Culture is not innocent. The influential sociologist Pierre Bourdieu demonstrated how culture in its embodied form as habitus restricted class mobility in French society. Habitus is our way of acting, feeling, thinking, and being, shaped by the social structures we inhabit. Whether we have an urban or rural habitus, upper-class or working-class habitus, and upper-caste or Bahujan habitus has a profound impact on our life chances.

In the first part of this series, I explored how generations of acquired privilege enabled upper-castes to make a smooth transition to a modern, capitalist society where they now constitute the status group of “educated classes”. The upper-caste habitus has accumulated all the cultural capital—good education, fluency in English, exposure, and cosmopolitanism—that is considered ‘meritorious’ and desirable in modern professional fields such as Business, Media, Academia. Cultural capital, however, is only one part of the advantage of having an upper-caste habitus. The other is knowing the unwritten rules of social conduct within this field.

The upper-caste habitus has accumulated all the cultural capital—good education, fluency in English, exposure, and cosmopolitanism—that is considered ‘meritorious’ and desirable in modern professional fields such as Business, Media, Academia. Cultural capital, however, is only one part of the advantage of having an upper-caste habitus. The other is knowing the unwritten rules of social conduct within this field.

Also read: Caste & Habitus Part I: The Role Of Cultural Capital In Perpetuating Caste Hegemony

Going in for the interview, upper-caste candidates know what kind of clothes to dress in and how to groom themselves. They are accustomed to being in similar social settings and don’t feel out of place in the environment of a corporate office.

Meanwhile, Bahujan candidates are self-conscious and inhibited, like fish out of water. The formal clothes and shoes, perhaps borrowed from friends, feel like a put-on. Conversing in English is intimidating and they are unsure of how to behave in this alien environment.

Bourdieu explained this phenomenon in sociological terms as ‘hysteresis’, arising from a mismatch between the habitus and field. Say, you grew up in a farming family in a small town. You dress in dhotis, know the nuances of cultivation, and are adept at diffusing disputes with middlemen at the mandi. You have what Bourdieu termed a “feel for the game”. But, if you were to find yourself in the middle of an agriculture conference, hosted in a five-star hotel, you would feel out of place and your attire and mannerisms looked down upon. Your habitus does not match the field. Conversely, an academic from the conference, dressed in a suit, would not fit in at the mandi. However, unlike the farmer in a five-star hotel, her cultural capital would still command social prestige.

In any society, the culture of the dominant, ruling class is considered legitimate. Knowledge of Sanskrit and Vedas is respectable so even state-run schools will have slokas for morning prayers but never the Anaadi Prarthna, a prayer song of the Sarna faith. Non-vegetarian food is considered ‘impure’ so schools and workplaces often try to impose vegetarianism.

Likewise, upper-class culture is also exemplified. In the name of ‘personality development’, finishing schools thriving in our cities teach young men and women the ways of the upper-class—how to shake hands, how to dress in formals, how to eat in a fine-dining restaurant. In this social reality, when you belong to the dominant group, you can simply ‘be yourself’ but the dominated have to remake their habitus to fit in.

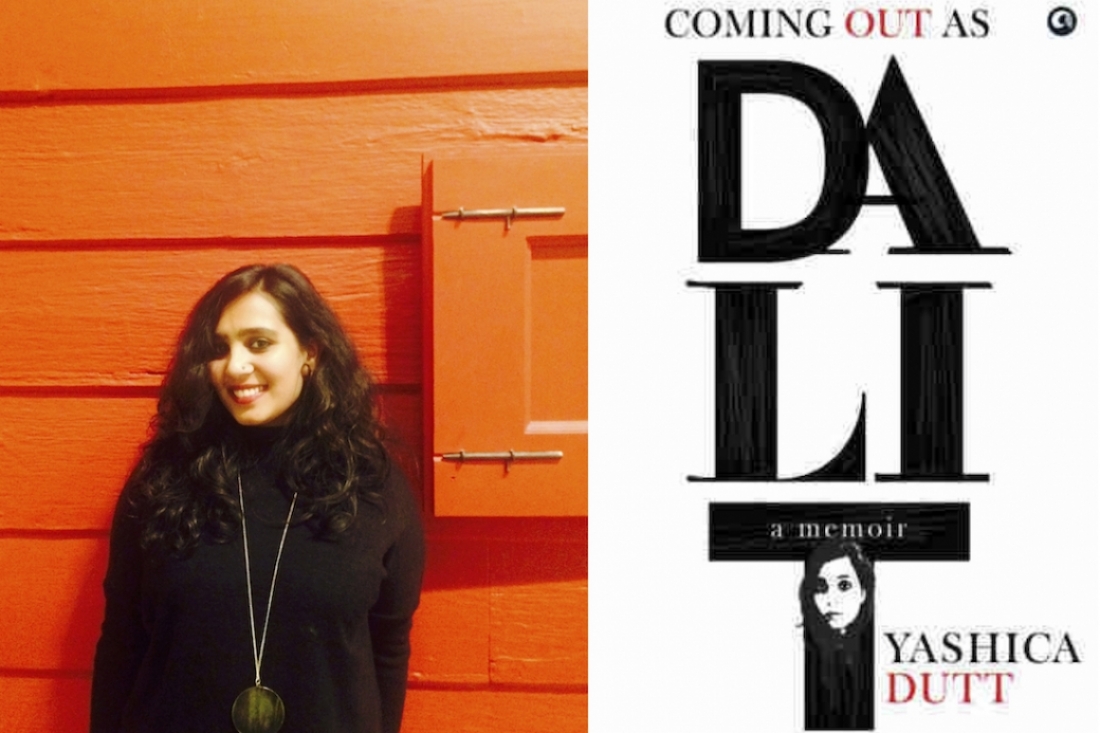

In her book Coming out as Dalit, journalist Yashica Dutt described her mother’s resolute attempts to craft an upper-caste habitus to hide their Dalit identity. She made sure Yashica and her siblings dressed well, attended good English-medium schools, had birthday parties and movie nights, pawning off her jewelry, and doing multiple jobs to keep up this facade. When sending Yashica off to a boarding school, her mother bought her gold studs, high-quality buckets and mugs, and novelty shoes to help her fit in.

