American literary critic Sandra Gilbert and author Susan Gubar, in their examination of women’s literature and literature from a feminist perspective, have coined two important terms- “anxiety of authorship” and “schizophrenia of authorship.” The former addresses the dilemma that women authors like Virginia Woolf face in terms of the fear of not being taken seriously, but at the same time losing their identity by claiming that they are at par with their male counterparts. The latter refers to the conflicts that women writers often engage with, their desire for expression being constantly threatened or thwarted.

Struggling with such anxieties and insecurities, women writers have constantly been looking for unique narrative techniques and genres to attack the established societal norms and introduce their audiences to new, experiential realities in their works. A genre that is frequently used by the women writers is that of the short story.

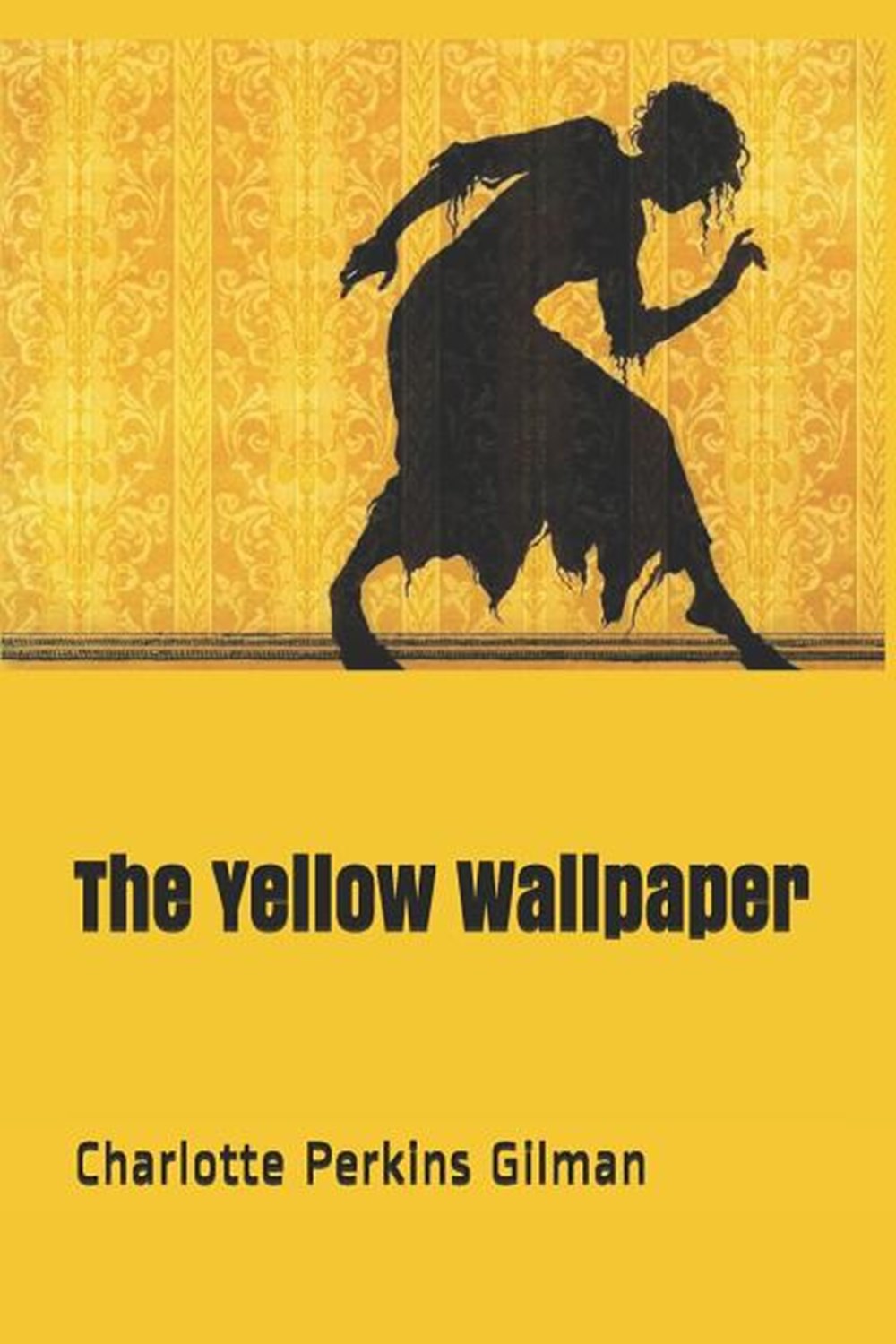

Katherine Mansfield’s ‘Bliss’ and Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s ‘The Yellow Wallpaper,’ can be used as relevant examples to examine how women navigate the genre in their own respective ways.

The locus of both the stories is the domestic space and the point of commonality lies in the way the protagonists use that space to exhibit their creativity. In ‘Bliss‘, the protagonist Bertha Young blissfully arranges the fruit basket and the cushions in a disorderly manner thus, symbolising her transgressive nature.

