Posted by Gracy Andrew

As a society, we rarely talk about death, dying, or grief, especially with our children. Yet, all of us lose important people, and the experience of grief and the process of mourning are inevitable parts of our lives.

COVID-19—especially the second wave—brought death and grief onto the center stage in our country. Most people have been touched by the death of a relative, friend, or neighbour. Some have had to deal with multiple deaths, and in many cases, have not been able to see their loved ones or conduct their final rituals.

During the crisis, there is no doubt that social media was able to help people connect with each other and seek help to get access to hospital beds or oxygen. Yet, at the same time, the images of burning pyres and news about people dying due to a lack of oxygen supply—which were shared across news channels and through social media—have compounded the trauma and increased anxiety around death.

Families were devastated and there was no outlet, nor was there time and space to come to terms with any losses they might have faced. In particular, children and young people have had to navigate this with little to no support available. With schools closed, widespread economic hardships, and looming uncertainties, young people were caught unprepared. Many had to face the loss of multiple family members, severe illness, and in some cases, had to fend for themselves since the adults in their lives were either ill at home, in hospitals, or no more. For many children, the adults in their lives were dealing with their own struggles and submerged in their own grief, and were unable to fathom the impact on their children and adequately support them.

While children are often a part of these mourning rituals, it is still not common to discuss death with children.

Grief is often described as an emotional response to loss; but grief is not a simple response. It can evoke a complex amalgam of powerful emotions such as sadness, anger, guilt, or regret. These emotions can be so overwhelming that they often translate into a physiological response, such as headaches, stomach aches, changes in sleep and/or eating patterns, among others.

Also read: How Family Vlogging Invisibilizes Children’s Consent

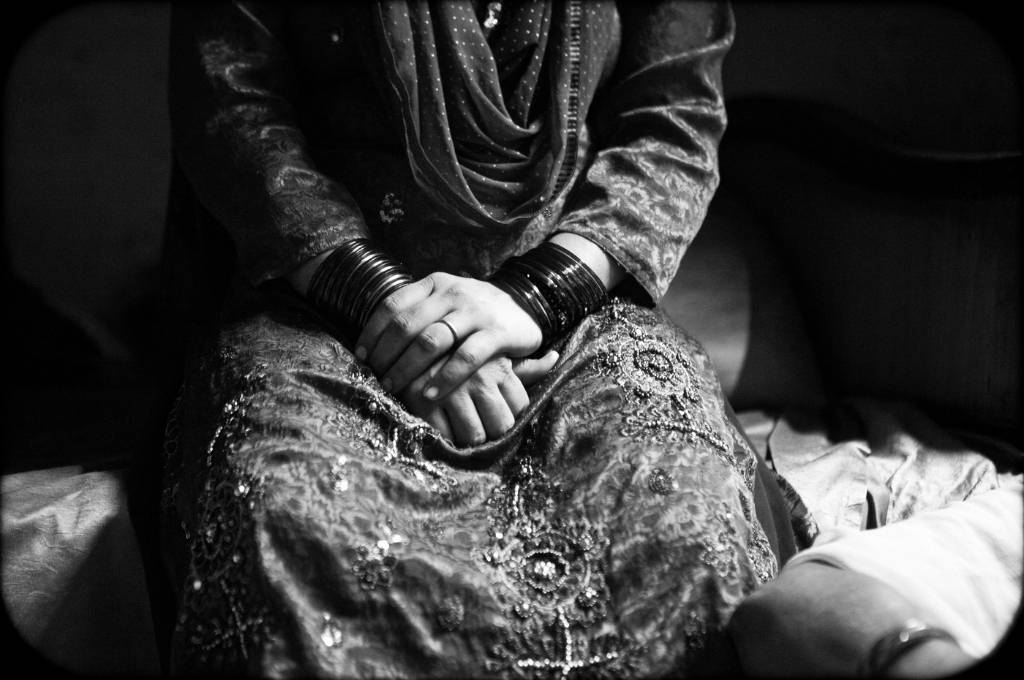

Culturally in India, each religion has its own religious practices and mourning rituals, that help aid the grieving process—many of which have been disrupted during the pandemic. While children are often a part of these rituals, it is still not common to discuss death with children. Most of the time, they tend to come to terms with death in their own way.

This situation brings to the forefront two important factors that need to be considered going forward:

Understanding how children process grief and death

Developmentally, children process death and grief differently at different ages. A five-year-old cannot comprehend concepts of a soul or afterlife and believes the dead person will come back. A seven-year-old might begin to understand that death is permanent and can develop an extreme fear of death and of other adults dying. By the time a child is nine years old, they understand the permanence of death more clearly and are very curious about death and the body, and may ask questions if given a chance.

