I remember encountering the “Veiled Rebecca”, at the Salar Jung Museum in Hyderabad, back in 2018. The marble sculpture created by Italian neoclassical sculptor Giovanni Maria Benzoni is known for its spectacular finesse in bringing out textile-like fluidity to a material as solid as marble.

The sculpture draws context from the Biblical reference of Rebecca, a modest woman, who veils herself upon meeting her future husband, Isaac. As a woman in her late twenties and at the cusp of political awakening, encountering the sculpture of a full-bodied, seemingly shy, veiled woman, displayed in a space that mostly has male visitors, was conflicting to me.

Not to take away from Giovanni’s craftsmanship or artistic vision, but the lived experience of being a woman makes it excruciating to focus on the aesthetics of objectification. As much as I marvelled at the measure and control of the artist over his medium, I could not help sensing the titillation in the hall, continuously making me want to hold Rebecca by the hand and release her from the predicament of being looked upon with no respect for her personal space.

The intersection of gender and spectatorship in art cannot be elaborated on, without invoking feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure And Narrative Cinema”, one of the most disruptive, debated treatises on how gaze plays out in cinema. Though Mulvey’s theoretical disposition is anchored on the medium of cinema, it’s political positioning of gendered gaze can be extended to other forms of art that are based on visual stimulation, and the interactions between the work of art and the spectator.

I have always felt like an outsider in museums and galleries. The discomfort of being unable to enjoy the beauty of works created largely by male artists with female subjects has coerced me into silent complacency, out of the fear of being ridiculed for being the only person in the group who wants to ‘bring gender’ into everything. But for a woman, everything is gendered. I do not need to bring it into anything, by will.

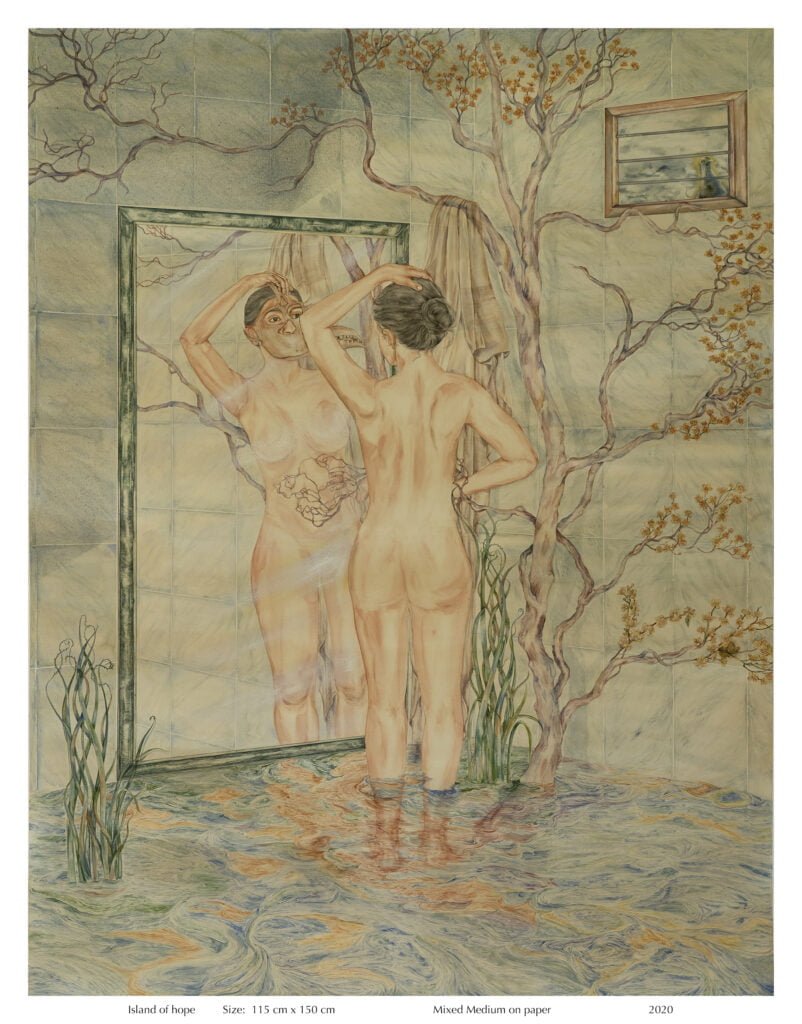

A few years later, when I had almost given up on expressing my complex feelings inside art galleries, I encountered a large canvas painting of a woman that instantly made me feel seen, heard, and understood. Artist Anupama Alias’s works at the Lokame Tharavadu (The World Is One) exhibition in Alappuzha, brought me home to myself.

