Trigger Warning: Mention of rape

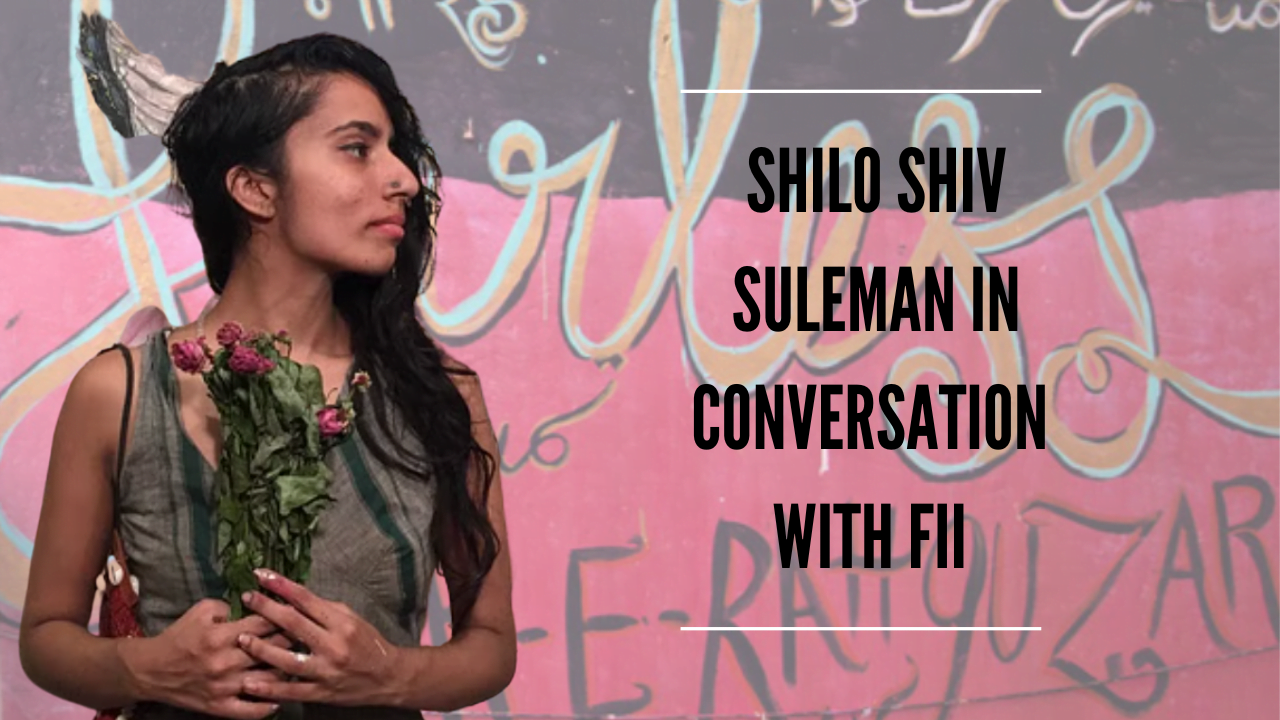

Shilo Shiv Suleman is an Indian artist, illustrator and activist. She founded The Fearless Collective, an art collective which employs the use of participatory art in public spaces, in 2012 as a response to the patriarchal narratives surrounding gender-based violence, that were being circulated within the Indian media. This led her to be felicitated with the Femina ‘Woman of Worth‘ award in 2014 and the New Indian Express Devi award in 2015.

In Conversation with FII, Shilo Shiv Suleman talks about her initial years of work, the challenges she faced and her personal identity.

FII: It has been a decade since you founded The Fearless Collective in 2012 after the Delhi gang rape case. Would you like to share what motivated you to start the collective?

Shilo: Ten years ago, when the Nirbhaya case happened in India, one woman’s story somehow became a vessel to contain the narratives of thousands and thousands of women. We were all there on the streets with our fists raised, mourning the violation against a woman, but simultaneously acknowledging our own moments of grief. As we were unfolding each other’s stories, there was not only a catharsis but a tremendous amount of alchemy. There was healing, there were people coming to terms with their own hidden parts, like hidden wells inside of them, that they hadn’t revealed to each other, perhaps ever. As I would look around people that I loved—from family members to friends—they were all revealing their wounds to each other, in perhaps the most authentic way that I had seen in many generations of Indian women.

