Editor’s Note: FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth for February 2023 is Love In Post Modern India. We invite submissions on this theme throughout the month. If you would like to contribute, kindly refer to our submission guidelines and email your articles to shahinda@feminisminindia.com

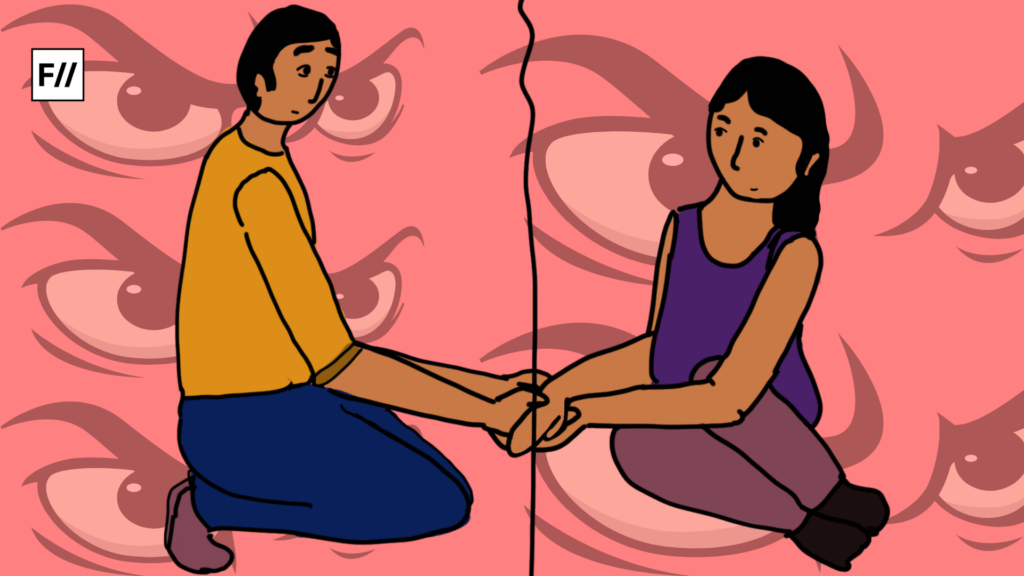

A senior of mine (who would like to stay anonymous) like every other nervous bride-to-be after years of a well-thought marriage with her boyfriend of another faith and the dream that seemed beyond reach made her have this joy along with mixed feelings and questions – whether she would fit in the new culture or not? Will the family truly accept her? Will her husband-to-be expect her to change her identity, her faith, and her culture? Will that change be sudden through force or subtle in terms of rituals? Nonetheless, she brushed aside such apprehensions.

As she mentioned they were just the mere apprehensions of her anxious mind. After all, she said that her husband-to-be had never asked her to be any different from who she was. In fact, according to her, their religious and cultural differences were what brought them together – there were no disagreements, only dissimilarities. We humans sometimes, fail to detect that difference and consider that unusual as ‘unacceptable‘. There are a number of examples of interfaith love and relationships around these lines like my senior’s story.

Humans desire several things. Some are our ‘wants‘ while the rest are our ‘needs’. According to Maslow, a famous American psychologist in his Maslow’s hierarchy of needs ranks human needs on the basis of our urge to fulfil them. In this the “love needs” which include striving for “love, affection and belongingness” rank right after our basic physiological and safety needs. These needs can be fulfilled within general relationships with romantic partners, family or friends. in groups Etc. That’s why we claim that humans are ontologically social beings.

Also Read: Love In India: Bridled Or Unbridled?

