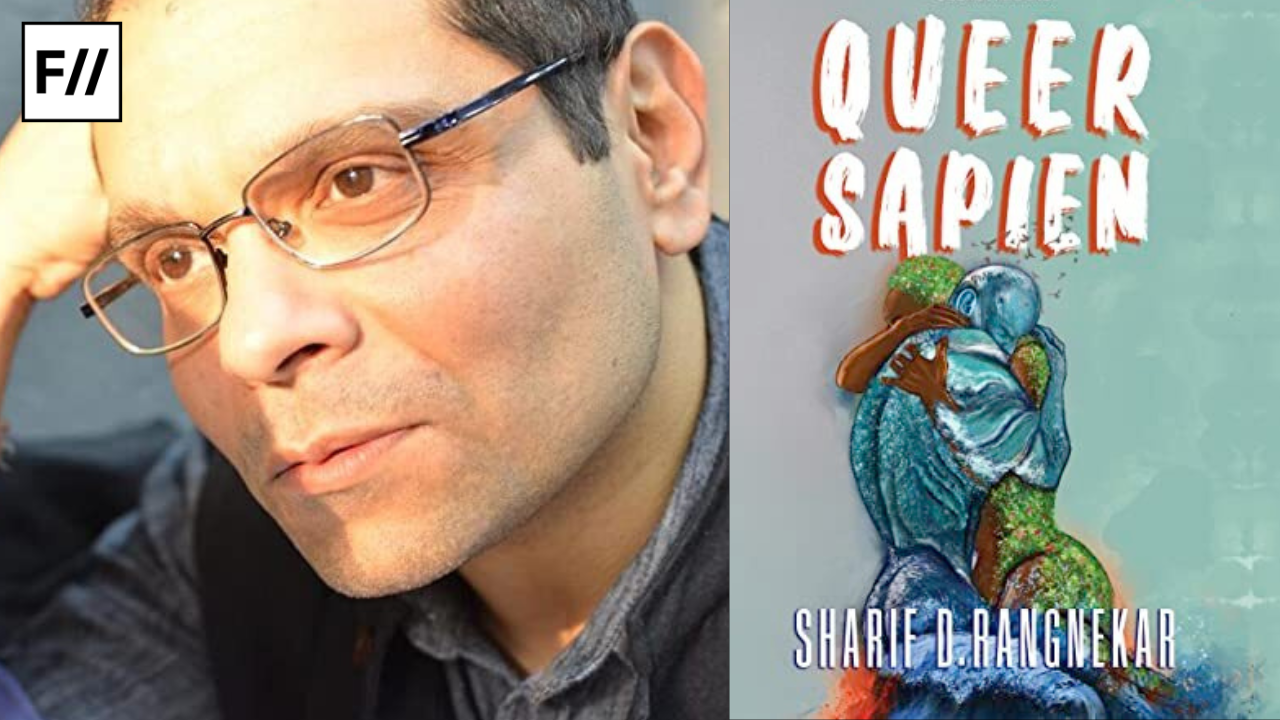

Sharif D. Ragnekar’s Queersapien is a worthy attempt at tracing the life of Sharif and exploring how queerness is embedded in multiple forms. However, the way the book has been marketed about queerness being encompassing is something that the book drastically fails to live up to. The synopsis of the book reads “…is a searing and raw reflection on life, media, neoliberalism, politics and the inner self…like queerness, this book cannot be thematised into a box”.

Sharif says about Indian shopping for jeans and clothes that didn’t match the conservative cultural ethos – “it didn’t matter if there were knock offs or fakes.” Ultimately, the book has a lot of uncalled commentary on culture in general, which also places a certain level of morality and respectability at a higher ground, or at least it attempts to. Calling women who hold traditional understanding of sex as merely products of arranged marriages also hides the ways women are coerced into marriage and denied from having education or career.

In the preface titled The Queersapien I am, We Can Be, Sharif marvelously takes us through the different forms that queerness can take, but one needs to ask if that comes at the cost of simplifying the idea of intersectionality. While the book is solely from the experience of Sharif as a gay man living in India and trying to find a better, free-er gay life in Bangkok, the tone of queerness it assumes is universalising in nature, which is antithetical to the idea of queerness itself.

The book as an account of Sharif’s life is also messy and spread all over. For instance, the opening chapter Judgement deals with the nuances of the written order from the Indian Supreme Court that read down Section 377. The chapter begins with the Judge Indu Malhotra’s comments about history owing an apology to the community.

Also read: Queer Politics In India: Towards Sexual Subaltern Subjects By Shraddha Chatterjee | Book Review

Sharif then takes us through the myriad of meanings that queerness means, especially for him as a gay man in terms of liveability; and explores what the judgment signifies. It also makes the sharp and rare comment about there’s more to queer lives in India than same-sex marriage especially the need of laws that protects us. Unfortunately, the rest of the chapter does disservice to the queer rights movement in India, and omits the contribution of trans persons to the movement.

When discussing about sex workers, Sharif says, “however, I had the privilege and power to shift my eyes on someone else” which certainly feels discomforting to say the least. There is some discussion of gay culture like disco as the ‘gay music,’ appearances, engaging in drugs, the way falangs behave in Thailand, and more.

In the next series of chapters, Sharif explores the differences between the ‘gay culture’ of India versus Thailand, which sits at the center of his work. These are the observations about cultural differences which marks this work on queerness peculiar from other similar narratives. There are the usual comparisons to Delhi or Mumbai and how Thailand as a space is different but more than that there is emphasis on how it is different for Sharif as a gay man, as there’s a much larger sense of freedom in being who you are. Taking us through the chaos and the congestion, the chapter dives into the streets of Bangkok, followed by another that does the same for Pattaya, which is also called ‘sin city’ or ‘sex city’.