The art exhibition featuring the works of over 260 artists, started in Alappuzha and Ernakulam districts of Kerala on April 18, 2021. The two-month event was collaboratively organised by the Kochi Biennale Foundation, Departments of Tourism and Culture and Alappuzha Heritage Project.

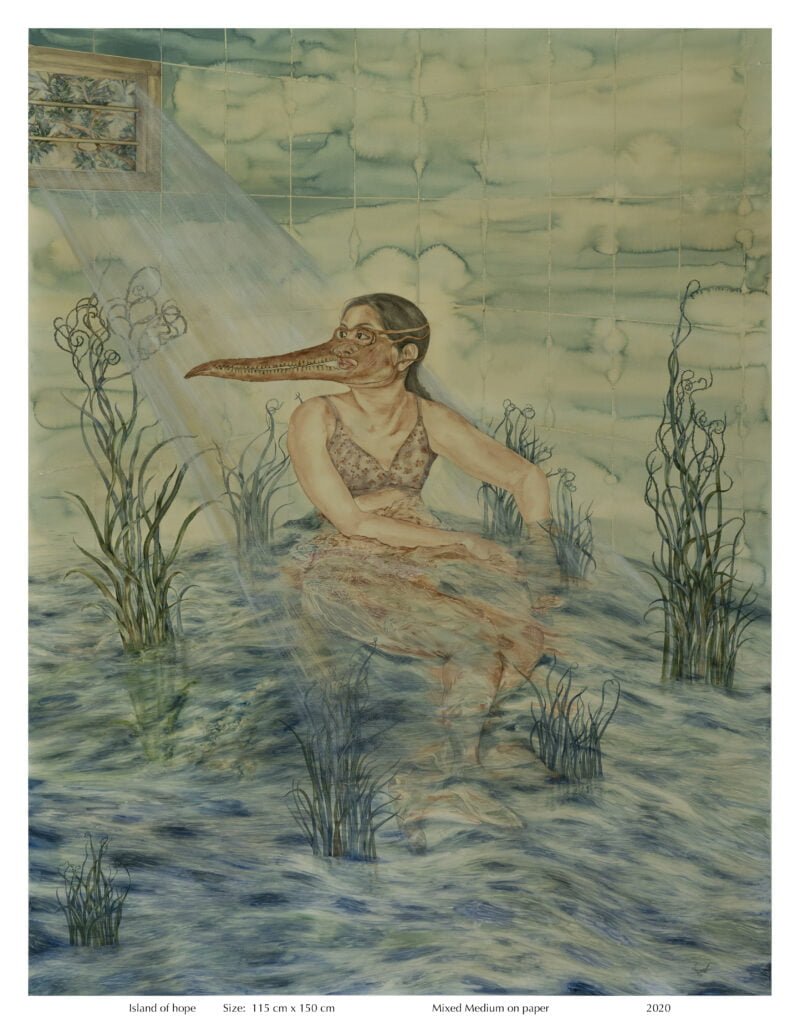

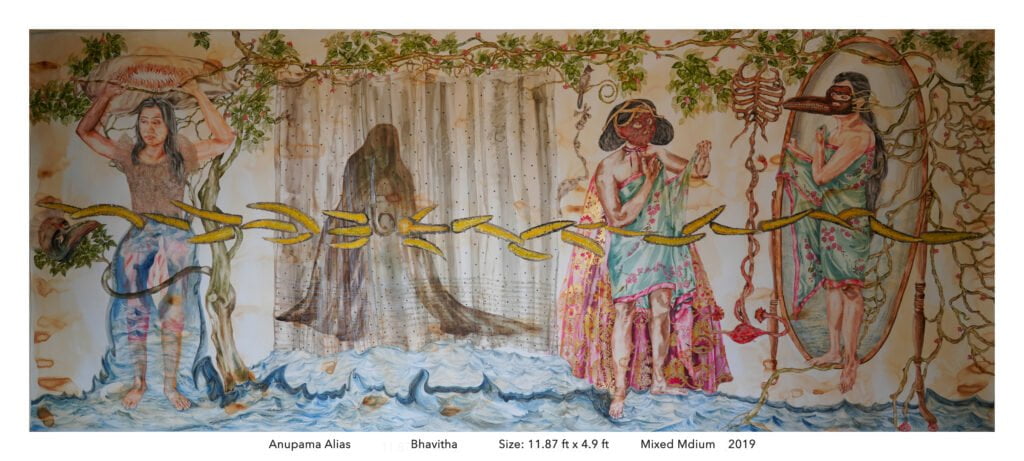

“My artwork reflects the way I see the society I live in. It addresses rapid shifts and inflictions of everyday life on us. I have engaged myself with my paintings to speak with myself about the turmoil that I am going through over the past years. I sense depth and try to trace my being and becoming. It is a battle with the veils. It is a struggle to stab the interiority- the protagonist follows the sky, and hears her bones and cells. She becomes the sound and the form as well,” reads Anupama Alias’s artist statement, describing her series named Bhavitha (The One Who Imagined).

‘A battle with the veils’ instantly decreased my emotional and political disconnect with “Veiled Rebecca”, a burden I had been carrying for years. I spent a long time engaging with Anupama’s paintings that day, the relief of womanly solidarity that justifies the feminist conscience of ‘bringing gender into everything’.

Anupama Alias was born in Kerala and lives and works in Kochi. An alumnus of the S.N. School of Arts and Communication, University of Hyderabad, Anupama is the recipient of various prestigious awards, scholarships, and felicitations. I could not help but reach out to Anupama, mostly to thank her for speaking to me like nobody else has through her paintings, but also to understand the experiences that have shaped her art and voice.

Given below are excerpts from my email correspondence with the artist.(the responses, originally in Malayalam, have been translated to English)

Q. Could you elaborate on your academic journey as an art student and your foray into the art fraternity?

I joined the Master of Fine Arts (Painting) course at Hyderabad University after completing my Bachelor’s and Master’s in Advertising, from RLV College Of Music and Fine Arts, Kochi. Situated in an IT hub like Hyderabad, the University, with excellent faculty and a facilitating atmosphere for growth contributed immensely to shaping my artistic vision. The multi-cultural student pool and exchanges that followed, opened me up to experiencing spaces and exploring artistic media in newer ways.

