The nude tradition in European oil paintings has been in existence for ages. It is known for showcasing the skills of European artists over decades and portraying the socio-cultural history of Europe through both an emotional and a political lens. The striking factor is the nude figures of males and females that speak to us through these lenses.

The tradition found its origin during the later classical period in ancient Greece and Rome. Over time, scantily clothed nude bodies have been sketched and painted by numerous artists who have given us some of the best art pieces.

What strikes however is how expressions of nudity have always differed in paintings of female bodies and those of male bodies. Most famous artworks offer us, naked women, far more than naked men. A casual viewer of such paintings may appreciate the sheer intricacy and aesthetics of the art in these bodies, but a careful observer shall see through the quantity and quality of nudity expressed in male and female bodies in these paintings.

The women in these paintings seem to have minimal roles contributing to the moment depicted in them. However, the roles of the men depicted in them are seen to have far more significance in the progress of events that take place in the respective paintings.

Art critic John Berger, in his work Ways of Seeing, has called this phenomenon ‘men act and women appear’. In this article, we shall trace a few famous European paintings that have enabled this phenomenon despite their brilliant artistry.

‘Shame’ expressed contrarily in male and female nudity

Some of the first nude paintings were drawn based on Adam and Eve. As the story of Eve goes, God had punished her for having touched the forbidden fruit by multiplying her sorrows in the form of conception and childbearing. In the 15th century, artist Pol de Limbourg’s painting Fall and Expulsion from Paradise depicted the story of Eve from Genesis in detail.

Shame is a theme that slowly developed after the consumption of the forbidden fruit as per the Biblical reference of Genesis. Adam and Eve suddenly went through a realisation after the consumption of the apple that they were naked. The themes in paintings then eventually shifted from nakedness to a projected consciousness of shame that comes with it.

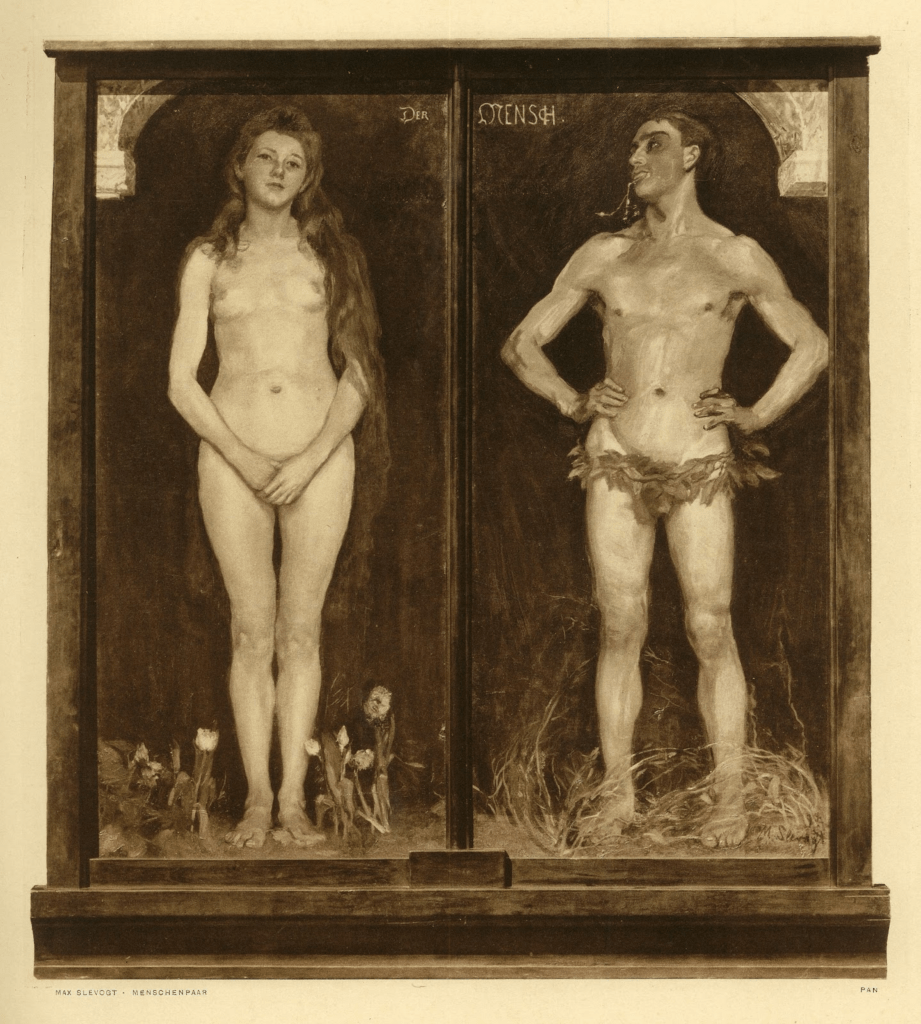

The Couple by Max Slevogt shows fig leaves drawn on Adam’s genitals to hide this shame. However, there is a sort of subordination in the figure of Eve where the same is depicted. The way in which her naked body is painted, slightly curled and shy beside Adam’s casually dominating posture, is one of self-consciousness and shame. Instead of fig leaves, she uses her hands to cover her genitalia, indicating her discomfort with her own nakedness.

