The Dalit Feminist Theory: A reader has remarkably captured the essence of the debates and trajectory essential to engage with Dalit feminist thought, outlining the history of struggle Dalit women have fought against sexual violence. Steven Lukes’ A Radical View Of Power and Sandra Harding’s ‘Epistemology of Rainbow Coalition Politics’ are insightful theoretical frameworks for analysing forms of violence.

In India, varying forms of violence such as the practice of devadasi, sati, widowhood and child marriage have been molded into the power structures and accepted as a ‘norm’. Luke gives us a psychoanalytic perspective by showcasing how oppressive communities use clairvoyant techniques to shape the thought process of other people and to exercise control over them. “The superposition of endogamy on exogamy means the creation of caste”. The unique collision of patriarchy and brahminism (upper castes rituals and ideologies) maintains the gender structure through the functioning of caste rules and beliefs.

“The superposition of endogamy on exogamy means the creation of caste”. The unique collision of patriarchy and brahminism (upper castes rituals and ideologies) maintains the gender structure through the functioning of caste rules and beliefs.

Sharmila Rege in her articulation on the Brahmanical violence against women point out how gender remains paramount to the structuring of caste inequalities. Since its inception, the state has treated the issue of caste and gender as separate political agendas. One has to explore the significant links between caste and gender, caste and violence, caste and desire, caste and politics, caste and religion as daughter of late Dalit feminist Rajni Tilak, Jyotsna Siddharth argues to understand the nature of sexual violence carried on Dalit women bodies.

Also read: Two Young Dalit Girls Raped Mere Days Apart: A Testimony Of Caste Based Sexual Violence

You might question, how could violence have a different form and impact? We would’ve concluded violence has no variations if our facts spoke a different tale. Unfortunately, violence carries a specific character in the way it manifests itself in the lives of upper caste and lower caste women in India. Factually, the majority of upper caste women are targeted for not conforming to their caste rules and punished with honour killings, verbal abuse, widow burning, dowry blackmailing and social outcaste. On the other hand, in the case of lower caste women, the savarna male gaze is a concerning violent aspect. The rape cases of women belonging to lower castes have not reduced overtime. Infact, Dalit women are at the forefront protesting against rape, violence against lower caste men in which the savarna women play a major role as they participate and often encourage their men folk to carry out the violence publicly to shame the entire Dalit community.

In the year 1991, an estimated number of two million women were the victims of rape. Within this number, the majority of the victims belonged to Dalit and Tribal backgrounds with the crime being more gruesome in areas reserved for the army and police personnel only. Post the Emergency, autonomous civil organisations and groups organised themselves to voice the mass gangrapes of women belonging to lower castes in northern India. This explains why the second feminist wave in India characterised itself as a major force fighting violence against women.

Fostering this discussion further demands us to interrogate and examine which forms of violence have been addressed by the civil society and governments in the past. It is much known that during the pre-independence period, the colonial led administration along with the social reformers and intellectuals intervened through social legislation to bring reforms seeing the plight of the Hindu women. The social reformers either fit into the group which championed to reform Hinduism or those committed to modernising the Indian tradition. Primarily, the violence inflicted on upper caste women through rituals and beliefs such as widow burning, seclusion, child marriage, dowry, social death) marginalised lower caste women further. The new Zamindari system of land legislation heightened the sexual violence and vulnerabilties of being trafficked as “women slaves” for the lower caste women although their concerns weren’t taken in cognizance and have been absent within the debates on sexual violence since decades.

On the other hand, the politics of nationalism adequately used the category ‘Indian woman’ as a homogenous unit, focused entirely on reform catering to the upper caste, Hindu and middle class women. Here, examining the pre-existing distinctions shaping ways of life become interesting. The material/spiritual distinction transformed into categories of inner/outer, home/world. The responsibility to maintain the sanctity and spirituality of ‘home/inner’ world has been put on women, especially upper caste women as the ultimate torch bearers of Indian tradition, relegating lower caste women, the status ‘impure’ as they belong to the lower working class. Women’s movement in India is witnessing a moral dilemma as women belonging from the dominant groups are participating in violence leading to caste and communal conflicts. The politics of nationalism along the lines of caste and gender has altered the dynamics of women’s movement.

