Magazines for women began to appear in various Indian Languages in the mid to late 19th century. These magazines usually contained content on women’s education and condemned social customs that kept women subservient. However, they publications have had a mixed legacy. They portrayed the ideal woman as a capable wife, a nurturing mother, educated yet entirely domestic and remaining true to their traditional function as a helpmate for educated middle-class men.

But when seen in the perspective of their timelines, these publications for women were daring pioneers, pushing the boundaries of women’s roles and social consciousness at a time when they were severely restricted.

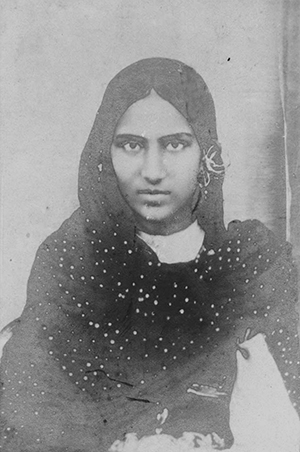

Urdu magazines, among other languages, raised important social issues and helped to enlighten and alleviate the isolation of women in Purdah, all while promoting ideal competent domesticity. The first of these magazines, dating back to the nineteenth century, were founded by men with or without the assistance of their wives or other female companions.

Syed Ahmad Delhavi founded Akbar-un-Nisa (Women’s News) in Delhi in 1887, which was the first women’s monthly in Urdu. It closed after a brief run but became an inspiration for later journalists. Maulvi Muhibbi Hussain started another Urdu periodical for women, Mu’allim-i-Niswan (The Women’s Teacher), in the late 1880s. The journal featured essays on women’s education, women in other nations, poetry, and an article about the purdah in almost every issue.

A humorous piece by a purdah supporter in one issue pointed out that women are confined in purdah to defend their honour, but the outcome is that unfortunate ladies are locked up because men could misbehave. The author then said, “Why don’t males instead follow purdah?“. Maulvi Muhibbi Hussain, who revolted against purdah in a radical fashion more than a century ago, is still a point of reference for people in the twenty-first century.

Another notable piece of writing published in Tehzeeb is Khaddar-poshi (Wearing Khaddar), deeply nuanced in its discussions on the everyday issues associated with wearing hand-spun and woven khadi fabric as a garb. Last but not least is the time-defying piece Gavarment hawwa nahin hai (Government is not an ogre), which delineates and demystifies the modern (albeit colonial) state-subject relationship and encourages female readers to criticise the government while turning away their fear

Tehzeeb-un-Niswan (Refinement of Women) started in 1898, a weekly Urdu newspaper for women founded by Sayyid Mumtaz Ali and his wife Muhammadi Begum as the editor, is the next in line. It aimed at reaching the women at home. Beside news items, it included speeches from women’s organisations, as well as the names of women who had received BA, MA, or other degrees, along with warm congratulations and exhortations to other readers.

Articles on the contemporary political scene, WWI events, non-cooperation, and swadeshi began to appear in later volumes of Tehzeeb. Tehzeeb, which contained some breathtaking articles that pushed the boundaries set at the time, including: School ki ladkiyaan (School-going Girls), was a spirited counter-offensive on prevalent stereotypes of the time about young women who attended school.

Another notable piece of writing published in Tehzeeb is Khaddar-poshi (Wearing Khaddar), deeply nuanced in its discussions on the everyday issues associated with wearing hand-spun and woven khadi fabric as a garb. Last but not least is the time-defying piece Gavarment hawwa nahin hai (Government is not an ogre), which delineates and demystifies the modern (albeit colonial) state-subject relationship and encourages female readers to criticise the government while turning away their fear.

Tehzeeb’s ideal domesticity may now seem dated, but its advocacy of women’s education and of border imaginative horizons for women in purdah were in advance of the time.

Another husband and wife team active in women’s education who started a journal to further that cause were Shaikh Abdullah and Wahid Jahan Begam. They founded the Urdu monthly Khatoon (ladies) as the publication of the All India Women’s Educational Conference‘s women’s education division in 1904.

Also read: Fouzia Dastango: The First Woman In An Urdu Storytelling Tradition

Khatoon is a valuable source of information on the history of Muslim women’s education. The journal primarily discussed educational issues, curricula, the advantages and disadvantages of teaching English to women, the need for improved textbooks, the students’ need for fresh air and exercise (behind high walls so that purdah could be maintained), and reports from women’s association and school committee meetings.

Khatoon’s main goal was to promote and encourage women to pursue education. Khatoon served its purpose and was discontinued in 1914 when Abdullah was required to run a boarding girls school in Aligarh.