This is where the most significant critique of the book lies as there are multiple instances where Sharif is merely acknowledging his privilege but it comes off as being overtly judgemental during making observations. For instance, when discussing sex workers, Sharif says, “however, I had the privilege and power to shift my eyes on someone else” which certainly feels discomforting to say the least. There is some discussion of gay culture like disco as the ‘gay music,’ appearances, engaging in drugs, the way falangs behave in Thailand, and more.

There are many unnecessary comparisons driving a point about the cultural difference. Sharif says about Indian shopping for jeans and clothes that didn’t match the conservative cultural ethos – “it didn’t matter if there were knock offs or fakes.” Ultimately, the book has a lot of uncalled commentary on culture in general, which also places a certain level of morality and respectability at a higher ground, or at least it attempts to. Calling women who hold traditional understanding of sex as merely products of arranged marriages also hides the ways women are coerced into marriage and denied from having education or career.

To cite an example, Sharif says, “I could never comprehend how difficult it may have been to offer his body, perform with passion and do all that it took to bring a smile on the face of a client.” Within the same breadth, Sharif also makes a disrespectful comparison citing- everyone has a potential to love irrespective of their profession (while talking about male sex workers in Thailand) because even murderers, hate-mongering criminals, and ruthless money-makers have a soft side.

Another critique of the book that’s worth mentioning is that after a point, Sharif’s story becomes more about Sharif narrating the life stories of people he met in Thailand, of his friends, and of his family. On one hand, this work as most of them also made it through life facing difficulties and at the end, they were tied together by love. Having said that, there is nothing ‘queer’ about these narratives and once again, the comparisons that Sharif makes to ensure the validity of his experiences seems futile, mostly because they miss the point that queerness being a hundred other things, is also unique to every person in the world. Having mentioned in the beginning,

“Queerness, however, is not about turning back in time; it is about turning things around,” Sharif’s work doesn’t hold up to it.

Even the bits that shed light on sex economy and the cultural differences between India and Thailand in terms of sex have some references to history, research reports, and data which demands for a deeper exploration than mere mention of the same. Perhaps, there could have been footnotes to expand on them and their significance further.

Also read: Book Review: Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practices Of Queer Diaspora By Gayatri Gopinath

Another issue with the book is the language that Sharif has employed towards sex workers in general. While there’s a sense of curiosity at someone experiencing sex work in a queer context for the first time, yet, for a book that talks about dignity and equality in terms of love and rights regardless of sexual identity, there is a lot to improve upon.

To cite an example, Sharif says, “I could never comprehend how difficult it may have been to offer his body, perform with passion and do all that it took to bring a smile on the face of a client.” Within the same breadth, Sharif also makes a disrespectful comparison citing- everyone has a potential to love irrespective of their profession (while talking about male sex workers in Thailand) because even murderers, hate-mongering criminals, and ruthless money-makers have a soft side.

On one hand, the exploration of finding liberation, love or settling down in Thailand offers a unique (albeit privileged) perspective on what it means to find other avenues of exploring queerness and being free in the real sense. It all comes with a heavy judgment on others, often with a disrespectful tone towards people from different classes which is disguised as one being biased on observations. This is an issue because what Sharif explores becomes more about the optics and visibility and how he views specific people’s lives, rather than a true exploration of what makes his life journey queer.

When the book mentions about Sharif’s famous friends from the queer community or hints at the struggle of someone being denied the choice of studying liberal arts at Ashoka University, I could not wonder how this account is knee deep in privilege.

The few places where Sharif makes sensible points include the lack of policy making in corporates for inclusion of queer people, observations about cultural differences between Thailand and India and their views on sexuality, critique of the Indian culture of hostility towards other gender identities, observations about how the law cannot resolve personal and cultural realities, and Sharif’s experience of being closeted versus ‘out and proud’ in a professional setting.

In the chapter titled To Love is A Battle, there is again an overemphasis on Sharif’s family and their backstory which seems unwarranted for a book based centrally around the idea of queerness. The only decent understanding around queerness is offered in a short excerpt about the idea of ‘choosing families.’ Baring this, the chapter is a dry commentary on Indian culture being sexist and homophobic. In the chapter that follows, there is a tracing of Sharif’s Brahmin lineage with rare emphasis on how pride is more than one’s caste identity. But again, the comparison to freedom fighters seems uncanny as fighting for the nation is vastly different from waging a war against the same nation for demanding equal rights.

When the book mentions about Sharif’s famous friends from the queer community or hints at the struggle of someone being denied the choice of studying liberal arts at Ashoka University, I could not wonder how this account is knee deep in privilege. And even with the mentions of queer activists like Dhiren Borisa, Jyotsna Siddharth, and Dr. Aqsa Shaikh . Sharif has failed to learn from their experiences around how to weave a life around queerness into words. More than that, this is based on a pedestaling of queer people which harms the narrative of normalising queerness or finding universality within the same. Queer theorists like Halberstam have also warned against the idea of upholding queer people in higher regards so as to make them seem normal.

Leaving aside a few personal anecdotes and inspiring narratives centered around love, freedom, family and cultural differences, Sharif D. Rangnekar’s Queersapien is a lackluster attempt on redefining queerness replete with uninformed comments, unnecessary comparisons, and a disservice to the diverse and intersectional queer movement in India.

Also read: 5 Indian Books With Queer Protagonists You Need To Read

While the book absolutely works as a gay man’s story to look for deeper meanings of queerness through his life experiences, the universalising tone stands at odd with the privilege that Sharif holds, especially one that allows him to explore queerness and ‘gay life’ as a tourist in Thailand, which is certainly not true for most of the queers. At the same time, the emphasis is inadvertently on finding queer life through escapism or through assimilation but lacking a self-reflective account.