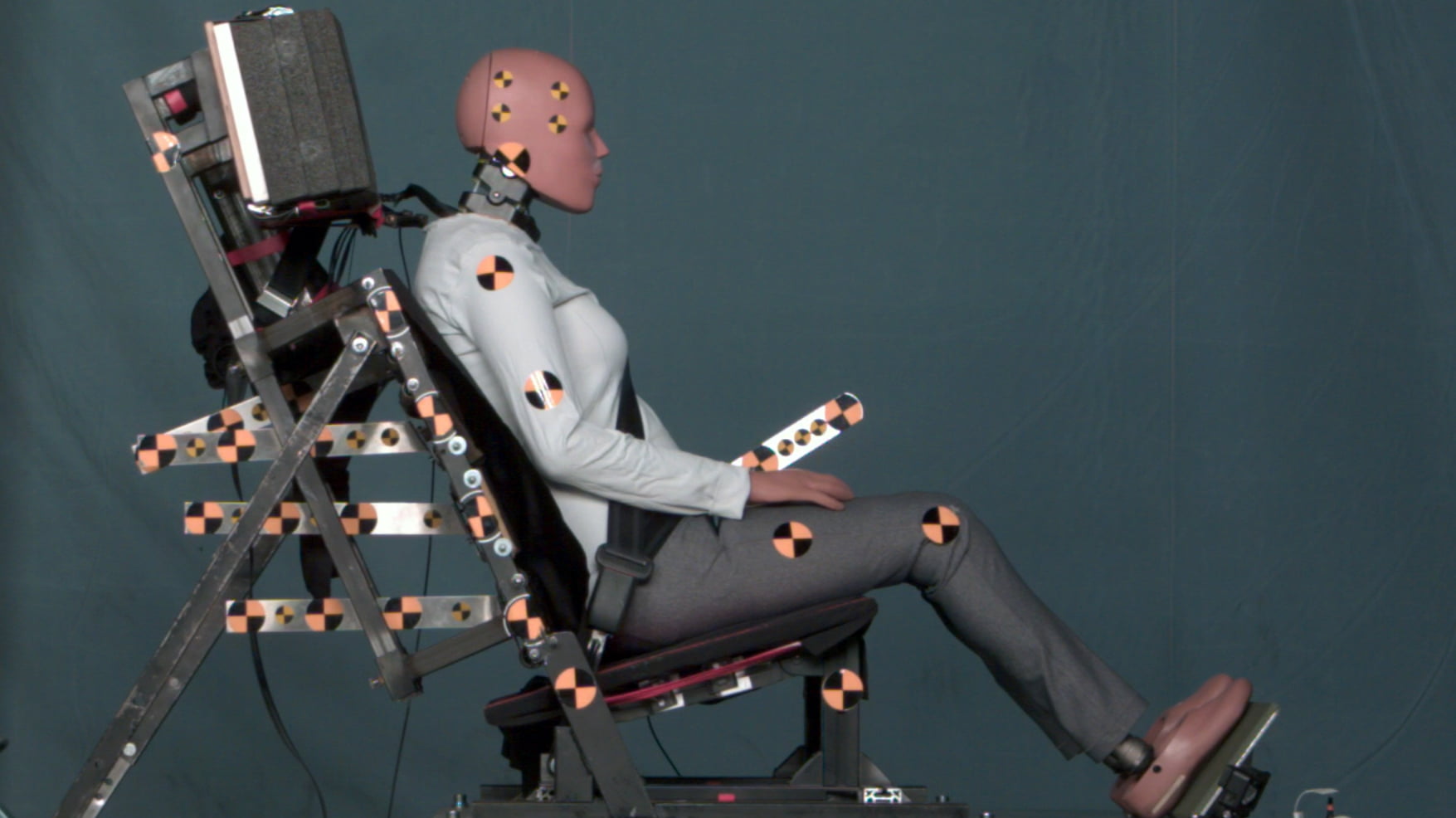

In what is deemed as a breakthrough in safety-testing, researchers at the Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute in Linköping, led by Dr Astrid Linder, have created what is touted as the world’s “first female crash dummy” or what are referred in the technical parlance as the anthropometric test devices (ATD). While, there is some debate on why Linder’s invention be called the first female dummy, when in 2003 Volvo had already developed a pregnant dummy, the answer perhaps lies in the complicated terrain of data,anatomy and social normativities.

Eleanor Holmes Norton, during her tenure on the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure noted “Women have achieved equality on the road when it comes to driving. But when it comes to safety testing to keep them safe on the road, they are nowhere near achieving equality”. Norton’s statement was made against the backdrop of her push to introduce a bill on greater gender-parity in crash test-dummies.

Linder’s female dummy, at 162 cm height and weighing 62 kg, has the same dimensions as an average woman today — this should give more accurate crash test data and help improve vehicle safety for women.The world’s first female dummy’s arrival on the testing-terrain has taken 51 years, it is not just a scientific breakthrough, in many ways it is a social revolution.

