Tagore’s writing deserves to qualify as a feminist writer. When I started reading Rabindranath Tagore, my social conditioning compelled me to look to the West for progressive thought. The fundamentals of feminism were The Second Sex, A Room of One’s Own among others. And although these books are universal in themes, I wished for a voice closer to home: give me context over feminism through the lens of Indian women, my mother, my grandmother, my widowed boss and my own life in this distinctly vibrant land.

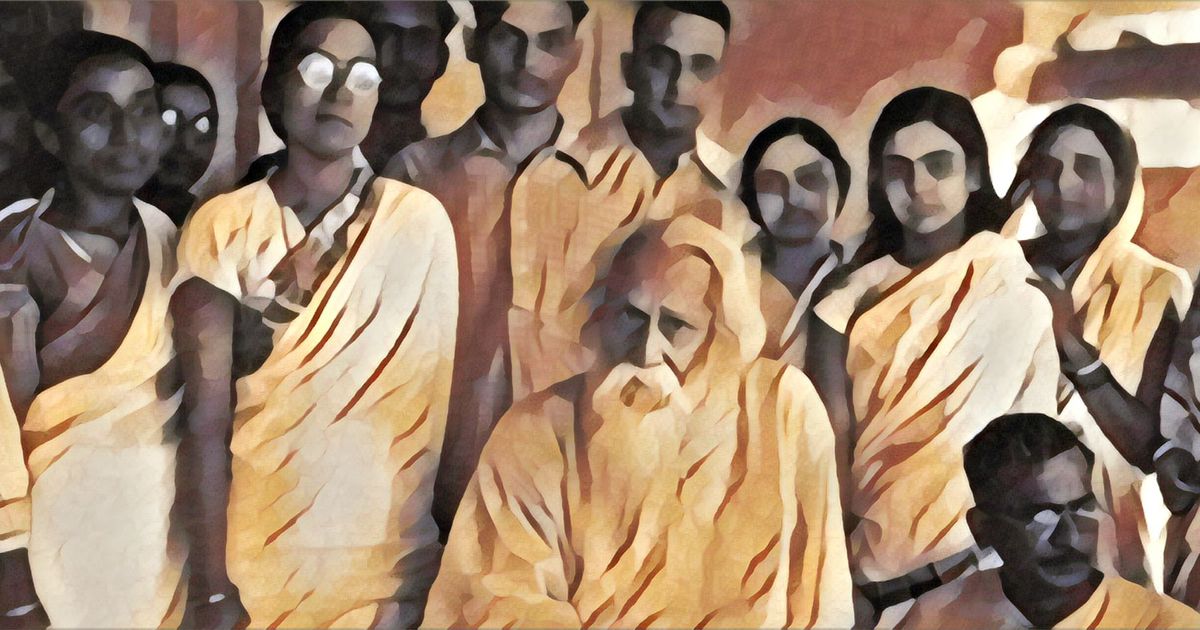

Rabindranath Tagore wrote about the real women of colonial India in all their raw glory, when they were way ahead of it, maybe even to the present day. Women confront questions of chastity, sexuality, domesticity, and, self-identity. I am writing about three women from his works who shaped my understanding of feminism not through ideals, but the complexities of every life of a woman.

Binodini from Chokher Bali

This famous widow of Indian literature is entirely at odds with the Indian TV stock character of a widow, who is adorned in a white saree and always in tears. Binodini is an electric force, best introduced by Tagore at the onslaught of the novel-

‘An irate queen bee stings everyone that: comes in her path, and similarly, an irate Binodini was prepared to destroy everyone around her. Obstacles, and nothing but obstacles, that is what she had faced all her life. Was there no way that she could find some satisfaction, some amelioration? If she could find no happiness, then whoever stood in her way to frustrate her, whoever was instrumental in depriving her of all that she deserved, whoever conspired to deny her what were her rightful dues, would be mercilessly crushed and humbled. Vengeance would be hers.’

– Rabindranath Tagore

Since widowhood was not her choice, Binodini refuses to be desexualised as a swami-khaki (devourer of her husband). In the story, she befriends a mother and her daughter-in-law to enter their home and seduce the son and husband, Mahesh Babu. The reader would expect her to morph into a classic enchantress. A likely similarity in the manifestation of Raja Ravi Varma’s painting of the most famous femme fatale of Hindu mythos- Mohini.

But she later realises the inconclusiveness of destroying a happy marriage, wherein in the end, no one finds love. She renounces her material life and leaves for Kashi to seek homage as a widow. Although Tagore confessed regret over the ending, he succeeded in posing the question: if the society itself launches a widow into sexual politics, why is it thrown off when she masters it?

Gandhi lauded a choiceless ascetic widow as the perfect satyagrahis, because of her endurance for suffering. It was ‘one of the greatest gifts of Hinduism to humanity. Female sexuality remains under India’s white garb of modesty, morality and invisibility. The story of Binodini is significant because it recognises a woman’s agency towards her physical needs, something Indians are still not comfortable talking about.

Also Read: Finding Feminism In Rabindranath Tagore’s ‘Streer Patra’

Chitarangada from Chitra: The One Act Play

In 1913, the one-act play Chitra, set the stage for a woman as the lead in Mahabharata. The play is Tagore’s lyrical adaptation of the love story of Chitrangada and Arjuna.

Chitra, born as the princess of Manipur is brought up by her father as a boy destined to ascend the throne, both as a warrior and a future ruler. She chanced upon Arjun, wandering in her forests while in his 12-year-long exile. The character Chitra proposes to Arjuna for marriage! But Arjuna dutifully declines, keeping in check his vow of celibacy in exile.

