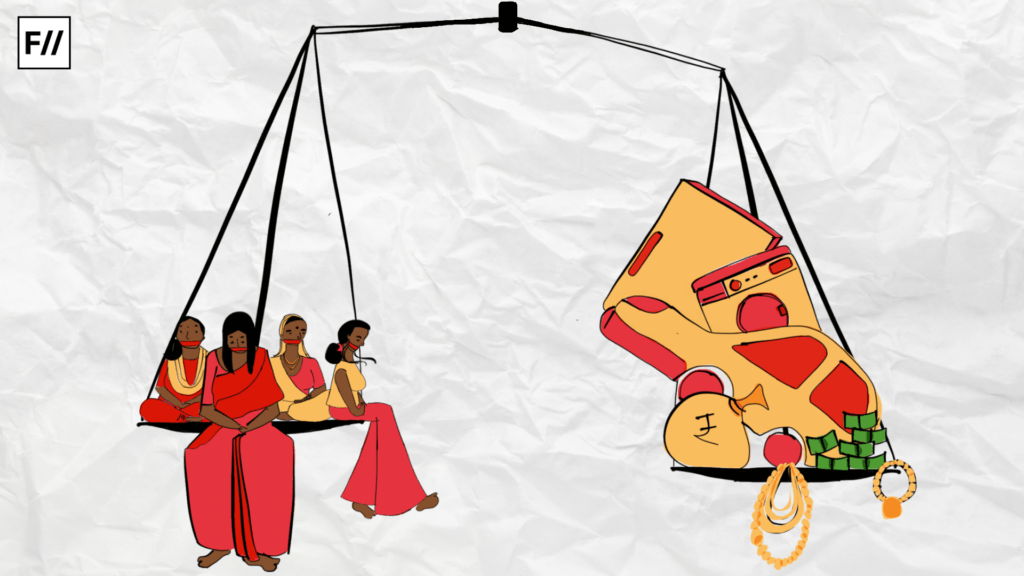

Dowry is the money, goods, or the estate that the bride’s family gives to the groom’s family at the time of the wedding. This practice is common in cultures that are strongly patrilineal, patrilocal and have male-biased inheritance laws. Historically, dowry was paid in Europe, South Asia, and Africa. In the present day, dowry is paid in over eighty percent of marriages in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan.

These days, the word ‘gift’ is sometimes used as an euphemism instead of ‘dowry’. Families that like to pose as progressive might use the word ‘gift’ to disassociate themselves from the act of giving or receiving dowry. However, even when dressed up in the polite and fancy term of a “gift”, it still remains dowry, something which is illegal.

Dowry is also most often defined and perceived as a payment made at the time of the marriage. But it is worth noting that there is a continuous nature to the payment of dowry which is often ignored. The cash and goods paid do not stop at one event i.e. the marriage. Mostly, the bride’s family is expected to make recurring payments through the life of the couple’s alliance on festivals, special occasions like birth of a son, etc. These payments are made because they are the norm and non-payment of these payments can warrant humiliation and harassment of the bride in the groom’s family. The recurring nature of dowry is still not an extensive part of academic literature and research. It continues to be restricted to the payment made at the time of the marriage only.

Families that like to pose as progressive might use the word ‘gift’ to disassociate themselves from the act of receiving dowry. However even when dressed up in the polite and fancy term of a “gift”, it still remains dowry, something which is illegal.

The practice of dowry was proscribed in India in 1961. But even more than half a century after the ban, an Indian woman becomes a victim of dowry death roughly every one hour as per the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) 2019 data.

The payment of dowry is not only still prevalent sixty years after being outlawed but it is also on a disturbing upward trend in many Indian States.

This leads us to the question—Why are dowries not only widespread but also rising after being outlawed sixty years ago? This essay attempts to answer this question.

In every culture, parents’ concern for their daughter’s marriage plays a critical role in determining gender relations.

In China, families used to bind the feet of their daughters in order to find them a good husband. Women with bound feet were believed to develop strong muscles in their hips, thighs, and buttocks and these characteristics were considered physically attractive to Chinese men in that era.

