Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for September, 2021 is Parenthood. We invite submissions on the many layers of being parents, having parents and navigating the social norms of parenting throughout the month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

Hindi cinema, particularly Bollywood, has left no stone unturned in its efforts to percolate the constructed ideas of true ‘Indian-ness‘ through movies. The ideals of being an ‘Indian true to values‘ include respecting elders, being committed to family, adhering to pre-constructed gendered norms, abstaining from alcohol and smoking, and being patriarchy approved in behaviour.

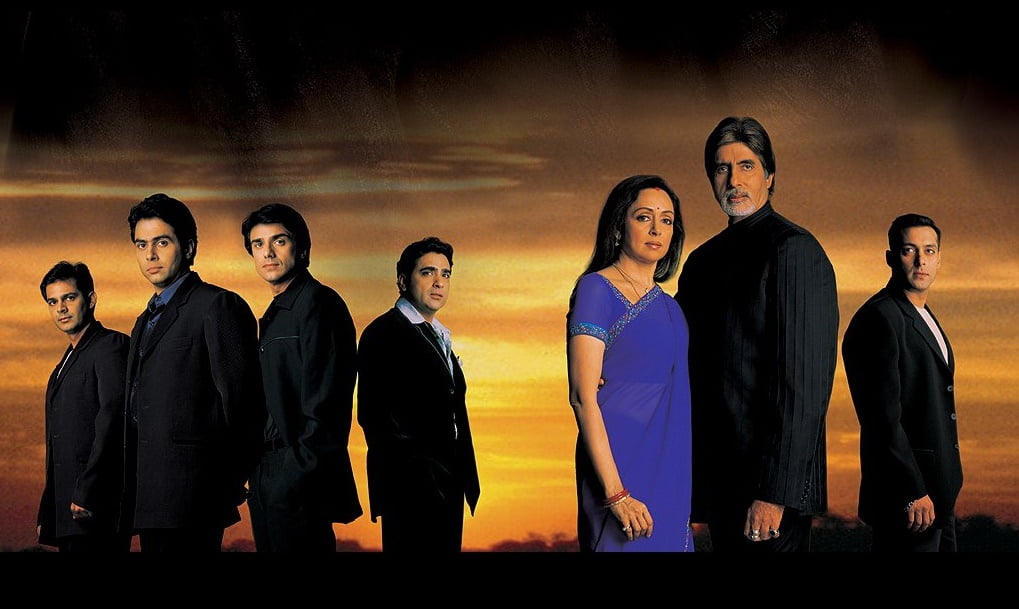

Baghban, a Hindi film relased in 2003, directed by Ravi Chopra, depicts all these constructed values through the lens of parenting. When it was released, the film was a box office success. Baghban’s plot is based on the lives of an aging couple played by Amitabh Bachchan and Hema Malini, and their four sons.

The sons live in different cities with their working wives and gather occasionally during festivals at their parents’ residence. Amitabh Bachchan’s retirement age nears and he does not have huge savings, except for the amount he receives as pension. The sons then decide to take each of their parents individually to their respective homes and ask them to live with each of their sons for six months. Both the parents heartbreakingly agree and move into different cities with their sons.

Blame it on the daughter-in-law

As the story progresses, we witness various instances where we are forced to question why the daughter-in-law’s character is portrayed as evil. When Hema Malini shifts in with her son, she experiences a more urban lifestyle along with his family, which she is not used to.

The movie tries to reinforce the stereotypical idea that daughter-in-laws are evil individuals who brainwash their husbands and bring shame to the family. Hema Malini conveniently blames everything on her daughter-in-law. Living in the 21st century, we have been striving hard to normalise the idea that working women are not bad mothers or wives just because they give priority to their professional pursuits.

They are entitled to their individuality and agency. Nevertheless, Baghban depicts the contrary. It fortifies the notion that working women are not capable of inculcating good values in children, totally ignoring the role of fathers in parenting. The film also positions the wife of the couple’s adopted son Alok, as an ideal woman, who embodies patriarchal morality to showcase how women must always only choose family and let go of their personalities.

There is absolutely no bar to respecting ones parents or expressing one’s respect for them through gestures of one’s choice. But Baghban reiterates the idea that without following these ideals, you are not worthy enough to be called a good offspring. The obsession with sanskaar pushes one to compromise their own identity and beliefs. If one does not adhere to such extremely proprietary notions of parenthood, the conclusion is the same as Paresh Rawal’s dialogue to his wife in the film – ‘aulaad aisi hoti hai to acha hai hume koi aulaad nahi hai’

The film conveys a message that children are expected to uproot their professional pursuits and their private lives, and live life according to their parents’ desire. To be an ‘adarsh’ beta and bahu, you have to abide by the constructed roles of gender and submit to the proprietary notions of parenthood, which are based on control and domination by parents over children.