Ismat of Delhi, created in 1908 by Rashidul Khairi, was another important Urdu journal for women in the early twentieth century. Ismat was promoted as a journal for “respectable Indian women” (sharif Hindustani bibiyan), with high-minded articles about valuable and required knowledge for women, including intellectual, cultural, scientific, historical, and literary knowledge, but not political knowledge.

Authors in Ismat occasionally used female pseudonyms in their publications. The reasoning behind this was that a girl reading such an article would believe that she, too, could write something and be motivated to contribute.

The content of these periodicals was far ahead of its time and is still relevant today. They helped us think, rethink, and question our understanding of Muslim women’s minds, as well as their hopes, ambitions, dreams, and their contribution. We have made significant progress with women in general, and Muslim women in particular, are in far better positions; they have laws protecting them, they are working in almost every field, they are active in politics and they are writing and speaking for themselves

Later, publications of Ismat covered a broader range of political issues, such as support for Muslim women’s rights to inheritance and divorce as per the Shariat Application and the dissolution of Muslim marriages bills, which were being debated in 1937-39. Women’s movements in other countries, particularly Egypt and Turkey, as well as the issue of suffrage in Europe, were discussed with occasional references to the Indian nationalist movement.

All of this was evidence not only of women’s increased activism, but also of the fact that those involved in the production of women’s journalism were following as well as leading their readers.

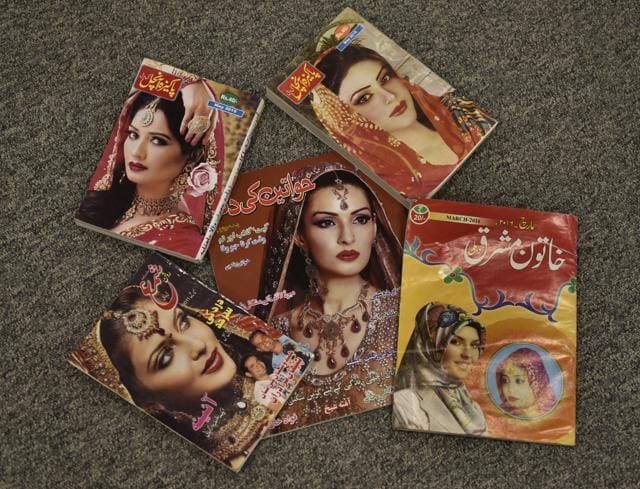

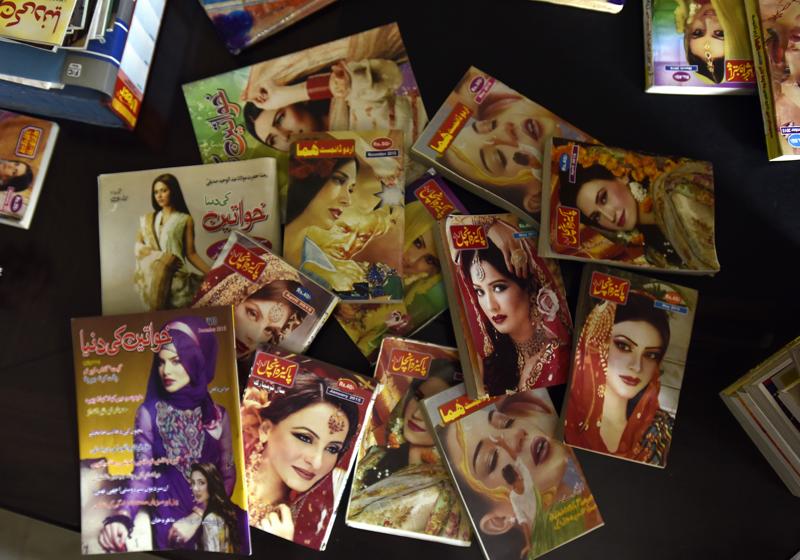

These journals paved the way for others, and in the decades since, an array of women’s Urdu magazines have appeared, some edited by men, but the vast majority by women. Some had long runs and established literary reputations, while others were more fleeting. Some used a nationalist tone and sentiment, while others remained politically neutral. Based on a few volumes scattered around, it’s impossible to draw broad conclusions about the content and style of these journals.

The content of these periodicals was far ahead of its time and is still relevant today. They helped us think, rethink, and question our understanding of Muslim women’s minds, as well as their hopes, ambitions, dreams, and their contribution. We have made significant progress with women in general, and Muslim women in particular, are in far better positions; they have laws protecting them, they are working in almost every field, they are active in politics and they are writing and speaking for themselves.

But there is still much more to be done. Nonetheless, what inspired millions of women a century ago will continue to inspire millions of women today to speak up for themselves, stand up for themselves, and do something for womanhood.

Hiba is a feminist and an independent researcher. She believes that all humans are equal and looks forward to work for women’s empowerment and equal opportunity. You may find her on Instagram.

Featured Image Source: Hindustan Times