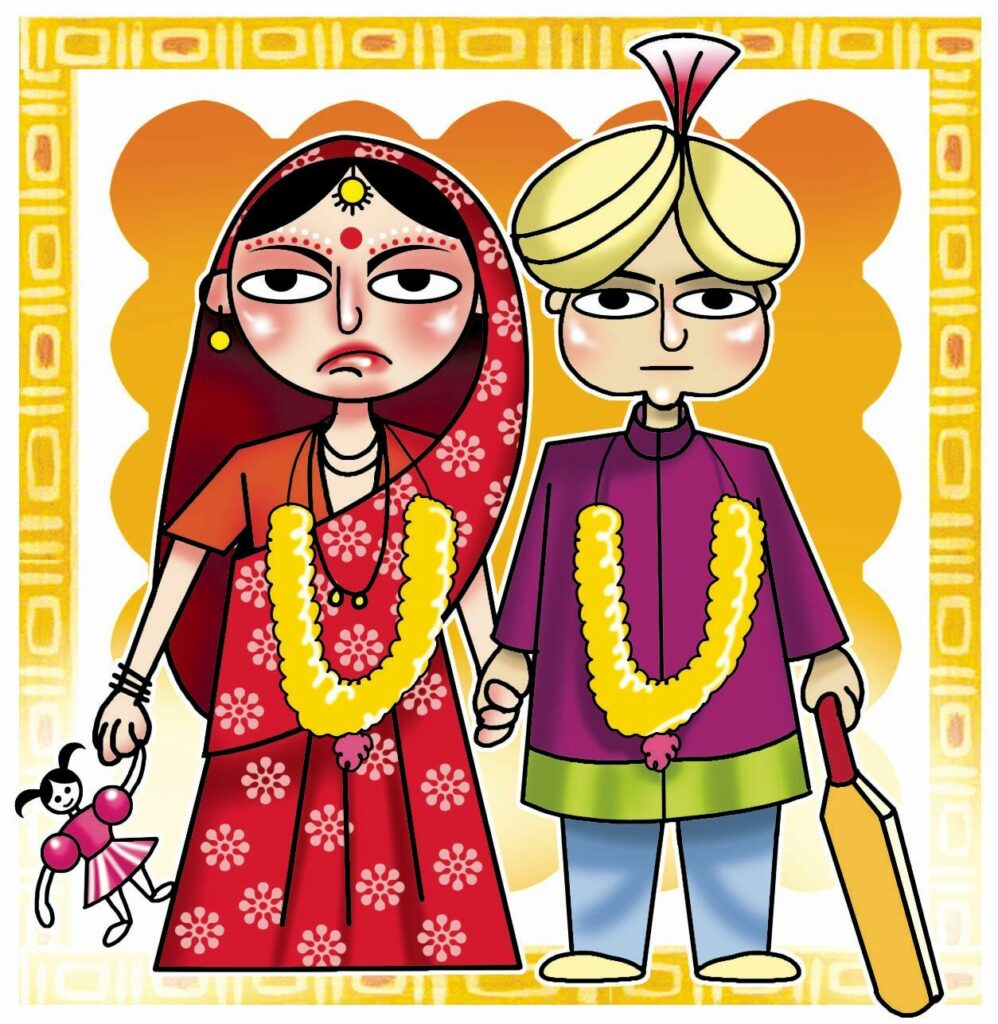

The social institution of marriage in India has been around for centuries and can be dated back to the Vedic period (c.1500 – c. 1100 BCE). The modern conception of marriage has come to associate itself with the union of families, and the renaming of property and is even believed to be a milestone in one’s life in the Indian tradition as a whole.

The importance that the Indian society attributes to this institution has opened up spaces for various questions about its legality in the context of the law. A question like ‘what should be the legal age for marriage for women in India’ has often garnered varied opinions from major social stakeholders.

According to the District level housing and facility data, close to 48% of married women in the 20–24-year age group have tied the knot before 18 in rural areas, as opposed to 29% in urban areas. Over a span of the last 15 years, child marriage has declined by 11 per cent which means less than one per cent annual decline. The Annual Healthy Survey that was conducted in 2011, showed a more rapid decline in nine states that were surveyed.

Marriage as a social institution

In 1929, the legal age for marriage in India was 14 years, according to the child marriage restraint act and after independence, the law was amended twice and it was in 1978 that the marriageable age for women was increased to 18 years. At first glance these 4 years don’t seem like a long jump to the naked eye, however, if one were to analyse the social settings and the dynamics of the relationship between a husband and a wife, it is a case in point of how India has come a long way.

Also read: How Do Marital Adornments Impact Women’s Lives?

During the 1970s, women were often married as soon as they started menstruating which inevitably reduced their role to mere child-bearers and child-rearers. Starting their families at such a young age, women were confined to domestic duties and their education more often took a backseat.

This cycle continues and women end up feeling powerless, which is another reason why they have started accepting patriarchy and becoming their agents.

A study conducted by Sheela Singh and Renee Samara, used data from 40 demographic and health surveys and highlighted that a significant proportion of women in developing countries continue to marry as adolescents.