This is brought out through the character of the adopted son, played by Salman Khan. He worships his adoptive parents, places their photograph in his private prayer room at home, and wins their hearts. The couple disown their biological sons and make the adopted son their legal heir.

Also read: Moulding Girls To Be Future Mothers: Assertion Of Gender Roles Through Parenting

There is a scene in Baghban where Hema Malini tries to teach her son how to control his wife and daughter, and warns him to ‘keep an eye‘ on their activities. Her son responds that he is not in the position to control anyone’s life. Hema Malini tells him that for women, times are always the same and that it is women who must be careful to not be exploited. The film wants its audience to take this parental message seriously.

Identity, agency and parenting

The film promotes the character of Alok the adopted son, and his wife Arpita to be the ‘ideal beta and bahu‘ every family should have. The instances where he touches the feet of his parents in charan sparsh, sleeps at their feet, and worships their photograph in his prayer room are all glorified and pedestalised in Baghban.

There is absolutely no bar to respecting ones parents or expressing one’s respect for them through gestures of one’s choice. But Baghban reiterates the idea that without following these ideals, you are not worthy enough to be called a good offspring. The obsession with sanskaar pushes one to compromise their own identity and beliefs. If one does not adhere to such extremely proprietary notions of parenthood, the conclusion is the same as Paresh Rawal’s dialogue to his wife in the film – ‘aulaad aisi hoti hai to acha hai hume koi aulaad nahi hai’.

The film makes the characters who exercise their freedom to live life on their own terms look guilty and evil. It feeds onto the patriarchal, anti-female power structures within families, and in a certain instance, also justifies victim blaming when a woman complains of sexual assault.

There is a scene where Hema Malini follows her granddaughter to a pub where she meets her boyfriend. However, the boyfriend does something that the is not comfortable with, and Malini steps in to save the day. The way this scene is staged is highly questionable. The girl is blamed for the assault on her, normalising the archaic idea that if you are a woman who attends parties and/or has boyfriends, you ‘asked’ for it.

Parenting is not about power tactics or domination through emotional control. Parent-child relationships must be based on mutual respect and establishing healthy boundaries, allowing everyone to thrive and become their own individuals. Baghban sure was made at a time when these conversations were rare. But the success of the film shows how these problematic ideals are accepted by the society

Baghban puts forth the problematic parenting ideal that in order to prove your love for your parents, or to be worthy of their love, you must be subserviently sacrifice your individual identity. It positions parents as individuals who cannot be questioned or flawed. This proprietary idea of parenting is regressive and limiting.

Parenting is not about power tactics or domination through emotional control. Parent-child relationships must be based on mutual respect and establishing healthy boundaries, allowing everyone to thrive and become their own individuals. Baghban sure was made at a time when these conversations were rare. But the success of the film shows how these problematic ideals are accepted by the society. Therefore, we must constantly interrogate films like these and create conversations that underline what is wrong with their sensibilities.

Also read: ‘Shakuntala Devi’ And The Patriarchal Trope Of The ‘Good Mother’

Featured Image Source: Mirchi Play

About the author(s)

Dimple has a keen interest in history, cinema, and cultural studies, which fuels her curiosity. With an exploratory attitude towards life, she enjoys engaging in thoughtful conversations over a warm cup of tea.

Absolutely correct analysis. I could not relate to this box office hit ever and its success speaks volumes about how the society thought 20 years back. I do see the change coming in but we still have a long way to go.

Yes this film is of old time when we not had internet. Even today elder supremacy is not even Indian it’s Asian culture.

I find that parents have to prove their worthiness more to their children now than twenty years ago. Parents are judged by their own children .It’s a problematic attitude of millennials which most parents are tackling day in and out.

This article is so brilliantly written, I wish I could personally write to the author to thank for her for it.

This movie shows children splitting their parents for their convenience. They have no right to break two souls. Instead they could have dropped them in any old age home.Movie is absolutely right. The person who written this review didn’t understand the movie at all.

The article is well written and thought-provoking. Baghban showcases parenting as a domination exercising tool, and this article is a good analysis on it.