In the endeavour to make India a digital space, we often forget to look back at those who are left behind on the other side of the digital divide. As the COVID-19 pandemic hit the nation, most official and non-official proceedings and transactions shifted to the digital platform. The physical world became emulated into the digital space, but it left behind a large population who do not have access to quality internet or have the means or ability to use it regularly.

Oxfam, in their annual India Inequality Report, brings focus to the disproportionate prospect of progress and advancement that Digital India accentuates. It opens new avenues of opportunities and accessibility that a large section of society, especially those who are financially challenged, keep struggling to catch up with.

The report mentions, “Technology and digitalisation have benefited the privileged but have also been the cause of inequalities, creating a digital divide. This divide largely stems from unequal access to and use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs).”

It repeats the discriminatory pattern of privileging the already privileged ones and narrowing down the already privileged few who get to progress in the increasingly digitised world. It leads to structural and institutional inequality that cruelly and unjustly leaves the privileged few as the beneficiaries of their services.

Also Read: Post-Pandemic Ascend In Gender Divide In Digital India

“The growing inequality based on caste, religion, gender, class, and geographic location also gets replicated in the digital space.” Explained Amitabh Behar, CEO of Oxfam India, to Businessline. “People without devices and the internet get further marginalised due to difficulties in accessing education, health, and public services.”

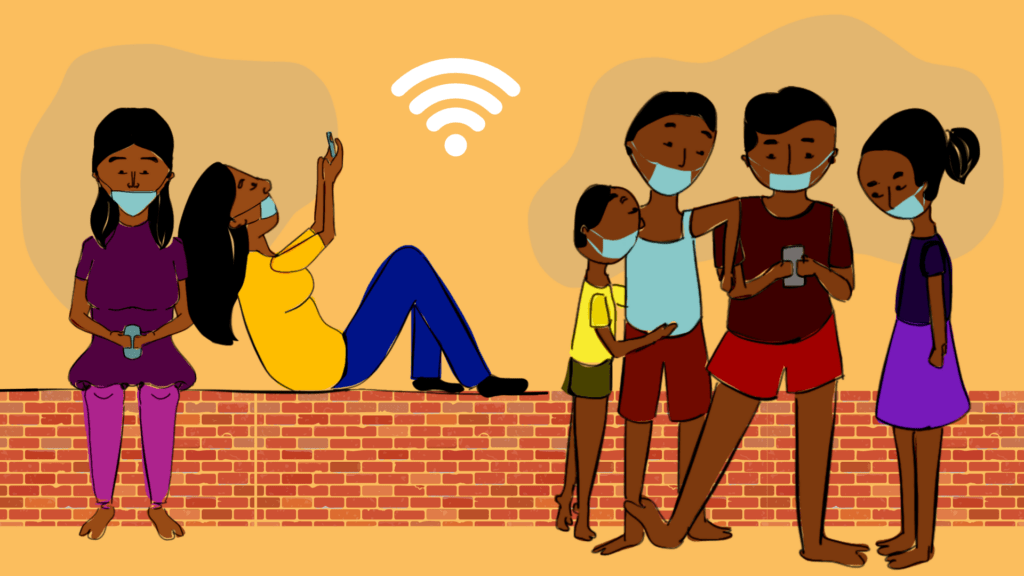

The government needs to ensure universal access to the internet and smart devices before privileging the digital mode of official procedures and transactions. A digital barrier already existed in the country since the inception of smartphones and the internet, as it limited data availability and communicability to a privileged few. Since the pandemic, the gap has widened in every sphere of life and has ruthlessly left behind a large section of people struggling to make ends meet.

In this technological divide, the intersectionality of caste, religion, gender, and ethnicity plays a role in determining who gets access to the narrow premise of the digital world. Whether a person possesses a smartphone, has a stable internet connection and electricity, and is digitally literate is determined by their caste, religion, or ethnic location in society. Such discrimination and unequal distribution of knowledge, information, and means of acquiring it are often replicated within the digital space as well.

Oxfam also makes a detailed study on how the caste background of a person impacts their chances of owning a laptop or a computer, or having a stable internet connection. As of 2021, a person from the General Category is more likely to possess a computer or a laptop than a person belonging to the Scheduled Tribes (ST) category. The gap seems to have widened from 7% since 2018, owing to the adverse effect of the pandemic.