A brief history of safety-testing: Origins and evolution

The creation of crash-test dummies owes to the work of USA Air Force Flight Surgeon Major J.P. Stapp who was studying physiology of rapid deceleration in 1949 to make flights safer not only for military pilots but what later took shape in the form of Space-Missions under NASA.

The desire for an understanding of the impact of various simulations on humans without endangering pilots to extreme and often unknown conditions left limited options: that between animals and human cadavers; the former was met with moral concerns from the public and the latter had the added burden of being cost-prohibitive. Against this background, Sierra Sam, the first crash-test dummy, was conceived in 1949 for testing in the air force. However, the data on which Sierra Sam was modelled, naturally drew upon the average male adult who were likely to land-up in the cockpit of a flight.

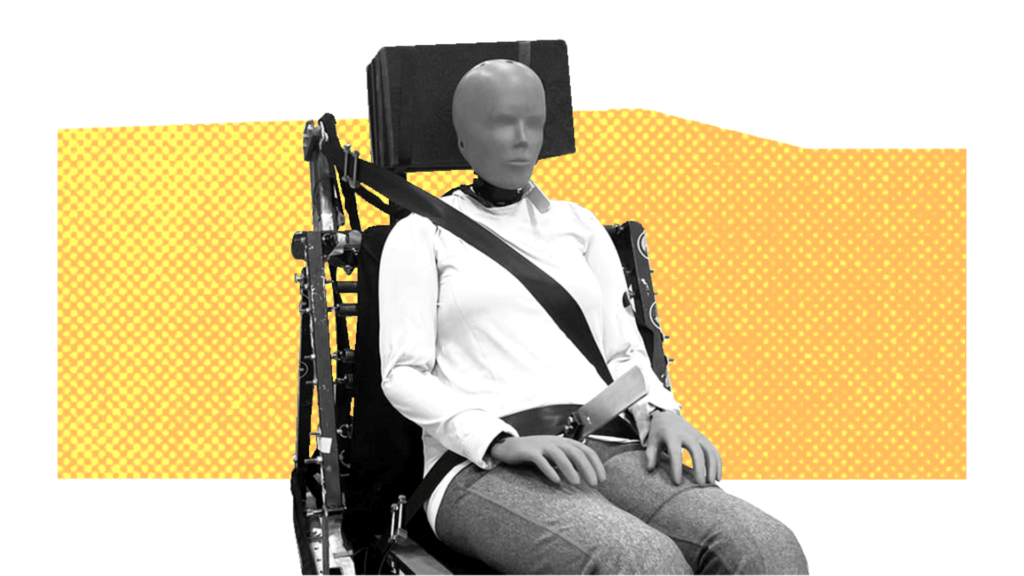

What is also notable about these female-test dummies is that they represent miniaturised versions of male bodies, consequently the anatomical dimensions that differentiate men from women- such as the musculature, torso, hip and pelvis shapes are not incorporated within these models. This has widespread repercussions for anthropometric data collected and employed in not only safety-testing but also ergonomic modifications and applications within cars.

Consequently, the biases of the first ATD were replicated across the prototypes that followed in its wake. The most important of these were the VIP series, called Hybrid I, that standardised the 50th-percentile male — an average man in the 1970s. The next in series were the Hybrid II which included adjustments to spine, shoulder and knee anatomy. A few generations of crash-test dummies later, the 5-foot-9, 171-pound male is still the driver in most front-impact safety-rating crash tests.

What makes Linder’s discovery a scientific breakthrough?

The gender-norms of the 20th century “naturally” dictated that cars for a long time were monopolised for all purposes — commercial and personal, by male drivers. Thus female drivers were by virtue of their absence excluded from necessary safety-testing. As it dawned upon car-manufactures that women do indeed use cars, female dummies were eventually added to some tests. However, their usage was restricted to limited tests such as the Side Impact Crash Test, as while it was believed women used cars, they were only passengers in this rather mystic vehicle.

Also read: Women Steering Ahead: Women Drivers Taking Charge Of The Wheels & Breaking Stereotypes

Yet, even in the limited number of tests that female dummies were used, they were rather unrepresentative of the larger population. They include the Hybrid-III 5F SID-IIs which reflect the 5th percentile in height of women from more than 30 years ago, when they were first developed. At 4-foot-11 and 108 pounds, Hybrid-III 5F is a little lighter than an average 12-year-old girl today. She is also incomparable to the average American woman of today who is 5-foot-4 and weighs more than 170 pounds.

What is also notable about these female-test dummies is that they represent miniaturised versions of male bodies, consequently the anatomical dimensions that differentiate men from women- such as the musculature, torso, hip and pelvis shapes are not incorporated within these models. This has widespread repercussions for anthropometric data collected and employed in not only safety-testing but also ergonomic modifications and applications within cars.