Also read: Dalit Histories: Beyond The Binary Of Atrocities And Reservation

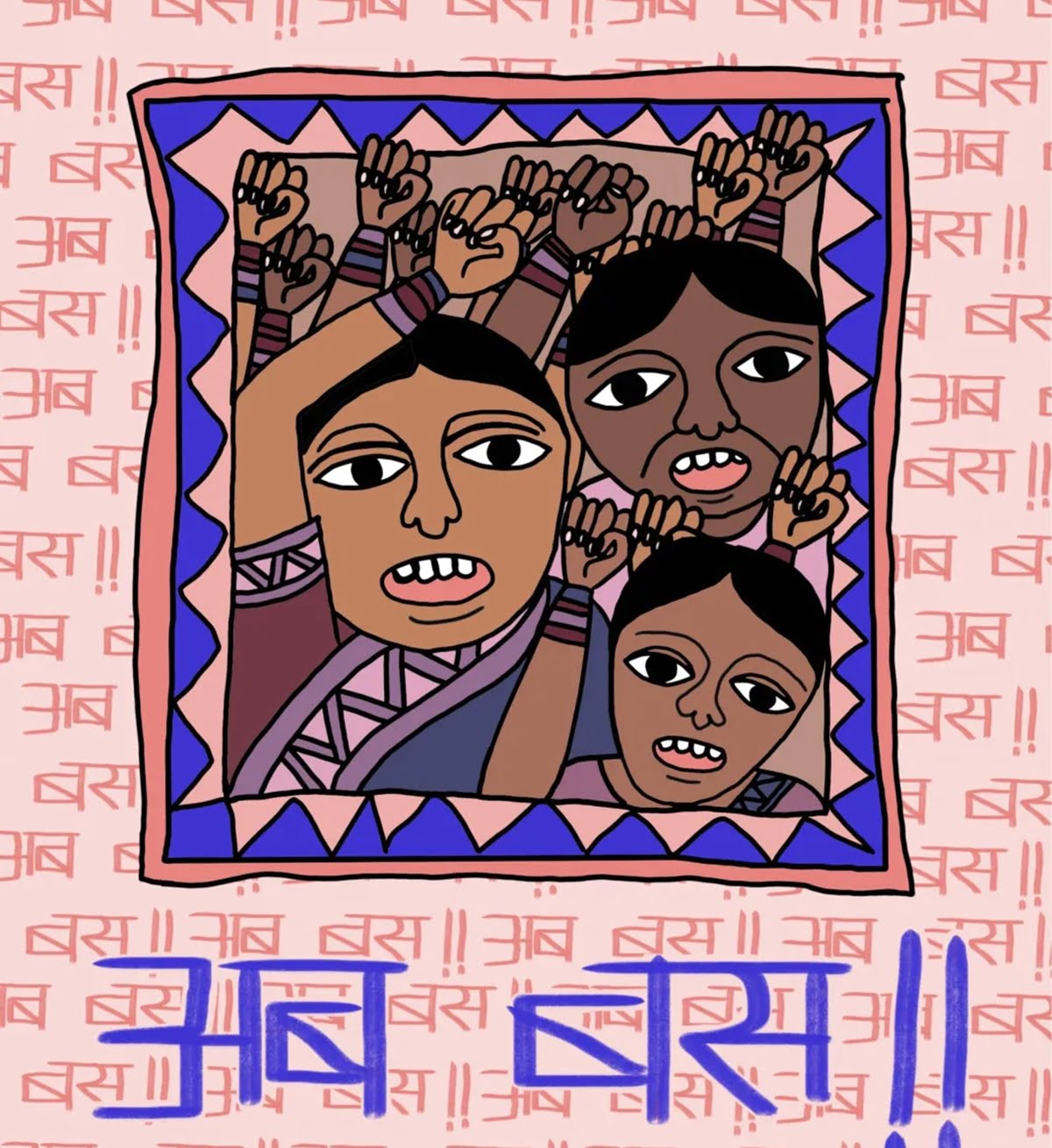

Our lives matter, Dalit women lives matter

The women’s movement has its limitations like any other movement. It is in understanding them, we can fulfil the desired outcomes. I’d like to end this piece by suggesting the way forward for the women’s movement in India to incorporate a more nuanced perspective on the linkages between caste and gender, caste and violence. Firstly, the Indian women’s movement has heavily focused on the issues of pertaining to sexual violence and gender within the urban centeres. Rural India has been neglected in much of the debates which gives us a half picture since 70% of India’s population still resides in rural areas. Secondly, concepts such as “Dalit patriarchy” are flawed as Dalit men themselves remain victims of caste confrontations and therefore, at no given point, practice patriarchy that is alien than Brahmanical Patriarchy if they do. Brahminical Patriarchy doesn’t refer to patriarchy practiced by Brahmins rather refers to Patriarchy which is embedded in caste structures. This is important as it reminds us to historically analyse alleged complaints of sexual harassment made by upper caste women against lower caste men as such complaints are the result of caste confrontations between lower and upper caste groups. Agency of upper caste women is emphasized here, however behind such alleged complaints often lies the motive to hack Dalits to an easy death. Such complaints, even when true, cannot be judged devoid of the reality of the abuse Dalit women have been facing by the upper caste men. Therefore, a loud call is needed to combine the struggle of the women’s movement with the resistance embarked by the Dalit women.

A systemic analysis, historical knowledge on the link between caste and gender, narratives about women from different socio-economic locations, letting the mike pass to the marginalised women to speak for themselves explaining their history, without forcing the flawed historical version are only baby steps in this journey of talking about sexual violence and its many forms inflicting Dalit and non-Dalit women in India today.

In an utopian world of Ravidas, a state, social evils or conflicts would not exist. Through Ravidas’s idea of Begumpura Shahar (Begumpura City), we can imagine a world that is kind although it is time that we begin to act, to find solutions to our pending conflicts. It is time we march ahead and acknowledge the gaps, the intersectional linkages which bind us, more. Do you believe it is possible to find a middle ground where we agree violence has many forms? A systemic analysis, historical knowledge on the link between caste and gender, narratives about women from different socio-economic locations, letting the mike pass to the marginalised women to speak for themselves explaining their history, without forcing the flawed historical version are only baby steps in this journey of talking about sexual violence and its many forms inflicting Dalit and non-Dalit women in India today. In the words of Maya Angelou, there is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.

About the author(s)

Shainal Verma is a feminist research scholar at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi. She is a Writing Urban India fellow and an Institute of Critical Social Inquiry New School fellow. She writes on gender, caste, visual culture, and urban space.