem is, as is the case with most problems, gendered. Sportswomen are usually afterthoughts in tournaments, our occasional exultation over Serena Williams or P.V. Sindhu aside. PayScale estimated the gender pay gap in sports to be at 94% in 2021. Men in cricket in India earn 14 to 30 times more than women and Mithali Dorai Raj, India’s national Test and ODI team captain does not yet feel ready to ask for pay parity.

Implicit beliefs of ownership, therefore become even more acute over women and their bodies in sports. Women, after all, have not until recently been able to conspicuously attempt to establish their ownership over their own bodies, either in the community or in legislations. The USA has enacted 90 laws on women and their right to seek abortion this year, the most in any year to date.

The Kerala High Court in India has recently recognised that a sexual act that mimics penetration amounts to rape and that marital rape is a ground for divorce, in two separate verdicts. India’s COVID vaccination drive continues to show a gender disparity underlining long-standing, evident barriers in access to healthcare. Clearly, we’re still not sure if adult women can make decisions about their health and bodily autonomy.

P.V. Sindhu, Manika Batra, Kamalpreet Kaur, Chanu Saikhom Mirabai, Mary Kom, Lovlina Borgohain, Aditi Ashok and Vinesh Phogat have had their bodies and performances scrutinised in proprietary fashion by spectators of the world’s largest democracy, who choose to call them “the nations’ daughters” in fine patriarchal mettle

This isn’t new, though the furore over the French Open and the Tokyo Olympics have certainly brought this into sharp focus. To recapitulate, over the past month, the Norwegian women’s handball team were ludicrously fined 1,500 euros in the Euro 2021 sports tournament for choosing to wear thigh shorts rather than bikini bottoms – implying their role is decorative rather than performative.

A British Paralympian was told her track shorts were far too short, the subtext being that there is something shameful and liable to be covered up, about being a person with disability in general, and cerebral palsy, in particular. The press and organisers at the French Open took umbrage at Naomi Osaka refusing to let them into her personal space (what else is an interview about) during the tournament, triggering the athlete to disclose her struggle with depression and withdraw from the Open.

Also read: Male Gaze & The Policing Of Sportswomen’s Bodily Autonomy

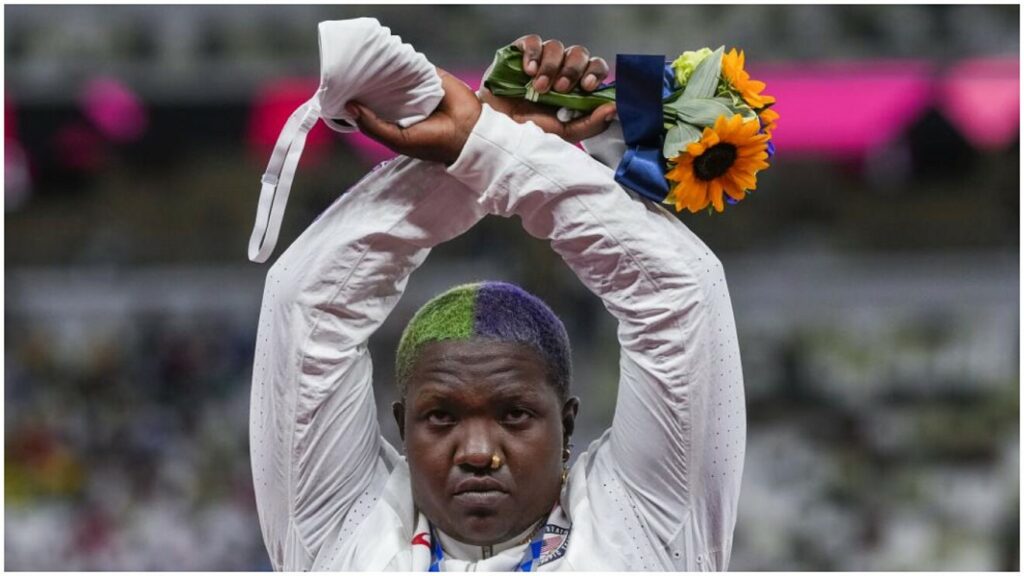

Simone Biles faced flak for refusing to put her body at risk by doing the Yurchenko double pike and for withdrawing from individual and team gymnastic events at the Olympics, while still recovering from past mental health trauma. Raven Saunders, queer athlete and person of colour, faced investigation for symbolically representing an X (for intersectionality) on the Olympic podium after winning the silver medal in women’s shot put.

