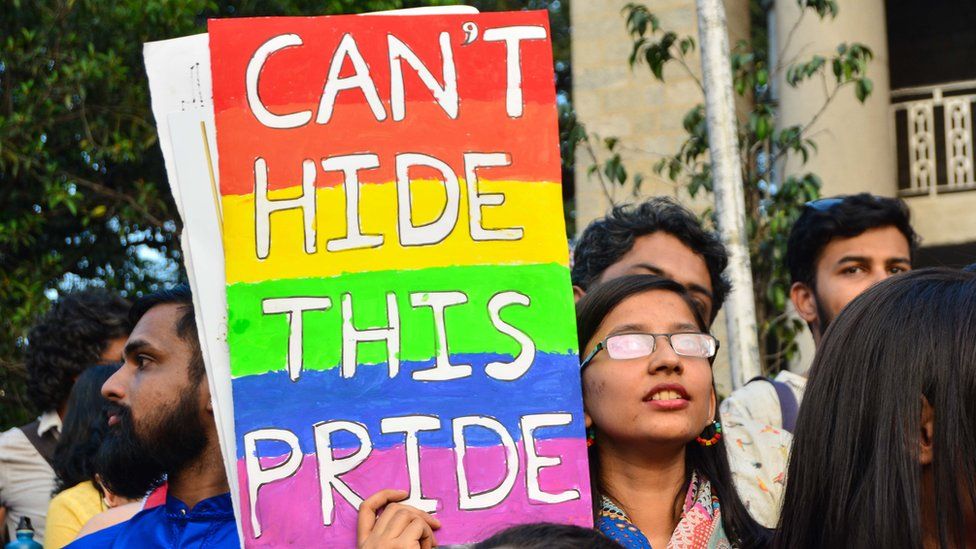

Recently, a couple petitioned the Supreme Court for legal recognition of same-sex marriage under the Special Marriage Act, by challenging the heteronormative idea of Indian marriages and provision to legally recognize their marriage. The petitioners filed the Public Interest Litigation under Article 32 of the Indian Constitution in the interest of the LGBTQ+ community.

The petition made an argument that marriages between the members of the LGBTQ+ community must be acknowledged, as fundamental rights are for everyone, irrespective of their status and identity, to enjoy. The legal framework of marriage should, therefore, re-evaluate any restrictions based on one’s gender identity and sexual orientation. Such restrictions stand in violation of the fundamental rights protected by Part III of the Constitution, including Articles 14, 15, 19(1)(a), and 21.

The Special Marriage Act was enacted in 1954 in an attempt to uphold the secularity of the country mentioned in our Constitution. The Act was designed to be a piece of legislation that regulates weddings that cannot be solemnised owing to religious traditions, under the Hindu Marriage Act, or Muslim Personal laws. This act was implemented to create consistent legal safeguards for those who desire to marry across their own classes or religions.

These legal bindings on same-sex couples cause pragmatic hindrances. In this case, Parth Phiroze Merhotra and Uday Raj Anand have been in a relationship for many years and are now raising two children. But without the legal validation of their marriage, they are unable to acquire a legal parent-ship over their children.

The Supreme Court, a two-judge panel led by Chief Justice of India D Y Chandrachud, issued a notice to the Centre in response to petitions filed by Supriyo Chakraborty and Abhay Dang, as well as Parth Phiroze Mehrotra and Uday Raj Anand. The panel, which also included Justice Hima Kohli, noted at the beginning that identical cases were pending at the Delhi and Kerala High Courts.

Following the legalisation of same-sex relationships, the Arun Kumar Anr. v. The Inspector General of Registration and Ors. case in 2019 was another important step towards inclusivity. It reevaluated and deconstructed the meaning of ‘bride’ mentioned in Section 5 of the Hindu Marriage Act. Arunkumar married Sreeja, a transwoman, according to Hindu rituals and customs. Their appeal for marriage registration was refused by the Registrar of Tuticorin.

There have been several cases over the last few years where the heteronormative approach to marriage has been questioned time and again. In 2018, Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India created a revolution when the court decriminalised sexual relations between two consenting adults of the same sex. The court mentioned that there is no discernible distinction between people who engage in “carnal intercourse outside the order of nature” and those who engage in “natural” intercourse. The Supreme Court’s five-judge panel decisively repealed Section 377, making same-sex relationships between consenting adults legal. This decision, however, did not address the legality of marriage.

In the NALSA v. Union of India verdict, the Supreme Court reinterpreted the meaning of ‘sex’ in Article 15 where the Constitution states that the State cannot discriminate against any citizen on the grounds of race, sex, caste, and place of birth.

The National Legal Services Authority of India (NALSA) filed the petition to officially acknowledge those who do not fit into the male/female gender binary prescribed by society, including those who identify as “third gender.” This was a groundbreaking ruling in which the Supreme Court for the first time officially recognized “third gender”/transgender people and examined “gender identity” in depth.