The course mandated that we work on a medium other than painting and sculpture. This is what led to my experimentation with cotton as canvas, and I was able to exhibit work from this series for my final year course completion show.

My art is reflective of the spoken and unspoken struggles I have experienced. As an individual, I believe that the artist must be in constant dialogue with what surrounds them, especially the intersectional implications of multiple marginalisations on fellow human beings. I have faith in the disruptive capacity of art and think that the artist is someone who must strive to reveal layers that may be invisible to the populist, majoritarian, gendered conscience of the spectator

This paved way for the opportunity to exhibit my work at Kalakrithi Gallery and Srishti Art Gallery in Hyderabad. Later, I was invited to showcase my work at the Young Subcontinent Show, which was part of the Serendipity Art Festival, curated by artist Riyaz Komu. Since the project was funded, it offered me the liberty to explore my artistic expression without compromises or compulsions.

I believe that my experience at the University of Hyderabad is what tethered me to my core as an artist. Our work studios at the campus were open round the clock, and often, I would come back to my hostel room very late into the night, after fruitful discussions with fellow art students from all genders, and spending time with my own paintings. My senior at the university introduced me to art historian and curator, Bhavana Kakar. Now, I work with Latitude 28, her creative collective.

Though I have not lost opportunities owing to my gender in my home state, I wonder if the restrictive moral and institutional atmosphere within campuses and art circles in Kerala allows female artists to fully pursue their potential. My family, friends, and faculties at the University of Hyderabad have played an undeniable role in making me my own individual and artist.