But Chitra pursues her passion and gets a boon from the God of love (Kama) and God of seasons (Vasanta) to attain a form of ‘perfect feminine beauty for a year’. This time, when she appears before Arjuna, he declares himself a ‘love-hungered guest at her door’.

As their affair intensifies, it mirrors the stages of a modern-day relationship. And at every step, Chitra stuns one with her higher understanding of love and companionship.

It starts with the couple’s fiery attraction toward each other. But Arjun’s instant enchantment with her physical appeal incites a sudden realisation and a sharp disgust in Chitrangada. He has fallen for her dark eyes and milky-white arms. She asserts, “Surely this cannot be love, this is not man’s highest homage to a woman!”

Eventually, they spend time together and a personal romance flourishes between them. I love the bit where Chitra confesses her standing to Madana if she is to be Arjuna’s partner:

“I would stand by his side as a comrade, drive the fierce horses of his war-chariot, attend him in the pleasures of the chase, keep guard at night at the entrance of his tent, and help him in all the great duties of a Kshatriya, rescuing the weak, and meting out justice where it is due.”

– Rabindranath Tagore

Then comes the time for commitment, and Arjuna is all for it. He proposes marriage. But plot twist again, Chitra respectfully declines, knowing they have no future beyond Arjuna’s exile. “This love is not for a home!” she asserts. There sure is pain, but she tells Arjuna not to hold any regret. “Take it and keep it as long as it lasts.“

Also Read: Kadambari Devi: Rabindranath Tagore’s Literary Companion | #IndianWomeninHistory

And let’s call it ‘the nerve’ to reject the proposal of the most popular figure of not just the Pandava but the whole of the Kuru pantheon. Shall it disquiet the fundamentalists that the frontman of dharma in Mahabharata admired a perfectly independent woman to the extent of marrying her? He did not deny the longings of flesh to himself nor her and put consent first at every step.

Arjuna hence falls deeper for her spirit over body and virtue over beauty. As the year draws to an end, so does Chitra’s boon. In the final act of disillusionment and complete acceptance, Chitra comes clean, with her identity, inhibitions, love and deceit. And even in her request for forgiveness and acceptance, she holds her integrity.

“I am Chitra. No goddess to be worshipped, nor yet the object of common pity to be brushed aside like a moth with indifference. If you deign to keep me by your side in the path of danger and daring, if you allow me to share the great duties of your life, then you will know my true self.”

– Rabindranath Tagore

Arjun’s reply is terse but sufficient, “Beloved; my life is full.“

Chitrangada strikes a chord with me. Her image can be said to be that of an ancient-day tom-boy struggling with beauty standards on an internal and societal level. Moreover, she is much closer to modern sensibilities regarding female sexuality, marriage as a choice and pre-marital sex. Suppose dating and relationships are infamous to Indian culture. Why does the religious text that we swear by hold the evidence of lovers courting each other for a year without marriage? We need many more stories like her to counter the fundamentalistic narratives that pronounce these anti-cultural concepts, keep women in a subordinate position through and define gender roles through selective readings of Hindu scriptures.

Mrinal from Strir Patra

If you believe there is strength in softness, this is one read that will always set you alight with hope. Tagore wrote Strir Patra (A Wife’s Letter) in 1914. The story flows in the form of a letter, Mrinal, a wife, writes after leaving her husband.

In a time when women were not allowed to vote, and formal education was demoralised. While the domestic scheme of gharsansar ensured their territorial confinement to the andarmahals, the purdah system mandated the physical concealment of their bodies. And although Strir pratra got banned in 1829, brides had not ceased to burn. Dowry deaths swelled in Bengal.

The letter is a reflection of 15 years of Mrinal’s soulless marriage. Mrinal is married into a well-to-do family in Kolkata to the second son. Her good looks had made up for the dark-skinned wife of the first son. The matter that this trophy wife might have great talents becomes a problem.

Through the 15 years of marriage, Mrinal hides away and writes poetry in the cowshed every day, suffers a miscarriage and witnesses the suicide of the ill-treated, low-caste relative in the home, whom she raises for years as her daughter.

Also Read: Swarnakumari Devi: The Forgotten Author And Activist Of The Tagore Family

She elopes from home in silence to the beaches of Puri. In front of the ocean and under the monsoon skies, she relinquishes her identity:

In the world of 20th century India, Mrinal did not suffer what people would typically call grief. She saw no poverty or physical abuse, but that is precisely the notion that Strir Patra imparts the deserved significance to that domestic dissatisfaction and mistreatment are not dramatic acts of violence. That women (and men) should strive for more than the standards of a seemingly happy marriage that the tradition glorifies.

If marriage is the divine union of a woman and man, that union is only possible when both parties stand on equal ground, otherwise, they simply fail to transcend their material reality. A woman does not enter the institution of a marriage with the sole purpose of service to the man and the household. Our identities are so much more than that. And it often requires mustering the courage to listen to our inner voices and reassess the roles created for us but not necessarily by us. We can or can not choose to be a wife, a daughter-in-law, or a mother. And regardless of what our choices might be, it is so important to have our inner lives known.

I often wonder what became of her after that. Did she become a poet? Did she find love? Did she cradle a child to her bosom? But you see, there is no perfect happy ending in the tale where the princess saves herself.

Harshala slings her ink, professionally and otherwise. Her parents think it’s just a phase. Sigh. Hence, she is a brand strategist from 9-5. But most of her writing revolves around queer issues, children’s literature and food history. She lives in Mumbai and is as local, rounded and grounded as a vadapav. She can be found on Instagram and Linkedin.

Beautiful!