Of Indian athletes at the Olympics, Vandana Katariya and the women’s field hockey team faced casteist abuse for having “too many” Dalits (how many is too many – is one allowed?) which the Indian Government and assorted sports regulatory authorities remain ominously silent on.

P.V. Sindhu, Manika Batra, Kamalpreet Kaur, Chanu Saikhom Mirabai, Mary Kom, Lovlina Borgohain, Aditi Ashok and Vinesh Phogat have had their bodies and performances scrutinised in proprietary fashion by spectators of the world’s largest democracy, who choose to call them “the nations’ daughters” in fine patriarchal mettle.

Mary Kom’s tattoos received intrusive attention and trolling, with assorted sons of the soil implying that the cross on her deltoid (and flaunting her identity as a Christian) played a role in her missing out on a medal this time around. Manika Batra has, in a turn of events that echoes Naomi Osaka experiences, been issued a show cause notice by the Table Tennis Federation of India for her refusal to let the national coach, a man she appears clearly uncomfortable with, stay by her side at matches.

Certainly these incidents raise important questions we must ask ourselves about the sportswoman and her autonomy. Playing at international sports tournaments carries prestige, no doubt. It is both an honour and a burden to have the expectations of a nation rest on one’s wrists or shoulders.

In a world where women are still far less than equal, to be a sportswoman is far more burdensome. What price, though, do we expect the sportswoman to pay for being allowed to play a sport that she loves, and play it well, on a big stage, in front of a large group of people?

These aren’t questions restricted to sports alone. All professions seem to require some degree of the commodification of the body – and clearly more so of women than men. With the ending of the Olympics and India having demonstrated its best ever performance, most of it driven by women, the sportswoman and the objectification of her body for mass public consumption and medication seems particularly rife and hard to turn away from

What does the sportsperson owe us, as spectators? Do we expect control over their race, ethnicity, caste, how tall they may be, how much they may weigh, whom they may love (Sania Mirza or Dutee Chand), what they may wear (Sania Mirza, again), who gets to intrude into their personal spaces (coaches or journalists or endorsements), their political affiliations, their opinions, their very self?

A deeper question we must then ask ourselves is that if we expect the sportswoman to surrender her body and its functions to our policing, what part of herself remains to her own autonomy?

May she slip her toenails or curl her lashes without asking us or do we expect the nation to determine that as well? What must a woman give over to her audience in return for a platform on which she may demonstrate her mental and physical prowess? Does the sportswoman’s body belong to herself? It appears not.

These aren’t questions restricted to sports alone. All professions seem to require some degree of the commodification of the body – and clearly more so of women than men. With the ending of the Olympics and India having demonstrated its best ever performance, most of it driven by women, the sportswoman and the objectification of her body for mass public consumption and medication seems particularly rife and hard to turn away from.

It remains to be seen if the nation that declares them its daughters (without permission) will now address the sexist and casteist abuse they are vulnerable to.

Also read: No Sports/Sponsorships: Dual Pandemic That Hit Sportswomen Globally

Featured Image Source: Scroll

About the author(s)

Migita is a psychiatrist, currently training as a resident doctor in geriatric psychiatry. She is originally from Kollam, Kerala. She grew up and did her schooling in Dubai, before relocating to India to pursue a career in Medicine. She completed her MBBS from Government Stanley Medical College in Chennai and her MD in Psychiatry from at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore. You can find her on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn and Medium.