With varying levels of understanding of death among children comes different behavioural reactions. A five-year-old may display regressive behaviours such as bed-wetting or thumb sucking. On the other hand, a nine-year-old may be riddled with guilt and blame themselves for the death, which manifests in exaggerated fears or clinging to adults in their lives. Very few adults are aware of these manifestations of distress that children exhibit. Often adults may react to aggressive behaviours displayed by the child by punishing them—not understanding that the child is simply trying to make sense of their disrupted life and the absence of a loved one. Most adults are fearful of death, and they assume that exposing children to death or having honest conversations will traumatise them.

For children, the experience of death and grief has many dimensions. It is an emotional, intellectual, as well as a spiritual experience. Emotionally they struggle with overwhelming emotions such as fear and guilt, but at the same time, they try to make sense of death. Intellectually, they try to understand the fact that their loved one is not coming back and what that means—they try to figure out where the person has gone. Since religion plays such a large role in death, the rituals and the process of laying the dead to rest makes death a spiritual experience for children. They try to find their own spiritual meaning.

Families, teachers, and health professionals could play a crucial role if they understood how to talk to children about their experiences.

It is important for adults to understand children’s responses and provide them with the space to ask questions, express their feelings, and talk about their fears. Families, teachers, and health professionals could play a crucial role if they understood how to talk to children about their experiences. Programmes in schools that equip children with social-emotional learning skills or emotional resilience skills should incorporate conversations around death and grief. Children do know more about death than we think. They see it on TV or experience it when pets die. We can talk to them about death by referring to the phenomenon as seen in nature or on TV, taking their developmental age into consideration.

Creating awareness among adults

Alongside understanding how children process grief and bereavement, it is crucial that adults—including medical professionals and mental health service providers—are equipped to have these conversations. In many high-income countries, grief and bereavement counselling are part of regular counselling training; it is not uncommon to have bereavement support services that people reach out to when they find it difficult to deal with loss.

In India and in many other countries with limited resources, bereavement counselling can be seen as a luxury and not a priority. Trainings in managing grief and bereavement are generally only a small part of certain targeted interventions. Some examples of these are psychosocial support programmes that include addressing loss during humanitarian crises. The National Institute of Disaster Management (NIDM) in collaboration with the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) has developed a training of trainers module on psychosocial care in disaster management. Similarly, the National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO) has training programmes for caregivers working with people living with HIV/AIDS, that include managing loss and bereavement. Similarly, palliative care programmes cover loss and bereavement as well.

But beyond isolated programmes, there is very little being done to respond to grief and bereavement in a systematic manner and within universal programmes.

Apart from national programmes, a number of civil society organisations provide these services as part of targeted interventions. For instance, in the aftermath of the 2006 tsunami (and the numerous disasters that have happened in recent years) many nonprofits and mental health personnel worked with children and families to deal with loss, grief, and the trauma that they were experiencing.

But beyond these isolated programmes, there is very little being done to respond to grief and bereavement in a systematic manner and within universal programmes. Grief counselling rarely features in general counselling training, such as for school counsellors. Creating awareness about grief and bereavement is rarely part of any programmes, either for the public or for specific groups such as medical professionals or teachers. Very few people are aware of how children process loss and grief. There are even fewer awareness programmes that cover grief and bereavement issues in children and adolescents or the risks of prolonged grief disorder.

Also read: Child Protection Schemes Are Failing Children Orphaned By COVID-19

Building a collective response

With the pandemic bringing issues of death and grief to the forefront, it is time we start talking about them. Moving forward, governments, civil society organisations, educational and vocational institutes, and healthcare services need to start thinking about including training on management and coping with grief. This needs to be done in programmes for counsellors, teachers, frontline workers, and other healthcare professionals.

We have all collectively faced loss and grief, and we must collectively set up mechanisms within organisations and institutions to support each other.

Maintaining well-being and coping with stress is not just an individual responsibility. It has to be part of the institutions and systems that we are part of. We have all collectively faced loss and grief, and therefore, we must collectively set up mechanisms within organisations and institutions to support each other. Group memorial services can be set up digitally, support groups can provide bereaved people spaces to express their emotions, and children and adolescents should be given opportunities to communicate their experiences through group activities (digitally or in-person when schools and institutions open).

Culturally, death, bereavement, and grief have been intensely personal, and the associated rituals and practices have been very private or shared with only family and close friends. It is time we start talking about death and grieving more openly. Most importantly, we need to start preparing our children for these experiences and providing them with the space and time to talk about death.

This piece was previously published on India Development Review and has been re-published here with consent.

Featured Image Source: Charlotte Anderson

About the author(s)

India Development Review (IDR) is India's first independent online media and knowledge platform for the development community.