Editor’s note: This article is part of FII’s new weekly column on Feminist Economics. The column walks the readers through the field of feminist economics and gives a gender perspective to theory, policy, and the economy.

Mainstream economics is mainly divided into two fields namely micro and macroeconomics. Microeconomics concentrates on individual entities, households and businesses and macroeconomics deals with the behaviour of the economy as a whole. The gender bias of economics becomes even more apparent when we focus on these two fields separately. This article discusses what microeconomics gets wrong about gender.

Theoretically, the two agents of microeconomics are consumers and producers. I would like to begin with the question: What percentage of producers in the economy are women? A very scarce percentage surely. An even feebler number of these women are in decision making roles. The production sector is dominated by men.

Microeconomic models assume the presence of something like an ‘economic man’ or ‘homo economicus’. It implies an ideal person who always acts rationally, he has perfect knowledge and seeks to maximise personal happiness.

A male dominated production sector manufactures goods for consumers which are both men and women. It is generally found that products that cater to women are priced more expensively than the same products for men. While many people argue that women dominate the consumer market as they make decisions for households, it is worthy to note that the nature of consumer decisions made by women and men are different. While women may make consumer decisions on things like food, groceries, beauty, home decor etc, consumer decisions on products like automobiles, real estate, gadgets etc would more likely be made by men.

These two agents of economics—producers and consumers are assumed to make rational choices and act in their self interest.

Also read: We Cannot Talk About Economics Without Talking About Gender

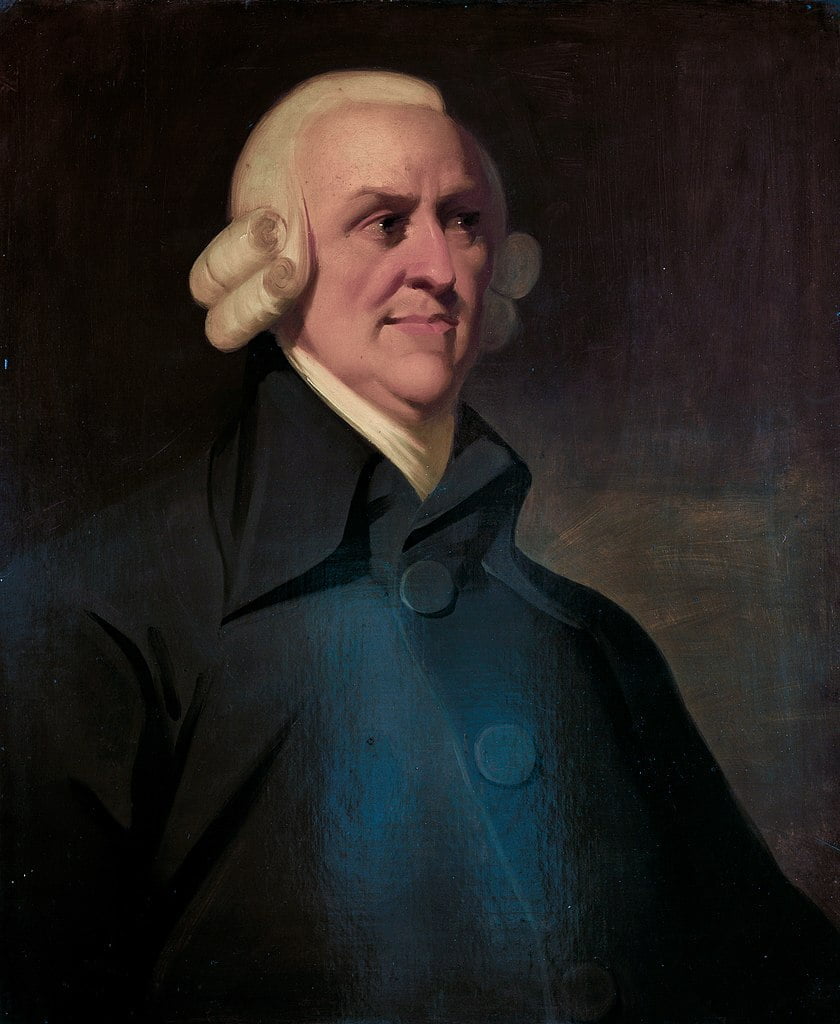

The Scottish philosopher Adam Smith is considered the father of modern economics. In his magnum opus The Wealth of Nations, he writes that, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest.”