Also read: The Historical Journey Of Anti-Dowry Laws

Female genital mutilation is practiced in African countries and in some Indian communities to ensure premarital virginity and marital fidelity. It is believed to enhance women’s desirability to men and improve their marriage prospects.

In India, a marriage continues to be the ultimate goal notwithstanding academic or professional achievements. A woman choosing to not marry or marry late would most likely be disparaged and ostracized. Since marriage is so important in the Indian society and even more so for women, parents are always engrossed in finding a “good groom” for their daughters and are also willing to pay large dowries to secure the said “good groom”.

In the Indian marriage market the groom occupies a dominant position. Dowries continue to be demanded and the bride’s parents have no option but to try to meet the demands.

Wealthy households disguise a criminal offence—the act of giving and receiving dowry by opulent weddings and ugly displays of riches. On the contrary, women from middle-class and poor households continue to be harassed, humiliated, assaulted and killed for not meeting the dowry demands.

This begs the question—How to break the dowry demand?

As societies develop and men gain education, they begin wanting educated wives. In this scenario, parents can shift the resources that they have allocated for the payment of dowry towards their daughter’s education. Dowry can become the opportunity cost of the daughter’s education.

A study Preferences and Beliefs in the Marriage Market for Young Brides indicates that in Rajasthan, parents want to defer a daughter’s marriage until she is eighteen years old, but not beyond. They believe the chance of receiving a good marriage proposal increases strongly with a daughter’s education but declines quickly with her age on leaving school.

If the demand for female labor force increases, men may be more interested in marrying women who work as that can increase family’s total income and become less inclined to dowries but the female labor force participation has been on a steady decline since 2005.

Parents believe the chance of receiving a good marriage proposal increases strongly with a daughter’s education but declines quickly with her age on leaving school.

Even though some educated men have begun wanting educated wives this has not led to a fall in the payment of dowries. This means it is not only men’s preferences responsible for the continuation of dowry payments.

In India, marriage decisions are largely taken by the family of the bride. The families look for a groom from within the same religion, the same caste and also from the same economic status. A marriage outside of caste and religion is very rare and unpopular. Matrimonial apps catering to specific religions and castes have also infiltrated modern dating.

As per the 2012, India Human Development Survey (IHDS), seventy three percent of women surveyed reported that their parents or relatives alone chose their husbands. As per the recent survey from the Pew Research Center, most Indians see their country as religiously tolerant but are against interfaith marriages. Majorities of Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Jains also consider stopping inter-caste marriage of both men and women a high priority

In Europe, modernisation led to the weakening of kinship. Women could marry whoever they wished to. But in India despite development, kinship remains strong because of the prevalence of caste system. With communal disharmony, religious intolerance, fundamentalism and violence on a high, women are manacled and coerced to marry within the fetters of religion, caste and social groups.

As per the 2012, India Human Development Survey (IHDS), seventy three percent of women surveyed reported that their parents or relatives alone chose their husbands.

If a woman can marry any wealthy man, then the power of men in the marriage market would weaken. But since the woman has to marry only from within her caste and religion in India, the power gets concentrated in the hands of men.

Men enjoy monopsony power in the Indian marriage market because of endogamy. In the Indian marriage market there are only men—a single buyer that sets prices in the form of dowry and controls the marriage market.

Siwan Anderson in one of his papers showed that in caste based societies, the increases in wealth distribution that follow modernisation automatically lead to inflation in dowry payments, whereas in non-caste-based societies, increased wealth distribution has no effect on dowry payments and rising average wealth causes the payments to decline.

In present day India, an end to endogamy is a challenging task. With divisive and hateful politics, the government is not only strengthening and endorsing endogamy but also making the country unsafe for people choosing to love and marry outside the confines of religion and caste. Bigotry has been legalized through anti-love jihad laws and the onslaught on women’s agency continues.

Also read: What The Case Of Vismaya & Surging ‘Dowry Deaths’ In Kerala Tell Us

Featured Image: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism in India

About the author(s)

Shreya is a writer. Issues of how gender affects the economy deeply concern her. She likes to understand the economy, policy, theory, and the world around her with the perspective of gender. When she is not busy contemplating ideas to dismantle gender disparity she can be found cycling or studying finance.