Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for November, 2021 is Popular Culture Narratives. We invite submissions on various aspects of pop culture, throughout this month. If you’d like to contribute, kindly email your articles to sukanya@feminisminindia.com

A lot of analysis and critical engagement has been made with the representation of women in popular culture, especially on digital platforms, in advertisements, films, television shows and so on. Apart from objectifying women- what these dominant narratives do is that they sell an ideology of what an ‘ideal‘ woman should be like. They construct an image that women are then expected to perform and replicate.

What one doesn’t question is- where do these problematic ideas and expectations stem from? How is it that a woman’s demeanor is decided by a man or the men who predominantly control and create such images?

To a large extent, the root of our collective understanding of an ideal woman stems from myths, epics and other religious and cultural texts. It is important to note that often, these conventional, classical and religious texts were narratives by men. The women in these texts are manifestations of what the dominant male morality deemed as the appropriate representation of women and ironically enough, these texts were used as instruction manuals for women to follow and practice.

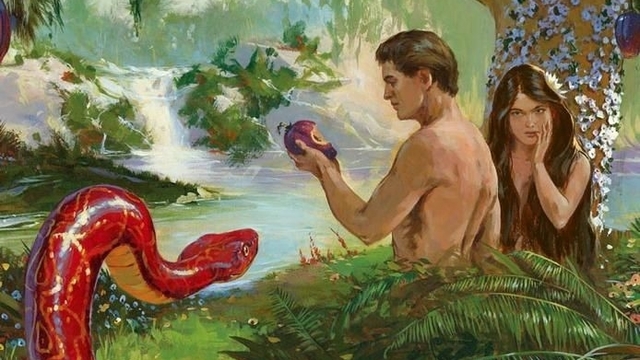

For example, Eve was initially blamed for the fall of mankind, she was depicted as a woman who had lured Adam into eating the forbidden fruit. She could be ‘tempted’ – women are generally portrayed as fickle, unthinking creatures who have to be tamed and controlled if one did not want the fall of mankind. She was portrayed as an unthinking being, as if women are incapable of understanding their own actions.

Eve is said to be created with a rib of Adam. She is created to entertain Adam. In Paradise Lost by John Milton, Eve is only seen through the eyes of the male protagonist around her – her sense, beauty and worth are defined by what men around her think of her. She is not allowed to voice what she thinks for herself, she is denied access to herself and she only sees herself through the reflection in the water once.

Eve is what feminist film critic Laura Mulvey in her essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, calls the production to cater to the male gaze. Eve exists to cater to a specific kind of audience which is predominantly male. Eve becomes the carrier of meaning, not bearer of meaning. She is limited to being a passive object- a desirable body for the men around her.

Sita, the wife of Lord Rama was praised for her chastity. She was praised for being loyal to her husband and for not caving in to the wimps of Ravana, the king of Lanka. She was celebrated as the ideal woman because she was created in the image of what a man thought was a righteous woman. While women like Sita were praised, Surpanakha, the sister of Ravana suffered the worst fate. When Lakshama cuts her nose at the starting of their Vanvas (14 year exile in the forest) the author Valmiki neither sympathises with Surpanakha nor does he reprimand Lakshmana for being physically violent to her

Eve not only becomes the victim of the fantasy of a male narrator, but the extension of a man. She has no independent existence and is only understood and identified as her relation to Adam. While one talks about Eve, it was believed that Lilith was the first wife of Adam but she does not find a place or representation in the dominant narrative.

She was believed to have been created with the same soil as Adam but now she is known as a ‘female demonic figure, derived from the class of Mesopotamian demons called lilû (feminine: lilītu), and the name is usually translated as night monster.’ It was believed that she refused to comply with Adam and did as she pleased. As noted by Satya Chaitanya in Female Subversion: The Spirit of Lilith in Indian Culture, “The Semitic cultures painted Lilith, the woman who disobeyed man and refused to be his inferior, in the darkest possible colors. Thus, in subsequent versions of her story, we see Lilith portrayed with increasing darkness. To begin with, she is the sexual temptress of men in general and a seductress of young men in particular, causing their downfall. Then she is a female demon who causes miscarriages in pregnant women, endangers them in childbirth and kills infants; she drinks human blood and eats human flesh. Eventually Lilith becomes wife of Samael, Satan, and the queen of the realm of evil”.

Also read: A Feminist Reading Of Supporting Female Characters From Indian Epics

Her refusal to submission lead not only to her being co-opted from the narrative but she become a demon woman, a monstrous figure- the wife of the evil that is Satan. She was deemed as a woman who took other women’s children, someone who robbed women from what was essentially depicted as their duty – birthing and rearing children. She is depicted such that she would end up becoming a threat to not only men but also women.

It seems like no matter what these female protagonists did, there were always attempts to reduce them to the smallest entity possible. The only way women found their ways into the narrative is when they behaved like Sita from Ramayana. Women were only legitimised if they were someone’s mother, sister or wife.

One can also wonder how would have these representations differed if they would have been written by women, how the character of Sita written by a woman would have been different. Would she then have enjoyed a fair representation and some space to explore herself as a woman? What if Lilith would have been addressed by a woman – would she still be called a demon for standing up for herself? What is the whole narrative that would have been written by Eve – would we understand better what she felt then?

Sita, the wife of Lord Rama was praised for her chastity. She was praised for being loyal to her husband and for not caving in to the wimps of Ravana, the king of Lanka. She was celebrated as the ideal woman because she was created in the image of what a man thought was a righteous woman. While women like Sita were praised, Surpanakha, the sister of Ravana suffered the worst fate. When Lakshama cuts her nose at the starting of their Vanvas (14 year exile in the forest) the author Valmiki neither sympathises with Surpanakha nor does he reprimand Lakshmana for being physically violent to her.

She is depicted as a demon woman and shamed for her existence. One can also highlight how in plays staged during Diwali, Sita is always depicted as a fair and slender woman while demons in the plays are depicted as heavy and are always enacted by actors who have darker skin tones. Sita is created to suit the expectations of the male audience – ever benevolent and never complaining.

In Ramayana, Kekayi, Dhashrat’s third wife is also depicted as a crude and selfish woman for reminding the king of the boons that he himself had bestowed upon her. She is deemed as cruel and merciless because she is vindictive which only a man was allowed to be. She is demonised for planning and plotting in ways that much shrewder male characters are not. Ironically enough, even that agency is taken away from her and it is iterated through the text that (just like Eve fell in the trap of Satan) Kekayi was ‘influenced’ by her servant and keeper Manthara.

While Kekayi in the epic is reprimanded for having listened to her confidante, when Lord Rama later in the texts abandons his pregnant wife at an ashram because of rumors of his wife’s loyalty, he is not held accountable for putting Sita through such agony. I believe that the sexualisation and objectification of women did not emerge suddenly but has been present since forever. It is only now that we have started questioning it, and hence, upsetting status quo.

One can also wonder how would have these representations differed if they would have been written by women, how the character of Sita written by a woman would have been different. Would she then have enjoyed a fair representation and some space to explore herself as a woman? What if Lilith would have been addressed by a woman – would she still be called a demon for standing up for herself? What is the whole narrative that would have been written by Eve – would we understand better what she felt then? All these questions can be asked now, since we have come a long way into a space and era where we can understand and recognise these patterns to question them, but we still have a long way to go in resolving them.

Also read: Kaikasi: The Forgotten Mother In The Ramayana

Ritika is a student of MA English at Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi with research interest in women’s narratives and literature, gender, sexuality, and narratives on violence. You may find her on Instagram

Featured Image Source: Apollo Magazine