Even though the protagonist Jane in ‘The Yellow Wallpaper‘ is restricted by her family from putting her creative faculties to use, she secretly writes in her diary. Always under surveillance, she is rendered alone. On the other hand, Bertha gets to indulge in ‘intellectual’ conversations with her elite Bloomsbury group.

The reader also notices the uneasy and disturbing marital relationships in both the stories. In ‘The Yellow Wallpaper,’ John constantly infantilises his wife by referring to her as “little girl” and “my little goose.” Furthermore, he perceives his wife to be naïve and fragile, incapable of any sensible decision-making. Being the authoritative figure, he doesn’t pay heed to her worries about her health and prescribes her the rest-cure treatment.

Due to the economy of the short stories, symbols are used to depict the states of mind of the characters. The pear tree in ‘Bliss’ becomes an important symbol that reveals Bertha’s psyche and offers her epiphanic moments. The yellow wallpaper in Gilman’s story becomes a symbol of entrapment, of how women are trapped in their conventional gender roles and just want to break free of the shackles of patriarchy

Drawing from her personal experience, Gilman offers a critique of this now infamous treatment. Instead of recovering, Jane sets on her descent to madness as her mental health worsens.

In ‘Bliss,’ the reader observes how Bertha and Harry have two extremely different personalities. While Harry is associated with a certain grotesqueness and is curt, Bertha judges people on their intrinsic qualities. One can’t help but notice that Bertha’s naivety is beyond her years and her fear of sharing the marital bed with her husband. This highlights how the marriage lacks sexual intimacy.

Nevertheless, both the women are forced by their circumstances to refrain from expressing their feelings. Their inability to articulate their thoughts is displayed by the writers through devices such as ellipsis and hyphens. Moreover, another reason could be that the language to etch the thoughts the two of them were trying to convey were still unavailable to them as there were very few examples of women writing about experiential truths in literature at the time.

Also read: Gynocriticism: A Female Framework For The Analysis Of Women’s Literature

Many feminist literary critics have highlighted the problem of how language is phallocentric and how it denies women the opportunity to communicate their desires and feelings. At many instances, Gilman has employed parenthetical comments to bring forth the protagonist’s thoughts. But Mansfield’s protagonist leaves things unsaid and the story is thus, filled with ambiguity.

Due to the economy of the short stories, symbols are used to depict the states of mind of the characters. The pear tree in ‘Bliss’ becomes an important symbol that reveals Bertha’s psyche and offers her epiphanic moments. The yellow wallpaper in Gilman’s story becomes a symbol of entrapment, of how women are trapped in their conventional gender roles and just want to break free of the shackles of patriarchy.

A significant characteristic of both these stories is the presence of female bonds. Bertha thinks that she shares a kind of spiritual connection with Pearl Fulton, but it turns out to be ephemeral. Even in the other story, Jane feels as if a woman is trapped inside the wallpaper, just like she is trapped in the house and the patriarchal structure. Both characters wish to run away from their situations, and have a sense of solidarity towards this imaginary women.

Language itself is largely masculine, and short stories have been a significant outlet for women to attempt to establish a language of their own through literary devices like, metaphors, symbols and punctuations. In that sense, the evolution of short stories by women writers must be read as the assertion of their anxieties, world view and their declaration of dissent

Both these stories also critique another role that is heightened and glorified by the society as a sole responsibility of women – motherhood. While suffering from post-partum depression, Gilman’s protagonist lacks the intimate bonding and longing a mother is expected to have to see and be with her child.

Since it is a semi-autobiographical text, it endorses Gilman’s belief that a child’s upbringing is a community’s task and the workload of the domestic space should be distributed between the husband and wife. Bertha Young disrupts the routine of her baby and we notice how the nanny claims proprietorship of the baby.

The ending of ‘Bliss’ is bleak as Bertha is left disheartened that her husband is involved with another woman. Whereas in ‘The Yellow Wallpaper,’ John lies prostrate on the ground by seeing his wife “creeping” around the room, symbolising the fall of the misogynist and the patriarch.

Also read: We Need More Angry Women In Fiction: ‘Female’ Rage And Her Inner Worlds

The short story is a genre that provides women the opportunity to narrate their stories, without taking much of their time. We must look at this literary genre in the context of the reality that women’s time is gendered and allocated between various assigned roles, leaving them very little time to indulge in their creative pursuits.

Language itself is largely masculine, and short stories have been a significant outlet for women to attempt to establish a language of their own through literary devices like, metaphors, symbols and punctuations. In that sense, the evolution of short stories by women writers must be read as the assertion of their anxieties, world view and their declaration of dissent.

Featured Image: The New Yorker/ Hanna Barczyk

About the author(s)

Taanya is currently pursuing her Master’s degree in English Literature from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. Feminist Studies and Postcolonial Studies pique her interest. She reads all genres but has a special liking for LGBTQ literature and women’s writings. Her other obsessions include street food and strong coffee