Also read: Disrupting Gender In Public Spaces: Dr. Indu Antony’s Project ‘Cecilia’ed Always’

Q. Your Artist Statement at the Lokame Tharavadu exhibition mentions that you aspire to use art as an intervention to disrupt surface regularities. Could you elaborate on what you feel is the space an artist must occupy in society?

My art is reflective of the spoken and unspoken struggles I have experienced. As an individual, I believe that the artist must be in constant dialogue with what surrounds them, especially the intersectional implications of multiple marginalisations on fellow human beings. I have faith in the disruptive capacity of art and think that the artist is someone who must strive to reveal layers that may be invisible to the populist, majoritarian, gendered conscience of the spectator.

Our society has always been in a constant state of evolution and awakening. Artists must work to further this, and make the world a more equal space than it was. In today’s times, women and trans individuals are beginning to claim more space in our public and private conscience, and the expressions of the protagonists in my paintings – their urge to spread, fly, and become – are manifestations of my own artistic journey as a woman and political individual.

Q. Your paintings encompass women in various settings, but mostly alone. Most of the exhibits are mammoth-sized, and within them, your protagonists come across as isolated and anxious. What makes you explore the female experience through these emotions? Do you feel the lives of women are largely dominated by these feelings owing to their gender?

My father is an artist. He would travel extensively, and be home only for a few days every month. It was me, my mother, sister and my grandmother in the house, most of the times. I have grown up and been most intimate with women’s lives, and perhaps, that is why most of my protagonists are women.

My mother is a steadfast individual who stood her ground even in the face of isolation and restrictive social sanctions. She taught me by example to be self-reliant and resilient. But that kind of resilience, which springs out of necessity for a woman, also produces a sense of alienation despite being amidst people. The experiences of having to find ways out of hostilities by myself are what inform my paintings. Thus, my women survive, but feel inadequately understood.

Most masks in my paintings worn by my protagonists are beak-shaped. The beak is an organ that belongs to birds, and birds are creatures of liberation. Ritualistic traditions across the world that involve the use of masks were often restricted to men. In my paintings, women wear beak-shaped masks, own their emotions, and step into the netherworld of strength that lies untapped deep within them

My experience apart, I also feel that even within families which have the physical presence of male members, women have to abide by unwritten gender roles. Most women are conditioned to romanticise such micro-aggressions on their personhood in the name of love and patronisation.

Though there is a younger breed of men who have come to realise and acknowledge their gender privilege, the number is skewed. When faced with conflicts, women still wonder what lies ahead for them if they choose to fight patriarchal institutions like marriage. This anxiety of uncertainty is socially engineered to ensure that women eventually ‘fit into‘ their assigned gender roles.

The women who protest against this are often erased from history. The truth is that it is the contributions of various forgotten, unnamed, faceless women that have helped us grow into the space we are in, today. For me, it is important to document these women who are solitary, despised, and pushed into oblivion for quarreling with the status quo.

Q. An unmissable element in your paintings is the masks that women wear. How did you arrive at the decision to fit your women with masks, and in your vision, what do they symbolise?

I began working on this series in 2018. My exposure to African masks at a museum was perhaps the seed of the concept. I feel that masks offer immense possibilities for a woman to transcend her social conditioning. Especially in the context of the pandemic, masks cover up human anxieties, vulnerabilities, and aspirations by restricting access to full facial expressions. It becomes a shield to self-protect from being emotionally found by those around us.

If one looks into the history of African masks, it can be seen that they are worn in during ritualistic practices. Theyyam, Kerala’s ritual art form is also very similar to this, incorporating movements, mimes, and anecdotes from the tribal histories of communities who continue to invoke the tribulations and strife of their ancestors through the performance.

The Theyyam artist dons a mask and for the duration of the performance and lapses into a trance, wherein they become the deity/ancestor themselves, conversing to their people in the common tongue. Often, the performers of this art come from oppressed caste locations, and the dominant caste individuals bow before them, accepting their divinity for brief moments.