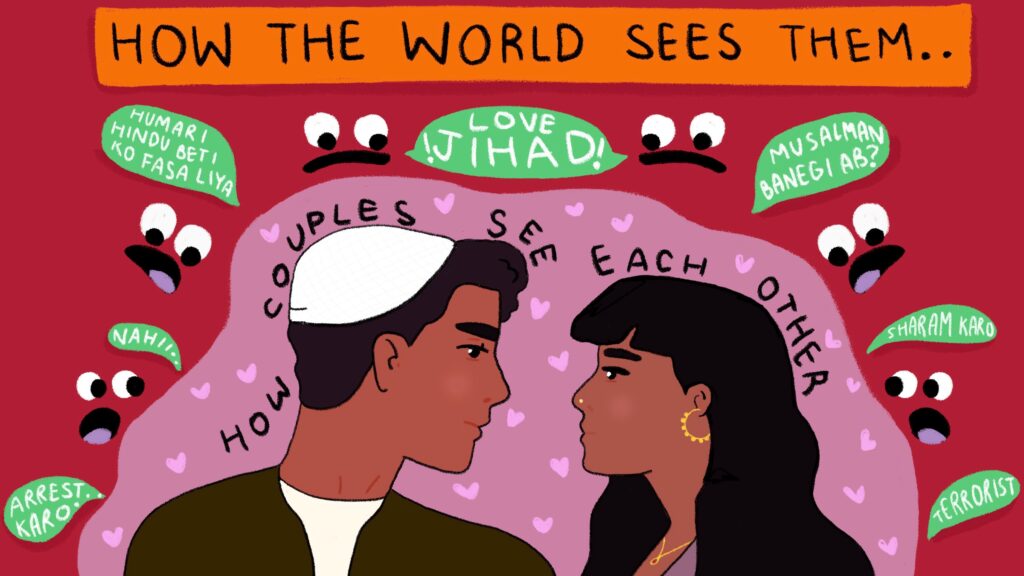

Love transcends all socially set institutions, such as religion, family, marriage, and bearing children, as morally deep-rooted in our sociological context of religion. However, in recent years, our country’s politicians have weaponised love for political ends. Today, we refer to this weaponisation as ‘love jihad‘.

From big celebs like Shahrukh Khan to Priyanka Chopra, many married partners of different faiths. However, people claim that it’s easier for the higher income groups to marry beyond the lines of faith but it’s equally challenging both economically as well as socially for people of lower income groups to marry beyond such boundaries. But does that mean love is so weak? Love is so fragile that it can’t really cross these realms.

Love beyond the boundaries of social institutions

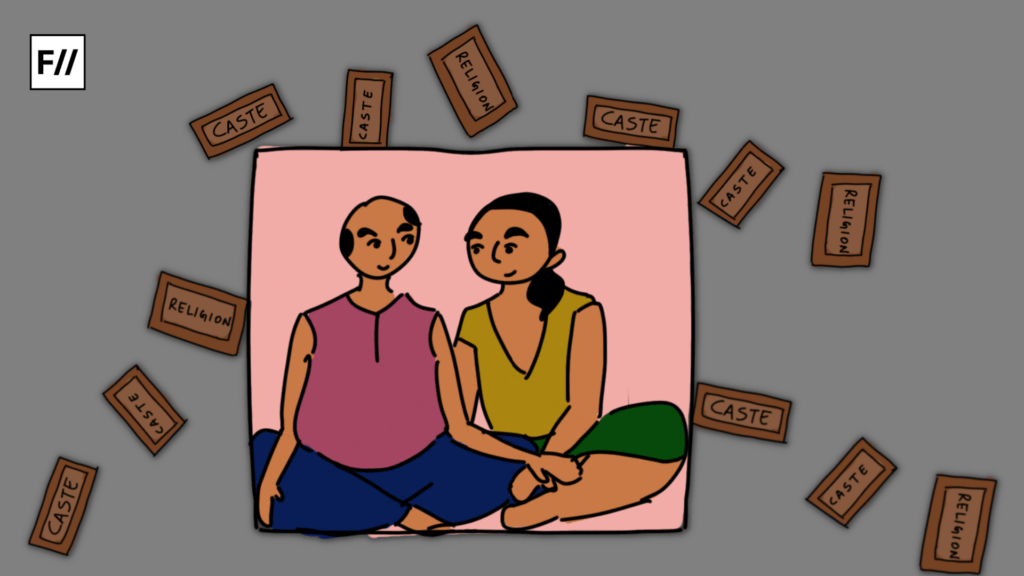

Endogamy has been viewed as a social norm in Indian arranged marriages for a long time. As a result, our country’s cultural diversity has been tarnished. It is just a matter of fact to show unity in diversity in films and nothing more. However, in many quarters of our country, the opponents of this idea of love jihad are resisting this divisive narrative of hatred and are actually giving love a chance. The India Love Project started by journalists Priya Ramani, Samar Halarnkar and Niloufer Venkatraman was an online project initiated on October 20 to explore romantic love and marriage outside the shackles of caste, faith, gender and ethnicity. When this trio started the page, they returned to their day jobs, while anticipating a submission every week for this page. But ever since the launch, the page received a new story every single day.