As Berger says, she often looks away from her lover and looks out of the picture “towards the one who considers himself her true lover – the spectator-owner”. This element once again proves how the woman subjects in these paintings have no contribution whatsoever to the moment being captured. Their only true value lies in the gaze they draw upon themselves from the onlookers

Another painting called Adam and Eve by Mabusa shows a similar depiction of shame by covering their genitals with leaves. The contrast between the postures of the male body and the female body remains the same as that in The Couple. When compared to artworks like Michelangelo’s David, the absence of action and a life force in Eve’s body unlike that of David, who is also a representation of Adam, is certainly clear.

Therefore, shame becomes subservient in art featuring male figures because of their momentary action in facial features and bodily gestures. However, this shame easily overpowers the nudity of the female figures because of their inaction and self-consciousness.

What strikes the most is how despite both the figures of Adam and Eve being aware of their nakedness, shame is a factor reflected mostly through Eve.

The consciousness of nudity between the female subject and the spectator

With time, the theme of shame in European paintings was transformed from religious depictions to quite explicitly expressed ones. Nakedness was now portrayed not just through its realisation in the female subject, but also by hinting at the spectator’s awareness of it.

The 17th-century series Susannah and the Elders by famous Baroque artist Tintoretto is a popular example where the subject directly communicates her shame to the spectators. The perception of nakedness is exercised directly in the subject-spectator dynamic as Susannah, along with her peeping voyeurs, and the spectator, takes part in gazing at her own body.

Something quite remarkable in these paintings is how the female subject looks directly at the spectator, making them aware of her conscious nakedness. They play not much role in taking notice of the other subjects in the painting, may it be lovers or voyeurs.

Susannah is pursued and later touched by the peeping voyeurs, yet she remains steady in her inaction. While this might be synonymous with passivity, she is also invoking sexual pleasure in her onlookers.

This is where the element of gaze comes in and the element of shame gets its invocation through the spectator’s perception only. Von Aachen’s painting Bacchus, Ceres, and Cupid is also another example where the woman breaks the fourth wall and looks straight at the spectator, instead of the male lover present right beside her.

Berger says, “Women are there to feed an appetite, not to have any of their own”. It implies that there is a sexual competition between the male counterparts and the spectator, served by the naked woman subject through her docility and inaction. The contrasting purpose of the naked male and the naked female is thus solved, which is, to act and to appear, respectively

As Berger says, she often looks away from her lover and looks out of the picture “towards the one who considers himself her true lover – the spectator-owner”. This element once again proves how the woman subjects in these paintings have no contribution whatsoever to the moment being captured. Their only true value lies in the gaze they draw upon themselves from the onlookers.

Action in men and inaction in women expressed through nudity

As mentioned earlier, the naked bodies of women have been portrayed in European oil paintings in their inaction. In Felix Traut’s Nude Girl on a Panther Skin, the causality in the lying woman’s body gesture is highly contrasted to that in other paintings. She is as if, waiting for something to happen to her, instead of doing something herself.

The principal protagonist is usually never painted, yet somehow we think of it to be male. The reason behind this is how the female subject, while also serving their nakedness for self desire, precisely entertains the male gaze.

For example, in Angolo Bronzino’s Allegory of Time and Love, the posture of the woman subject representing Venus, has no relation whatsoever with whatever action is taking place around her. She is being kissed and touched by the naked Cupid, yet, she does not take action.

Berger says, “Women are there to feed an appetite, not to have any of their own”. It implies that there is a sexual competition between the male counterparts and the spectator, served by the naked woman subject through her docility and inaction. The contrasting purpose of the naked male and the naked female is thus solved, which is, to act and to appear, respectively.

All these paintings have made their way into popular culture today because of their aesthetics as well as the depiction of a developing socio-political Europe. However, we should never see them excluded from the historical or feminist context.

To understand art fully, one should apply various lenses and political contexts. Artforms exist in their nuances and like John Berger envisioned, each one of us should recognise them through our observations.

Also read: Meera Mukherjee: An Artist Who Carved Her Own Space In The Male-Dominated World Of Sculpturing

Featured Image Source: Creative Bloq

About the author(s)

Mrittika is a student of English. She is usually found expressing her love for art through words and music. At other times she is most likely traveling around the town trying new delicacies and imagining her life as a Greta Gerwig movie

One of the reviewers of my historical novel “Cupid and the Silent Goddess”, which imagines how Bronzino’s Allegory was created, suggested that the figure of Venus had been painted from a male model, not an uncommon practice at the time (consider Michelangelo’s beefy “female” angels). Look at her squared-off left thumb, much more like that of a man, and furthermore, no woman ever had breasts like that.

See also: https://www.pagedor.co.uk/books/p/cupid-and-the-silent-goddess-alan-fisk

I don’t remember the last time I read something as good as yours.. Fellow examiner at your CUET exam’s. 😂