Adam Smith’s work is more profound and complex but from here we can take the idea that he propounded self interest as the fundamental force of economics. From Sir Adam Smith we inherited the theory of self interest in modern economic discourse. The idea is that self interest makes the world and the economy function. It believes that when everyone acts in their self-interest we all have access to the goods we need.

As per him, self interest is what puts the dinner on the table. But who cooked his dinner?

Sir Adam Smith never married. He lived with his Mother Margaret Douglas. His mother looked after him and managed the household. She certainly played a role in how Adam Smith got his dinner on the table. Did his mother cook food and serve it to him because of self interest?

Perhaps it would not be very wrong to say that. Back in the day in the eighteenth century, widows and women in Scotland must have not had many options. So Margaret Douglas might have cooked her son food partly out of self interest.

But also because of love, care, affection and other reasons which are not self interest, other reasons that involve sentiments.

I do not think that any butcher, baker, brewer or even Adam Smith could have gone to work if there was no one cleaning, cooking and caring for the children and the old at home.

Also read: What Are The Ways In Which Global Economic Policies Affect Local Gender Issues?

The market economy survives and depends on this other economy which is primarily female. Without women’s unpaid work, these economic markets and structures would crumble down.

Adam Smith forgot about his mother while writing The Wealth of Nations, a work believed to be the product of seventeen years of notes, earlier studies and observation of conversations of economists at that time. Perhaps because Adam Smith forgot his mother, modern economics seems to have forgotten women. The work performed by women is largely invisible and does not even qualify to be called work as per mainstream economics.

A keener understanding of gender can sharpen microeconomic models and aid in gender conscious decision making.

Microeconomic models assume the presence of something like an ‘economic man’ or ‘homo economicus’. It implies an ideal person who always acts rationally, he has perfect knowledge and seeks to maximise personal happiness.

Women perform the majority of the care work. “Care” is an emotional thing. It is not particularly a selfish or a rational act. The ‘homo economicus’ model can be critiqued on this basis. Also, the expectation from an economic man to act selfishly is deeply rooted in toxic masculinity. Men like women are emotional and vulnerable beings.

Behavioural economics also challenged this traditional view of ‘homo economicus’ in the 20th and 21st century. Supporters of behavioral economics say that humans are anything but rational!

Also read: What Is The Link Between Economic Policies And Women’s Rights?

Microeconomics makes many more assumptions and emphasizes certain values which reveal gender bias. Like the “Pareto Optimality” theory, it posits a scenario in which no further improvements to society’s well-being can be made by reallocating resources in such a way that at least one individual prospers but no one else suffers. However, in personal relationships and families there are many instances where one person’s gain benefits the other(s).

Another illusive assumption is that choices of individuals are solely determined by the market. This disregards the influence of emotions on the economic choices we choose to make. Sometimes people buy products exclusively for emotional reasons.

Microeconomics bases itself on the harmful cultural ideas of the ‘masculine’. A keener understanding of gender can sharpen microeconomic models and aid in gender conscious decision making. It will hopefully also visibilise the women that Adam Smith forgot in The Wealth of Nations.

Featured Image: FII

About the author(s)

Shreya is a writer. Issues of how gender affects the economy deeply concern her. She likes to understand the economy, policy, theory, and the world around her with the perspective of gender. When she is not busy contemplating ideas to dismantle gender disparity she can be found cycling or studying finance.