My artistic aspiration has always been to evolve and elevate my personal conscience to match that of my art. Any work of art comes from the experiential, historical, political, and moral truths of the artists. In that case, if the art is to be separated from the artist, the aesthetics of such vacuumisation is a subjective experience pertaining to individual spectators. As time passes, the artist in the art will invariably reveal themself, and the art itself must be re-interpreted keeping in mind renewed political and social sensibilities

This subversion of intersectionality has always fascinated me. This capacity for transcendence that a mask offers, allows me, as a woman, to embrace facets of my personality and identity that are socially contained by gendered, discriminatory expectations.

Most masks in my paintings worn by my protagonists are beak-shaped. The beak is an organ that belongs to birds, and birds are creatures of liberation. Ritualistic traditions across the world that involve the use of masks were often restricted to men. In my paintings, women wear beak-shaped masks, own their emotions, and step into the netherworld of strength that lies untapped deep within them.

Q. In the post #metoo world, do you feel it is possible to separate the art from the artist? Art often comes from a personal space of truth, and hence, is it justified of an artist to deviate from politically progressive artistic values in their personal spaces?

The #metoo is an extremely important movement that offers survivor solidarity and space to address the power equations in gender-based abuse. While reflecting on whether an artist’s work must be disenfranchised or de-platformed as a consequence of a #metoo allegation, I think we need to also delve into some contextual factors.

The two main elements of a #metoo accusation are the abuser and the survivor. In that duality, it is politically imperative that we stand with the survivor, who is jeopardised by a lack of gender privilege, social support, and capital. The separation of art from the artist, and the ascribing of a separate, independent identity to art, without taking into account the dispositions of the artist, is an idea that is unpalatable to me.

My artistic aspiration has always been to evolve and elevate my conscience to match that of my art. Any work of art comes from the experiential, historical, political, and moral truths of the artists. In that case, if the art is to be separated from the artist, the aesthetics of such vacuumisation is a subjective experience pertaining to individual spectators. As time passes, the artist in the art will invariably reveal themself, and the art itself must be re-interpreted keeping in mind renewed political and social sensibilities.

For example, this is something I heard from someone: if an artist who usually paints children as their subject, is later accused of pedophilia, their personhood cannot be separated from their art. The re-interpretation of their art then becomes a discourse on gaze, intent, and a fantasising conscience in their art.

The heart of art spectatorship lies in how one engages with a piece of art. It is important for the spectator to be sagacious, and exercise political and progressive caution while interacting with art. A spectator who is informed of the historical, intersectional, and gendered context of a piece of art would be discerning, so as to not give a blanket sanction to the artist to be celebrated for his art, without scrutiny.

The crux of a #metoo allegation is based on a crime that has already allegedly been committed. No crime deserves benevolent interpretations. I believe that no amount of artistic proficiency or volume of artistic work can be cited to cover up a predator’s criminal behaviour. In any scenario where an individual alleges abuse, the conversation should be about finding ways to address it, as well as making space for them to heal and find justice. Artists have no special stature to bypass this scrutiny.

Anupama’s responses remind me of Australian writer, comedian, and actor Hannah Gadsby’s resounding Netflix stand-up special Nanette, where she takes down art history’s systemic misogyny through comedy. Interrogating Picasso’s contributions to painting, Hannah says, “Picasso is important. Cubism is important. Picasso freed us from the slavery of having to reproduce three-dimensional reality on a two-dimensional surface. He said we need all the perspectives possible on a subject. But let me ask, are any of those perspectives a woman’s?”

I started this piece by recalling my experience at the Salar Jung museum. The works of artists like Anupama Alias offer the promise of women being heard, included and understood while engaging with art.

Also read: Artemisia Gentileschi: The Artist Whose Work Is A Love Letter To Survivors And Female Solidarity

You may find Anupama on Instagram

About the author(s)

Sukanya is a lawyer-turned-journalist with experience in writing, editing, development communication, and advertising. She holds a graduation in law, a post-graduation in philosophy, and a post-graduate diploma in print journalism. She is also a published poet and was awarded the All India Poetry Prize in 2015. Her journalistic work is deeply focused on gender and intersectionalities, and they appear in Feminism In India, True Copy Think, and The News Minute.