Yashica writes, “Living with upper-caste girls was meant to train me to be like them. By picking up little details like how they spoke, braided their hair or tucked in their sheets—some of the markers of upper-caste culture—I would successfully blend in with them for the rest of my life.” Bahujans feel compelled to take such measures because not blending in could mean alienation.

When journalist Tejas Harad surveyed the few Bahujans in English media, one of the respondents said, “The feeling of alienation is what haunts me the most. Because most journalists are urbanites, they willy-nilly pass judgments, maybe unknowingly, for not knowing or having experienced what they consider in trend or necessary.”

The respondents spoke about their challenges integrating into the culture of newsrooms dominated by the upper-caste. Vegetarian-only policy in the canteens, either explicit or implied, forced Bahujans to give up non-veg or risk censure. Casual social interactions at the workplace are crucial to securing career opportunities but Bahujans found them hard to engage in because of language constraints and unfamiliar conversation topics. “Being a first-generation English learner, my confidence level was extremely low because of which I worked under constant fear of facing humiliation…I had to put in four times the effort when compared to journalists from privileged backgrounds to do my work,” one of the respondents said.

Such hysteresis, or habitus-field mismatch, causes deep psychological distress, anxiety, and feelings of inferiority. You realize that you are not ‘good enough’ as you are for your new environment and you have to work extra hard to ‘develop’ your personality.

As a backward-caste teenager in largely upper-caste classrooms, my experience of hysteresis had been overwhelming. A job in the Gulf meant that my father could send me to an expensive college to study journalism but I didn’t have the cultural capital to match my peers. Among classmates who came from highly-educated families, had travelled the world, and had been exposed to a variety of ideas and experiences, I felt intimidated and inferior. My habitus had developed in a small world, in a conservative Shudra community in a Kerala village, among family members who were drivers, electricians, and farmers. I was too scared to participate in class or events because I thought everyone was better than me.

The hysteresis eroded my self-confidence and it persisted until I could remake my habitus by switching from salwars to Western outfits, catching up on pop culture, and adopting the lifestyle of my classmates. Among other things, such a transformation was possible for me because I had economic capital. Not everyone is as fortunate. I also had the ‘privilege’ of belonging to a caste that was not the most oppressed. Had I been Dalit, the added stigma of caste bias would have intensified the hysteresis.

Also read: The Argument Of Meritocracy Is Inherently Flawed. It Is Time We Put It To Rest

Using the sociological toolkit of habitus, capital, and field, Bourdieu revealed how social hierarchy is maintained and reproduced not so much through physical force but domination through the means of symbolic capital. For a Bahujan to make it to senior positions in a corporate office, newsroom, or university, she would have to be born into a well-educated family, preferably in a city, or have the means to attend schools and colleges where she can acquire the right habitus and cultural capital.

The specter of caste takes many forms and although fighting explicit caste-based discrimination and violence remains our primary challenge, we must also acknowledge the subtle, invisible role that culture plays in preserving upper-caste hegemony.

Statistically, far fewer such individuals exist among Bahujan communities than among historically advantaged upper-caste groups. The specter of caste takes many forms and although fighting explicit caste-based discrimination and violence remains our primary challenge, we must also acknowledge the subtle, invisible role that culture plays in preserving upper-caste hegemony.

Meghana Choukkar is a journalist and postgraduate student at King’s College London, where she is learning to unravel the complexities of Indian Politics and Society. You can find her on Twitter.

Featured image source: Scroll.in

It is Natural Birdsmof Same feather come together.

Even among human society People of Perticular instincts or of Comman Interest Come together to meet their needs mutually.

That is how CASTISM has developed in The World. Gradually THESE GROUPS make them watertight compartments of their own Castes or Communities , to become Religious Beliefs and Practices . Later ??? It went so much UNCONTROLLED TO HAVE FIGHTS AMONG THE RELIGIOUS GROUPS OR GROUNDS.

We’re as NO RELIGION PREACHES TO TROUBLE OTHERS/RELIGIOUS GROUPS . But !!! We know what is happening in The World Always. THIS IS THE TRUTH ABOUT RELIGIOUS PRACTICES in brief .

Some Decades Back Western Women STARTED WOMEN LIB Movement to Liberate The

Women from what ? I don’t know. As Time Passes It Gradually WITHERED AWAY .

There is NO DOUBT WOMENFOLK DO HAVE MANY VARIETIES OF PROBLEMS IN THE WORLD.

Until & Unless we START BEHVING LIKE HUMAN BEINGS , The Sufferings in Human Society CAN NOT BE MINIMIZED .

The place here is too small to Explain all these aspects of life in detail or to elaborate now.

As I mentioned earlier in my previous comment , a leasurly meeting can help me to give a detailed explanation of the subject under our question now.

With Best Wishes For Betterment Always ,

SHIVA KUMAR.T.N.