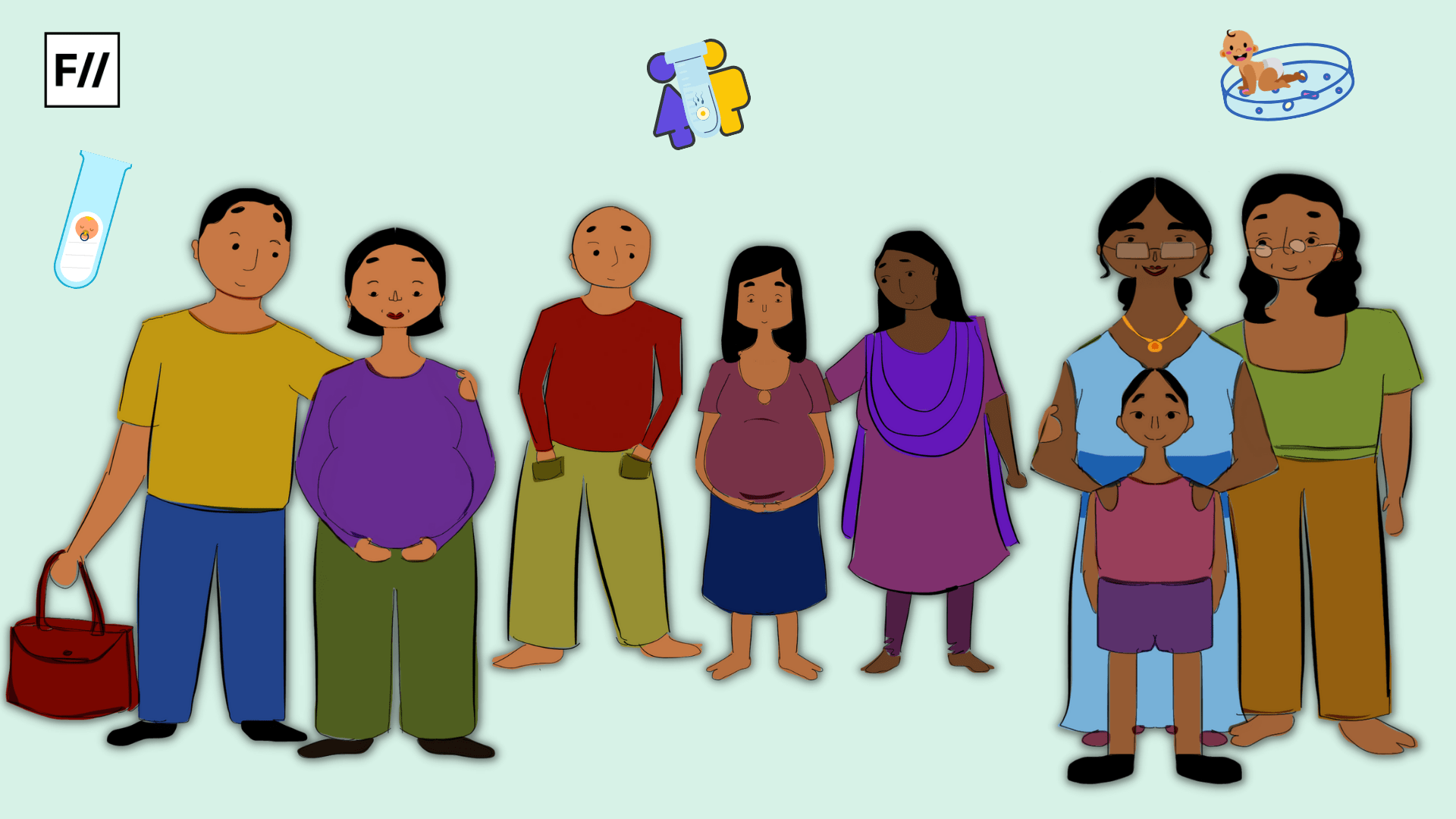

Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for September, 2021 is Parenthood. We invite submissions on the many layers of being parents, having parents and navigating the social norms of parenting throughout the month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

Infertility in general refers to an individual’s or a couple’s inability to conceive despite cohabitation and exposure to pregnancy. As a result, if a couple is unable to conceive after about a year of trying, they are considered infertile. There are two types of infertility: primary and secondary.

When a couple is unable to conceive, this is referred to as primary infertility. On the other hand, secondary infertility means that after the first pregnancy the couple has not been able to conceive anymore. But with the emergence of artificial reproductive technologies, the perception towards infertility and biological relationships are changing.