It is also notable that the education and age of the female during their first marriage were strongly associated at both the individual and societal level: A female who has attended school until 10th grade (secondary school) was less likely to marry during adolescence, whereas in countries with a higher proportion of women, having completed secondary education, the proportion of women who married as adolescents are lesser than that.

Also read: Marriage For Women: Inevitable And Problematic All At The Same Time?

Moreover, the identity of these young married women thus gets reduced to the role their ancestors played in relationships like that of the mother, the wife, or the daughter-in-law. Consequently, this led women to have a lower socioeconomic status which exempted them from having any fiscal power. This cycle continues and women end up feeling powerless, which is another reason why they have started accepting patriarchy and becoming their agents.

Most recently, the cabinet proposed the legal age of marriage in India be increased from 18 to 21 years for females, supported by the Child Marriage Restraint Act and the Special Marriage Act, 1954 and the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006.

It is interesting to note that according to the per capita income, the role of men and women in the household started to become more fluid, as a result of which, women were seen to be equal contenders in the familial space.

The increase in this age is seen to be a step in the right direction for safeguarding the agency of women in terms of choice and freedom to exercise this choice. This increase in age has reduced an inherent social obligation on women to bear children as soon as they reach reproductive age. While legally we are headed in the right direction to foster gender equality in a society such as ours, we are yet to socially uproot the evil of assumed choices that are forced upon women.

Most recently, the cabinet proposed the legal age of marriage in India be increased from 18 to 21 years for females, supported by the Child Marriage Restraint Act and the Special Marriage Act, 1954 and the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006. On the 74th anniversary of India’s independence, the Prime Minister stated that the government would have to consider the minimum age of marriage for girls, based on a suggestion from a committee made by the Union Ministry of Women and Child Development.

Marriage will always be inherently unfeminist

The practice of marriage in India is laced with patriarchal challenges -the dowry system, the systematic and systemic subjugation of women and has created undue pressure on women to become mothers. Marriage along with its social obligations has also normalized the loss of women’s individualism and agency as human beings. The life women lead after marriage also affects their professional careers and calls into question their identity about their own families.

According to research on “Indian Matchmaking: Are Working Women Penalized in the Marriage Market in India?”, which looked at Shaadi.com profiles of women, how male suitors respond to questions relating to work and income, and if their interest wavers. “The unfortunate reality is that there is a sizeable penalty in the marriage market for women who express an interest in pursuing a career after work,” wrote Diva Dhar, author of the study and a researcher at the University of Oxford.

“There is a sharp drop in response for women who want to continue working after marriage … women who have never worked received 15-22% more interest in the marriage market as compared to women who want to keep working.“

Diva Dhar

To experiment, Dhar looked into marital profiles of women on Shaadi.com, which were seen to perpetuate caste and class biases, in addition to reinforcing gender stereotypes. The profiles were based on women in real life and varied across all caste groups.

Also read: The Fragrance Of Unmarried Women & The Djinns Of Patriarchy

The study found that there were namely 5 categories -women who have never worked and showed no interest in working after marriage; women working with a low income (somewhere between Rs. 2,00,000 and 4,00,000 per annum) and wished to continue working post-marriage; women working with a low income and who wished to not continue working post marriage; women working with a high income (Rs. 7,00,000-1,000,000 per annum) and wished to continue work post marriage; women working with a high income and wished to give up work post marriage.

The study aimed to understand whether males responded poorly to women who were working professionals thereby exposing the inherent thinking patterns which aim to exclude women from earning. It was observed that the most popular women on these matrimonial sites were those who didn’t work and expressed no interest to work; as many as 70% of men responded to their profiles.

“There is a sharp drop in response for women who want to continue working after marriage … women who have never worked received 15-22% more interest in the marriage market as compared to women who want to keep working,“ says Dhar.

Considerably, this trend was seen to be more prominent among privileged caste groups such as Brahmins and Agarwals. Therefore, marriage can place an absurd amount of ‘duty’ on women to fit into roles the society feels good, taking away from them their own choices.

Therefore, it can be seen that marriage as a social institution needs much reform and legal reforms should be accepted in the social context. While raising the legal age of marriage in India is a mark of progress for society, and marriage as an institution remains unfeminist owing to the norms it enforces on women. True progress is yet to be made to ensure freedom from the social evil of patriarchal marriages.

About the author(s)

Anshula Agarwal is a third-year student of Political Science currently based in Gurgaon and has an immense love for language, literature and movies. She comes across as witty, cheerful and a dedicated individual who is eager to learn things. Some of the things that interest her include basketball, cheesy romance novels, and good conversations.

Women-centric laws have made marriage difficult for men who face harassment from wives and in-laws,bare falsely accused of dowry and domestic violence, and these innocent men either rot in jail or even if they are able to prove their innocence, they lose their job and reputation in society. Many men commit suicide. Even the families of men are arrested on a mere complaint of a woman. Many women misuse the law to threaten and extort lakhs of rupees after a divorce. Many women demand half of a man’s property and assets, alimony, and child support. Men always lose child custody and wives don’t let husbands see their children.