The Court acknowledged that third-gender people had fundamental rights under the Constitution and international law, breaking the socially recognised notion of gender identity. It also instructed the state governments to create measures to ensure the rights of “third gender”/transgender people. Someone’s birth sex does not determine their gender identity, as both are different. While gender is an identity, sex is a biological determiner. Mari Mikkola, among many other theorists, considers that gender refers to men and women based on social aspects such as social roles, status, behavior, and identity, whereas sex refers to biological traits of a person’s body.

Also read: Same-Sex Marriage In India: Unveiling The Marriage Project

Following the legalisation of same-sex relationships, the Arun Kumar Anr. v. The Inspector General of Registration and Ors. case in 2019 was another important step towards inclusivity. It reevaluated and deconstructed the meaning of ‘bride’ mentioned in Section 5 of the Hindu Marriage Act. Arunkumar married Sreeja, a transwoman, according to Hindu rituals and customs. Their appeal for marriage registration was refused by the Registrar of Tuticorin.

The petitioners appealed this judgement before the Tuticorin District Registrar who confirmed the Joint Registrar’s ruling. The District Registrar’s verdict was, then, appealed to the Madras High Court. The court dismissed the fixed meaning of the word ‘bride’ and suggested revisioning the concept of ‘bride’ to include transwomen, intersex individuals, and other transgender people who identifies as women. Therefore, acknowledging multiple gender identities as well as validating marriages beyond traditionally accepted genders.

Source: Bloomberg

The Special Marriage Act was enacted in 1954 in an attempt to uphold the secularity of the country mentioned in our Constitution. The Act was designed to be a piece of legislation that regulates weddings that cannot be solemnized owing to religious traditions, under the Hindu Marriage Act, or Muslim Personal laws. This act was implemented to create consistent legal safeguards for those who desire to marry across their own classes or religions.

The Act contains laws for lawful marriage, marriage qualifications, dissolution of an interfaith marriage, marriage registration, and other rules, to protect their fundamental rights. The Act also intended to avoid the threat of social evils like honor killing, as well as to recognize the rights of children born from such marriages. However, Section 4 of the Special Marriage Act, when interpreted literally, does not mention the solemnisation of same-sex marriage, as the Special Marriage Act was enacted with the legislative goal of allowing the solemnisation of marriages between a male and a female.

Moral policing and restraining sexuality is a way to ensure that a family has a line of pure descendants. Homosexuality, or any other sexual orientation, apart from heterosexuality is a threat to this very notion of purity. Therefore, marriage becomes a mechanism of procreation.

Section 4 clause (c) states that the male must be 21 years old and the female must be 18 years old for the marriage to be legal. It is a known principle of interpretation that the court must proceed to follow the evident meaning of the statute that the legislature has penned.

Also read: 3 Loopholes In The Push For Same-Sex Marriages In India

Marriage has been a heteronormative institution as the society has conditioned it to be, dominant with patriarchal idiosyncrasies. The vehement attempts to protect the sanctity of the institution of marriage, very obviously the heterosexual and patriarchal ones, have always led to violence and marginalisation. The mandate of gender-appropriate relationships is intricately connected to the need for purity of procreation.

Moral policing and restraining sexuality is a way to ensure that a family has a line of pure descendants. Homosexuality, or any other sexual orientation, apart from heterosexuality is a threat to this very notion of purity. Therefore, marriage becomes a mechanism of procreation.

Non-heterosexual marriage, now, offends the already established line of ‘pure’ progeny because the procreation process there might involve scientific intervention, or adoption, which means tampering with the bloodline of the family. A family, as mentioned by Nivedita Menon, is “an institution with a legal identity, and the State recognises as a family, only a specific set of people related in a specific way.”

The family, again, becomes an authoritative institution of hierarchy, inequality, and power play. However, a recent development has been achieved with the Deepika Singh v. CAT verdict where the Supreme Court of India has ruled that the term “family” includes domestic relationships, unmarried partnerships, and homosexual partners. A family might be single-parent for a variety of reasons, including the loss of a spouse, separation, or divorce. This broadens the understanding of the previously limited concept of a ‘family’.

To learn things, unlearning is imperative. The process of learning and unlearning is a continuous cycle. Merely decriminalising same-sex relationships is not enough if they are not given the protection of marriage laws. Marriage must be reinterpreted defying the Union government’s vision of ‘social morality’. An inclusive interpretation of marriage is a prerequisite to encouraging plurality in the socio-political ecosystem, as well as in the regulatory framework.

About the author(s)

Simantini Sarkar is a student, writer, and feminist, as well as a literature and film enthusiast. She has completed her Bachelor’s degree from Bethune College, Kolkata, and her M.A. in English from Savitribai Phule Pune University. She writes for various online and offline magazines and is a budding translator. Simantini is also an aspiring research student. Her interests include topics

related to gender, women, politics, and pop culture.

Legalising the same sex marriage is not good to the our society••