Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for October, 2021 is Navigating Complex Emotions. FII invites submissions on dissecting the many layers of various emotions in personal and public life throughout this month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

In an article published by The New York Times, Leslie Jamison discuses women’s internalisation of socially enforced prohibitions on the expression of anger. She writes that sadness “[is] a more natural emotion for me than anger” because sadness bottles up pain inside the person while the “blunt-force trauma” of anger demands interpersonal negotiation. Her perception of sadness as a “more refined and also more selfless” feeling is not uncommon among women.

Women continue to feel apologetic for their behaviour even when their anger is legitimate. For instance, a 2008 study by Brescoll and Uhlmann exhibits that evaluators tend to assign lower status to angry women in the workplace than they do to their male counterparts. In fact, men’s anger and, in general, behaviour attain social sanction by popular insistence on phrases such as ‘men will be men.’ The normalisation of such attitudes is perhaps another reason why women feel guilty for expressing their emotions and expecting accommodating changes from men.

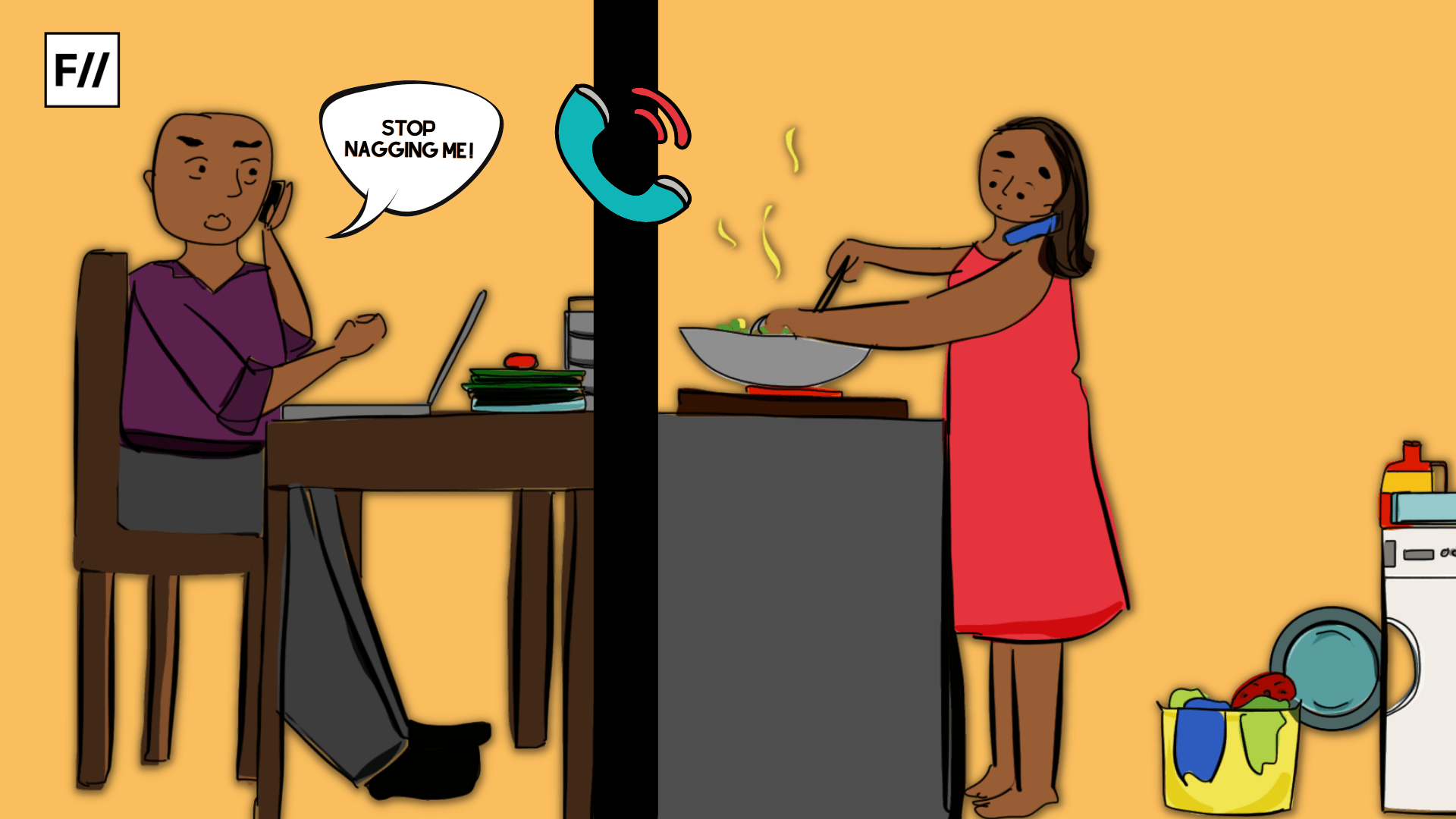

When women continue to express their complaints or concerns, they get associated with labels such as ‘nagging,’ particularly in the patrilocal households of South Asia. The trope of nagging wives in heterosexual marriages constantly remains in fashion, thanks to caricatures visible across Hindi cinema and WhatsApp forwards. Literature, too, continues to colour popular perceptions with characters and plots grounded in patriarchal indoctrination.

