The world, for worse, is more divided than ever. It’s conflict-ridden, full of fake news, jingoism, and afraid of diversity. Owing to these and many other factors, people are being displaced, and their rehabilitation is one of the world’s biggest crises. This crisis, no surprise, is manufactured, for it takes a little political will and planning to settle displaced people. A lack thereof reflects poorly on the ‘host’ country, showing their non-commitment to humanity.

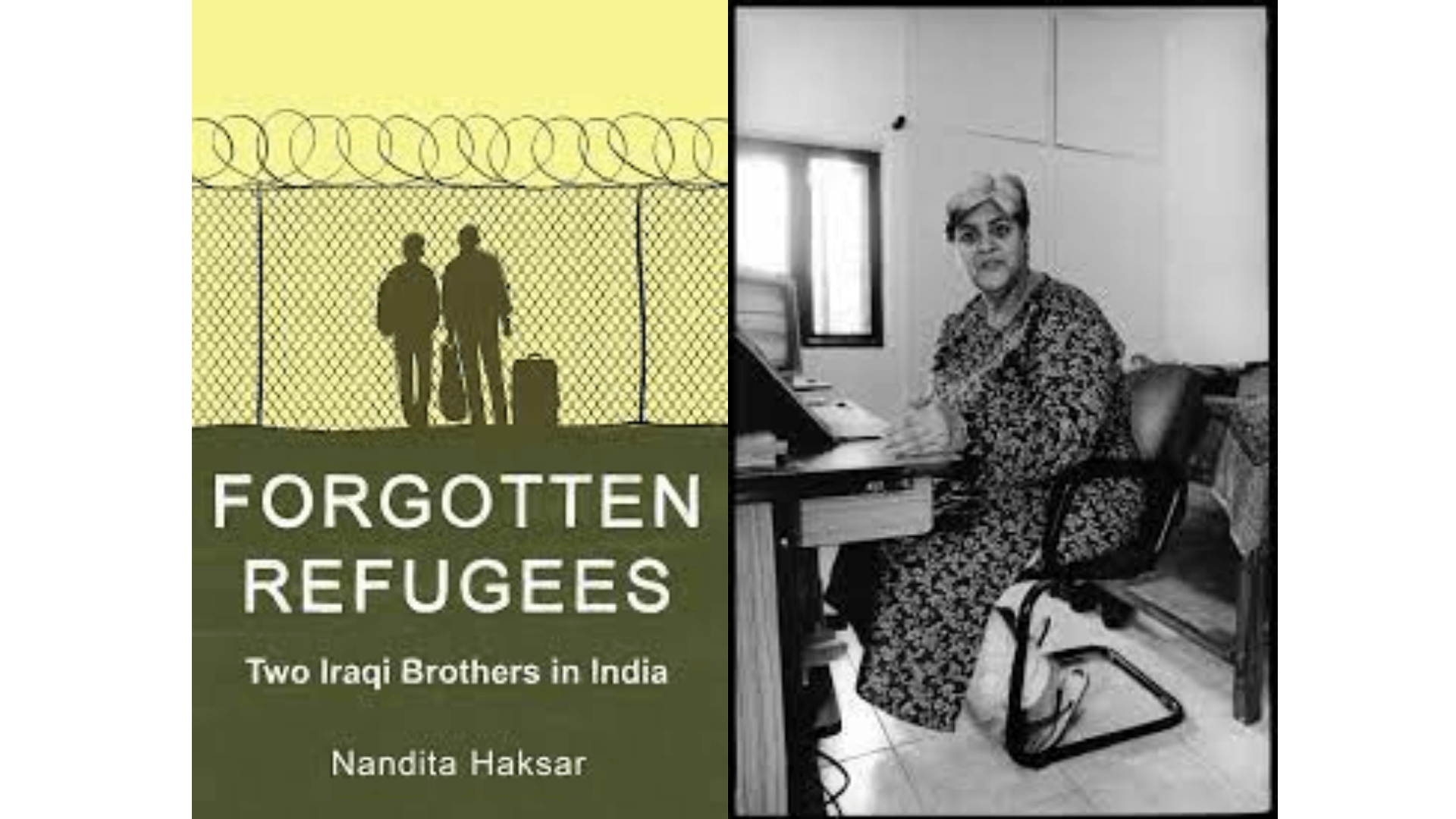

However, one never thought of India as such a country. But India has been a deeply racist and xenophobic society for aeons. As most stories never get told, these aspects of India got little to no attention. But Nandita Haksar’s book Forgotten Refugees: Two Iraqi Brothers in India (Speaking Tiger, 2022) does precisely that: it holds a mirror to the Indian society.