Contextualising this history (or its lack thereof) against findings from a 2019 study by University of Virginia makes the picture further stark — it notes that because men drive more miles and engage in riskier driving such as speeding, not wearing a seatbelt, drunk driving etc. more men than women die in car crashes overall. However, when comparing similar car accidents with belted occupants of about the same age, height, BMI and vehicle year, women are 73 percent more likely to be seriously injured in frontal car accidents.

Additionally, in 2013 National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) found that female drivers and right front passengers wearing their seat belts are 17% to 18.5% more likely than their male counterparts to be killed in a crash. Finally, given that women typically have shorter legs and sit closer to the steering wheel to reach the pedals, it makes them almost 80% more likely than men to suffer severe leg injuries.

All these limited scraps of data underline specifically one point — the anatomical and behavioural differences between men and women have significant outcomes for their survival and long-term outcomes in event of a crash. That, in itself, is a crucial imperative for making a case for female test-dummies. Linder’s test-dummy is not another miniaturisation of existing male dummies but rather an attempt simulating a real-female analog, with not only anatomical modifications but also sensory additions aimed at collecting some targeted data on low-severity, rear impact-collisions that tend to be much worse for women than men.

What makes Linder’s work socially revolutionary?

Eleanor Holmes Norton, during her tenure on the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure noted “Women have achieved equality on the road when it comes to driving. But when it comes to safety testing to keep them safe on the road, they are nowhere near achieving equality”. Norton’s statement was made against the backdrop of her push to introduce a bill on greater gender-parity in crash test-dummies. As reassuring is Norton’s push for bringing in gender-parity in crash test-dummies, it is accompanied by the troubling realisation that even if Norton succeeds, and regulators mandatorily begin testing with female dummies, it would take at least a decade to include females in test data.

The patriarchal mandate curates a social landscape where women’s existence is either not recognised, if recognised it will be actively invisible and if forced to be recognised and visible, it will be probably transformed into an accessory. This translates into an exercise of silencing and purging her presence out of all domains, including that of data. Consequently, disciplines like history, sociology and anthropology have for long arced a narrative where women do not exist in their own right. Their evaporation by the social sciences is mirrored by biological sciences — modern women then live in a world of data poverty, leaving them susceptible at all corners to death and disability.

What embarks in the 21st century is a depressing teleological cycle—data-poverty as a product of historical biases while increasing female vulnerability on one hand; the inertia about breaking the patterns on replicating dissimilar data (for ex. modelling female anthropometry on male data) further compounds the danger. Womanikin and Linder’s work in this context are not only defining a new scientific paradigm but also a social one.

For instance, a 2017 study looked at data from more than 19,000 people experiencing cardiac events and found that only 39% of the women received CPR from strangers in public vs 45% of the men, and that men’s odds of surviving were 23% higher than those of women. Similarly, Caroline Criado Perez has shown that while every year, 8,000 people in the UK die from work-related cancers, unsurprisingly, men have been the natural focus for most cause-finding research. She contrasts this with the significant rise in breast cancer over the past 50 years and underlines the failure to research female bodies, occupations and environments to collect data that may highlight the causative factors at play.

Also read: Stop Teaching Women Only How To Cook; Teach Them Driving!

Rory O’Neill, professor of occupational and environmental policy research at the University of Stirling, adds, “We know everything about dust disease in miners, You can’t say the same for exposures, physical or chemical, in ‘women’s work’.” He adds that the danger is compounded, given that cancer is a long-latency disease and even if we started the studies now, it would take a working generation before we had any usable data.

What embarks in the 21st century is a depressing teleological cycle—data-poverty as a product of historical biases while increasing female vulnerability on one hand; the inertia about breaking the patterns on replicating dissimilar data (for ex. modelling female anthropometry on male data) further compounds the danger. Womanikin and Linder’s work in this context are not only defining a new scientific paradigm but also a social one.

Female test dummies: End game or a new chapter?

It is tempting to think that a revolutionary design that the Swiss team has presented ends the woes of female safety in cars on roads, however, the page-turner is only the first chapter in a long-journey for making driving safe for women.

Also read: Our Gendered Streets And The Gang Of ‘Unbelongers’

Studies show that besides the anatomical and behavioural differences that impact survival and injuries in a crash, differences in outcome for men and women also emanate from the interaction between vehicles, for instance women tend to use smaller and lighter vehicles viz a viz men. The journey of making roads safer for women requires a combination of social and scientific perspective-taking. On one hand it requires legislation that mandates gender-parity in testing to reduce the gap in available data, on the other hand it requires a more holistic socio-scientific evaluation of the multi-pronged factors beyond the simplifications that a dummy can afford to make driving safe and secure for women.

There are clear lessons for India too — as we ramp up our infrastructure, there is a pressing need for timely intervention in engendering what is being built so the future truly belongs to all citizens, otherwise we may just have spent billions in uplifting the uplifted.

About the author(s)

Harshita is a postgraduate student at the University of Delhi. She is interested in areas of Gender, History and Social History. Her research interests are at the intersection of gender, power and social categorisations.