This constantly provides a certain hope for transforming the normative ideas around love into more than heteronormative, intra-caste, and intrafaith concepts. However, cases of the spike in harassment against interfaith couples by vigilantes have unfortunately ruined the picture.

Also Read: In The Name Of Cow: Love In The Time Of Fascism

The very idea or perspective of two free souls deciding and making their future choices of exploring their lives together and understanding their differences in each other in a relationship has and should always be there. Isn’t it they who get to decide and not us as a society? Who are we to question after all? Love has and will always exist beyond all realms and boundaries of our socially set norms. Sustenance of any sort is a social situation in which any relationship grows. As a growing society, we must accept and tolerate differences, tolerate changes and accept each other’s identities as they are.

Till now, we mostly believe and only experience difference as a power game (whether we try to understand it through our colonial past, partition history or our intra-cultural caste hierarchies). There are new societies emerging all over the world every day. All are in the process of learning to live with their differences. Love that thrives for equity is best than the one thriving for equality. Looking at this process, we need to rise above and think much beyond our specific caste, religious or cultural identities and much more.

What do the statistics suggest?

Among a fifth of India’s 1.27 billion people identify themselves as belonging to faiths other than Hinduism. Hindus account for 80 per cent of India’s population still this fear-mongering of the populational influx of other communities arises. According to Pew Research, around 1% of all Indian Marriages are with spouses who were raised in a different religion. Even though, both society and the state are policing people’s relationships we see how people make a choice and marry beyond the boundaries of such social institutions. The political polarisation of religion ultimately leads to the gaining of votes on the basis of religious propaganda and hate against a particular community.

People are mongered with irrational insecurities regarding their faith. They believe that they have the power to control emotions like love, and politicise people, especially women and their power to choose whom they want to love and be with. This politicising of women and their relationships comes from a very patriarchal standpoint where men of a particular religion consider themselves as authority figure who try to control women’s choices rather than providing them with a space to be able to live with the freedom to choose for themselves. Because every community considers a certain sort of ‘intent of protecting their women, as a matter of fact, to equate it with protecting their community’s honour’. All in all in this we fail to realise that love as a concept stands beyond all these boundaries of different social institutions.

The love jihad law

Currently, around 11 states have laws against ‘love jihad‘. This legalisation of force against love to date is considered the legalisation of the ban against forced conversions. However, who knows or monitors whether the person converting is forcefully or lured to change their religion and does that under pressure or under willingness is another subject to be investigated and studied in itself. Some states, like Himachal Pradesh, enacted these laws in 2019, while others like Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh did around 2021, for their old ‘Freedom of Religion’ Acts, aimed especially at preventing Hindu women from marrying outside the faith.

Others like Orissa (1967), Chhattisgarh (1968), Arunachal Pradesh (1978) and Jharkhand (2017) have statutes to control religious conversions, however, those Acts do not enter the private sphere of marriage. Apart from this ‘love-jihad’ law, Indian national law recognises interfaith and intercaste marriages under a provision called the Special Marriage Act of 1954. But the process is long, painful and rigorous for many. They have to establish residency, notify local officials of their intention to marry and observe a waiting period — during which anyone is allowed to lodge an objection against their marriage. All the objections must be investigated, which takes time.

It is still up to the ‘so-called protectionist groups‘ to deliver love and justice to the children when their parents are supportive. Today, we realise how institutions like marriage are entangled in this politics of communal hatred against some specific communities just to suit the political interests of authority. However, if people rationally counter this fear mongered for political gains, then certainly love above all has the power to change the way people think about these enforcing ideas.

About the author(s)

As an independent journalist, writer, and aspiring documentary filmmaker, Stuti covers about social and political issues. Interested in development journalism she also highlights issues on human rights, gender, education, unemployment, law and others. She aims to start her own news media initiative in the future to transform the way development is covered and discussed in the news.