Haksar, who remains deeply committed to humanitarian causes, writes that in telling the story of these brothers — who chose for themselves the names Babil and Akkad, after Babylon and Akkadian Empire, respectively, to protect their identities and for the safety of their family. She learnt a lot about “many aspects of India’s history and its connections with Iraq.”

Be it a ‘friendship’ treaty that India signed with Iraq decades ago. Or perhaps the slight difference between their ‘seekh kebabs’ that these brothers noted (theirs are “much longer and with different spices”), each detail in this book signals shared humanity between the people of these countries. Over the years, however, the situation in both has witnessed a three-hundred-and-sixty-degree shift.

Babil and Akkad’s case is not the first that Haksar was asked to take up. She had previously interviewed Hazim Adeem Hussain and his brother Anwar back in 1998 “to see if they came under the definition of refugees and merited UNHCR protection.” In the Goan jail, these brothers “had a wonderful experience when someone told him that it was Eid and offered him a small carpet to pray. The other inmates, mostly Hindus, joined him [Hazim] as he led the prayers.”

Also read: Tamil Refugee Women In India: The Unsung & Stateless Who Saved Their Families In Exile

Be it a ‘friendship’ treaty that India signed with Iraq decades ago. Or perhaps the slight difference between their ‘seekh kebabs’ that these brothers noted (theirs are “much longer and with different spices”), each detail in this book signals shared humanity between the people of these countries. Over the years, however, the situation in both has witnessed a three-hundred-and-sixty-degree shift.

These details sit very oddly with present-day India, where religious intolerance has reached its zenith under the Modi-led BJP government. The impression of the experience that Hazim and his brother had had of India perhaps was the one that Babil and Akkad’s maternal uncle and aunt must have had, which is why they suggested the brothers leave for India instead of any other country and suggested they attain a refugee status from the UNHCR. But contrary to what they imagined, both – India and the UNHCR – betrayed them.

One of the admiring qualities of this book is that Haksar doesn’t muzzle Babil and Akkad’s voices. They’re telling their own story here, and Haksar only anchors them and tethers their inputs into a binding narrative. And besides recommending what we should do as a civil society to help refugees, she, the ‘author,’ is technically not there.

What the brothers recount in this book is a nightmare. It is not only a record of their nostalgia for their homeland but also a record of the hurt they felt in India.

Babil notes that as a twenty-six-year-old, when he boarded a plane from Baghdad to Hyderabad for the first time, he should’ve felt excited, but he wasn’t. But some part of him convinced him that this warmongering would be over soon, and he’ll be back: to his mother and the land. However, after seven agonising years now, despite the unchanging socio-political situations in their country, he continues to “hope like an ‘idiot’ that Iraq will one day become a truly independent country.”

While leaving their country, the brothers placed their trust in India, which their aunt said is a place where people of all faith live happily and that the brothers “would not face any problems on account of being Muslim.” But India, as they were told or its citizens knew, changed for everyone alike, but more catastrophically for the Muslims. This is what Babil has to say: “Delhi did not turn out to be the India of our imagination; it was not friendly and welcoming. We faced hostility, prejudice, and even utter indifference.” The brothers, during the pandemic, were forced to leave a rented place. They were made to pay a bribe to the police just to be left alone to their own devices. They had to stage a dharna outside the UNHCR office just to be heard. Except for Haksar, who only not heard them but also welcomed them to her home, no one paid attention to their agony and trauma.

Also read: Climate Refugees: The Forgotten Victims Of Climate Change

“Delhi did not turn out to be the India of our imagination; it was not friendly and welcoming. We faced hostility, prejudice, and even utter indifference.” The brothers, during the pandemic, were forced to leave a rented place. They were made to pay a bribe to the police just to be left alone to their own devices. They had to stage a dharna outside the UNHCR office just to be heard.

Towards the end of the book, Haksar makes an appeal to treat refugees as people, not statistics. Because saying that “9.2 million Iraqis are internally displaced, or refugees abroad” as of early 2022 can only invite a reaction, not empathy. They’re not numbers, but people with a beating heart, looking for a safe sanctuary when their all has been snatched away.

Featured image Source: wikipeacewomen.org