Oxfam has also found that a General or Other Backward Classes (OBC) category person is 4-6% more likely to own a television than a Scheduled Tribe person. However, from 2018 to 2021, the gap between a General person owning a phone and an ST category person owning a phone has dropped from 10% to 3%.

Also Read: E-Education & Access To Information In Lockdown: Digital Divide

In a drastic leap, many essential state services, such as education, health, and banking procedures, shifted to the digital platform exclusively. It is not just exclusionary but also highly discriminatory for the state to make such a shift without universalising data connectivity and accessibility. On this matter, Behar commented that the government should “treat digital technologies as a public utility, not a privilege.”

The report highlights the dramatic digital leap that the nation underwent due to the pandemic. As a result, in professional fields or educational sectors, it becomes quite inconvenient if one does not have a laptop or a computer to carry out the necessary assignments. According to a survey conducted by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) between September and December 2021, 96.6% of the subjects responded that they do not possess a computer or a laptop.

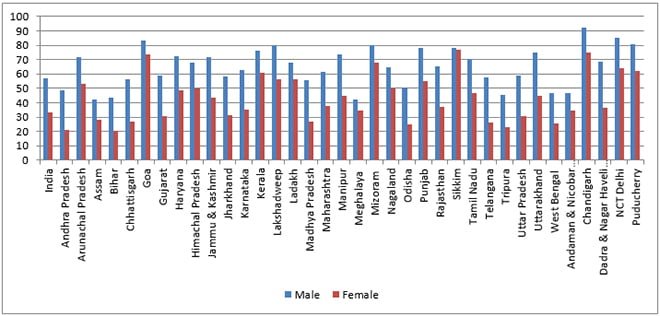

When it comes to internet accessibility and connectivity, gender also plays an important role. The report states that only one-third of internet users in the country are women. It shows that women are 30% less likely to own a mobile phone than men. Studies conducted in this regard also show that digital literacy is considerably less in women than in men. Even with access to the internet, they are unlikely to be able to use it for communication purposes.

With the sudden shift to digital platforms in major educational and professional sectors, women are much more likely to drop out due to inaccessibility. This, in turn, poses a greater risk to women’s education rate and their chances of securing a job. Such a gendered division of internet accessibility can directly contribute to the feminisation of poverty.

The socio-economic background of a person also largely affects a person’s chances of data accessibility. Reports show “each gigabyte (GB) of data costs low-income households (earning less than $2 per day) 3% of their monthly income versus 0.2% for middle-income households (earning $10–$20 per day)”. Cheap internet is given to those who buy data in large quantities. Those with higher income, salaried jobs and higher educational levels would inevitably be the ones who would benefit from such schemes.

Therefore, it becomes evident that data connectivity privileges the financially privileged class within the capitalist structure of the data business.

In terms of data affordability, India ranks 47th out of 110 countries. For an Indian citizen, it is relatively easier to access the internet, but access to devices is disproportionate among Indians, based on their gender, socio-economic background, and caste identity. Women within the ST community are 21% less likely to be digitally literate than men.

The Oxfam report further reiterates, “In a country plagued by high socioeconomic inequality, the process of digitalisation in itself can not be posited as the panacea for the inherent challenges of the physical world. It becomes particularly problematic when half of the population neither has access to gadgets and the Internet nor the technological know-how to move to a digital environment.”

Also Read: Digital Media: Through The Lens Of An Intersectional Feminist

In a hierarchy of privilege, ‘male’, ‘upper caste’, Hindu, and urban citizens belonging to heteropatriarchal households are the ones who are most likely to have data accessibility. Such hierarchy is uniquely intersected by multiple geo-political and social identities of a person. The only possible way to bridge the gap in data accessibility is if the government sanctions data accessibility in every area, in every household as an essential need.

To strive for an ‘inclusive’, ‘resilient’, and ‘sustainable’ digital environment, it is imperative to make equal accessibility the primary concern of every institution. Oxfam suggests that investment in public wifi and community internet access points can greatly improve data accessibility. Besides, state-sponsored investments in the digital industry and continued efforts to control data prices can bring down costs and help ensure more people have access to the internet.

About the author(s)

Debabratee (she/they) is a student of English Literature at Jadavpur University. When they are not found reading or writing, they are found running after their pet dog and cuddling with him. They are avid binge-watcher of all kinds of OTT content and like to dissect and analyse them in their free time.