These artificial reproductive technologies are denaturalising and blurring the boundaries between nature and culture. As the very idea of kinship is perceived to be rooted in notions of biological reproduction, artificial methods question and reinterpret the notion of biological parenthood.

Artificial reproductive technologies have changed the notion of ‘relatedness’ and have given a more dynamic meaning to the institution of kinship and family. Rather than treating kinship as a naturally occurring phenomenon as it popularly is, these technologies reimagine them as a social construct.

Hence, artificial reproductive technologies deconstruct the age-old perception of kinship and bring in a certain ambiguity to the kinship relations. For example, one hand, in the case of sperm donors, a secretive space is created as most of the sperm donors prefer to remain anonymous. On the other hand, egg donation creates female alliances among the female individuals engaging in the process.

Gestational surrogacy blurs the differentiation between biological and social motherhood. In case of surrogacy, the biological contribution of the father is uncontested, whereas the relationship of the mothers with the fetus is a complex one. Though much research has been conducted on the role of women in surrogacy or negotiating infertility, little research has been done on the anthropological discourse on the position of the father while undergoing these artificial arrangements

Anindita Majumdar, in her paper titled The Rhetoric of Choice: The Feminist Debates on Reproductive Choice in the Commercial Surrogacy Arrangement in India states that it is important to go beyond the binary of passive victim and active agents as the discourse of choice implies a much more nuanced understanding. The act of surrogacy according to the author, deconstructs the sacrosanct construction of ‘motherhood’ by redefining it by incorporating both values of intimacy as well as market.

Gestational surrogacy blurs the differentiation between biological and social motherhood. In case of surrogacy, the biological contribution of the father is uncontested, whereas the relationship of the mothers with the fetus is a complex one. Though much research has been conducted on the role of women in surrogacy or negotiating infertility, little research has been done on the anthropological discourse on the position of the father while undergoing these artificial arrangements.

The introduction of technologies like sperm donorship have challenged the traditional role of fatherhood as well. The role of the male partner of the surrogate is considered to be an important one in the arrangement which has not been paid enough heed to . Being a partner to the surrogate mother, it is assumed that the male partner also qualifies as a ‘father’ and hence leads to contested notions of fatherhood.

The relationship between the new born and the surrogate mother is a complex one as there seems to be a forced disconnect initiated by medical industries between the two. Feminist scholars view the surrogate as a ‘mother’ instead of a reproductive apparatus and emphasise on the connection between the child and the surrogate mother.

Also read: Surrogacy Regulation Bill 2019: Altruism Or State Control Of Bodily Autonomy?

Artificial reproductive technologies are a symbol of our changing times, representing the growing importance of biotechnologies in the formation of individual, familial, and collective identities. They are initiating transformations in a wide range of cultural domains and reimagining the idea of parenthood. This reimagination helps in perceiving parenthood in a more fluid manner, going beyond proprietary, biological, deterministic views

The introduction of artificial reproductive technologies consisting of options like fertilisation in vitro, gamete donation and surrogacy unfold new possibilities of kinship challenging the biological assumption of the same. In the case of gestational surrogacy, the process presents three possibilities of motherhood – the biological mother, the gestational mother and the social mother respectively.

In an ethnographic study in Anand, Delhi, it is cited that most surrogates who are the gestational mothers, consider their ties with the child to be more than the genetic mother as they share substances like blood and breast milk with the child. Also the effort of the gestational mother at the time of pregnancy triumphs, according to them the genetic tie between a mother and a child.

Surrogacy challenges the popular ide that ‘the child is product of the father’s seed’ by emphasising more on the sweat and blood of the gestational mother during the process of pregnancy and considers the child to be a product of the same.

Artificial reproductive technologies are a symbol of our changing times, representing the growing importance of biotechnologies in the formation of individual, familial, and collective identities. They are initiating transformations in a wide range of cultural domains and reimagining the idea of parenthood. This reimagination helps in perceiving parenthood in a more fluid manner, going beyond proprietary, biological, deterministic views.

Also read: Generation Gap: The Conflicts And Occasional Joys Of Negotiating Space With The Elderly

Featured Image Source: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Brishti Sen Banerjee is a PhD Research Scholar in Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur. She has experience in formulating research tools, conducting on ground research work and in advocacy. She is a passionate lover of junk food and loves the mountains.