Ankhon Dekhi, a thought-provoking film with deeply philosophical undertones, features the quintessential nagging wife, played by Seema Pahwa. Her perennial sarcasm often serves to puncture her husband’s meditations on philosophical thoughts. In remaining oblivious to the apparent significance of her self-absorbed husband’s ideas, she gets excluded from the intellectual terrains of cognition that her husband inhabits.

The imaginary power exercised by nagging wives creates and sustains the myth of gynocentric domination in heterosexual relationships, especially in popular films such as Pyaar Ka Punchnama. The film places on women the onus of unsatisfactory romantic relationships and constructs them as hindrances in men’s personal and professional lives. Kartik Aaryan, who plays the role of Rajat, delivers a monologue that has become particularly famous in millennial and postmillennial circles.

Such films reveal how anxieties against women’s ‘nagging‘ are efforts to contain women’s emotional responses and regulate relationships within patriarchal paradigms. Messages forwarded on WhatsApp exist in addition to commercial films to maintain and perpetuate common stereotypes beyond spatial and temporal constraints: they serve as textual indicators of our cultural obsession with the patriarchal governance of women’s behaviour. Together, they sustain the myth of women’s dominance in heterosexual marriages

In characterising women as fundamentally nagging, Rajat demonises women’s expressions of anger and dissatisfaction. He begins with the declaration that his girlfriend ‘wants’ him to suffer, implying that women’s desires materialise only when they culminate in men’s hardship.

In addition, he refutes the existence of happy women, exclusively frames consumerism as women’s vice, and renders women illogical. Rajat insists that women’s nagging continues even when they are not menstruating: this universalisation of women’s behaviour posits gender as a biological construct and confers on women’s behaviour the common problem of unreasonable and irrational arguments.

The film’s sequel, Pyaar Ka Punchnama 2, features a similar monologue delivered by Anshul, whose role is also played by Aaryan. Anshul laments that while women’s clothing suggestions to men are deemed acceptable, similar recommendations by men provoke in women a feminist response, which, according to him, is necessarily inimical to a relationship.

In labelling women’s refutation of men’s advice as feminist, Anshul appropriates the popular feminist discourse and trivialises women’s opposition to social demands. He ends his monologue with the proposal that men should marry their hands instead of women, thereby reducing women to sexual partners and, in turn, relationships to sex.

Such films reveal how anxieties against women’s ‘nagging‘ are efforts to contain women’s emotional responses and regulate relationships within patriarchal paradigms. Messages forwarded on WhatsApp exist in addition to commercial films to maintain and perpetuate common stereotypes beyond spatial and temporal constraints: they serve as textual indicators of our cultural obsession with the patriarchal governance of women’s behaviour. Together, they sustain the myth of women’s dominance in heterosexual marriages.

Also read: We Need More Angry Women In Fiction: ‘Female’ Rage And Her Inner Worlds

Consider the number of domestic violence cases in India, both reported and unreported. In addition to the threat of violence and backlash, married women often negotiate with professional as well as domestic work. That they rarely afford the luxury of leisure exhibits the extent to which they remain trapped in seemingly equitable marital institutions.

Additionally, challenges posed by social pressure are quite potent for women whose identities are marked by intersectionalities such as caste, disability, class, etc. In what universe is women’s ‘dominance’ oppressing the collectivity of men?

Nagging, then, becomes a mode to channelise the frustration that accompanies their required adherence to patriarchal structures. The popular critique of nagging women, particularly nagging wives, is consequently a mechanism to suppress the expression of women’s justified anger, delegitimise their resistance to unequal division of labour, and maintain their oppression through socially sanctioned norms

Many acclaimed novels similarly feature the trope of nagging wives. Anita Desai’s In Custody, for instance, projects Imtiaz Begum as a dominating second wife of the eminent Urdu poet Nur. In one of the initial chapters, her husband gets up and leaves in the middle of her poetry performance. In the novel’s end, an ardent follower of her husband’s literary work refuses to even consider her manuscript for publication.

The criticism of Imtiaz Begum’s poetry, premised on discourses surrounding plagiarism and imitation, remains unwarranted throughout the novel. Desai’s narrative fails to acknowledge Imtiaz Begum as a poet, even though it is her investment in regular performances that financially sustains the entire household. Unfortunately, she is always viewed as either a former prostitute or the nagging wife of an acclaimed poet.

As we discuss nagging women, let’s also consider why women are sometimes forced to nag their partners. A video posted by The Swaddle suggests that women are compelled to repeatedly ask their partners for support in domestic work since they are not offered any in the first place.

Nagging, then, becomes a mode to channelise the frustration that accompanies their required adherence to patriarchal structures. The popular critique of nagging women, particularly nagging wives, is consequently a mechanism to suppress the expression of women’s justified anger, delegitimise their resistance to unequal division of labour, and maintain their oppression through socially sanctioned norms.

Also read: Sharp Objects Review: Imperfect Women And Female Rage

Featured Image: Ritika Banerjee for Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Mridula Sharma is a research scholar and a poet. Her research interests include feminist theory, postcolonial writing, issues of marginality, and contemporary advancements in cinema. She is fascinated with Tristram Shandy and Wuthering Heights. She enjoys reading, writing, painting, and thinking.