Parallely, while every newspaper you picked up at that point was reporting violence against women, the mainstream narratives didn’t hold any space for healing. We all talk about change and revolution and protests, but actually, for anything to move, it has to move from a deeply internal place, it has to be this interior alchemy that then leads to larger revolutions. Planets circling around the Sun have a deep interior sense of gravity. For me, hearing the stories of people I knew and didn’t know was that deep space of gravity.

FII: What do you think has changed in Indian society in terms of how safe women are after all these years and how has your Collective’s work evolved as a result of that?

Shilo: Now, ten years later, I don’t know if I can speak for what happens on the streets in India anymore, or even necessarily what has shifted or not, but what I can speak for is definitely what has shifted inside of me, and the way that I view public space in the country. We, through The Fearless Collective, try to be there for communities that are unable to fearlessly view public spaces. When we paint a mural or create a public monument, we turn up so radically in love with ourselves, that there’s no space for anybody else’s hate.

Also Read: FII Interviews: The Short Haired Brown Queer Prarthana On Being Queer In India

The way Nirbhaya chose to reveal her name, we choose to reveal ourselves, we choose to make ourselves incredibly visible when we’re not hiding, we’re not ashamed. And we’re definitely not victims of our own narratives. Instead, we hold the threads of our own stories. It’s not that we’re not afraid; we are afraid. But we choose to be able to combat our fear with love, beauty and imagination, rather than buckling to our fears.

FII: How has growing up half Hindu, half Muslim shaped your personal identity?

Shilo: I was born Shilo Shivanandan, which is my father’s name. At some point, I decided to change my name to Shilo Shiv Suleman, which is my mother’s name, because I was being brought up by my mother. So, I said, “Why not acknowledge the matriarchy here? Why not acknowledge that my mother is a single mother who has birthed me, who has brought me into existence?” But I remember six years ago, my mom sat me down and said, “Shilo, you don’t understand. If you have a Hindu name on your passport, you keep it. I may have taken care of you, I may have raised you. But there’s no reason for you to have a Muslim name.”

I had thought nobody cares what name you have in this country. Skip to four years later being in Shaheen Bagh. Well, millions of people are potentially stateles because of the names that they have, and because of all their paperwork.

FII: Would you like to talk about the intersections between your Hindu and Muslim identity?

Shilo: I will definitely say that sometimes I have a tendency to be able to imagine that we can view identities in very fluid ways. Me being half Hindu and half Muslim is the same way that multiple mystical identities have been formed at the threshold of Islam and Hinduism, there have been no separations. Pilgrims would go from one destination to another and what is sacred is really what we have to offer, regardless of our religious identity. But, the reality of the situation is that right now we live in very politically tense times when it does matter what name you have on your passport.

FII: Are there any experiences or moments that stood out to you while you were travelling to and working in different countries in South Asia?

Shilo: At first, we received an invitation to Nepal and I realised that our methodology works over there as well—these processes of self-representation weren’t just an Indian thing, they actually worked in a universal way. Then we started to work across the world, went to seventeen or eighteen different countries, and painted over fourteen murals. Pakistan, in particular, for me, was a very, very interesting trip because if we’re talking about fear and national trauma, that is still an ongoing story. It is a reckoning, like when we hear people tell each other stories about partition or even what Muslim identity means in India right now.

So, for me to be able to go to Pakistan and paint three murals there was one of the most fearless things I’d done. One of our collaborators, who was helping us with visas, was shot in Pakistan a few months before I arrived there. It was perhaps the first time that Indian artists were working on the streets in Pakistan and painting murals. Faces were blacked out of people within a few hours of painting the mural, and none of our Pakistan murals remained because we were painting images of women on the streets and they were instantly torn down. So, for us to even make the attempt to paint a feminist mural in Lahore, to paint the transgender mural in Rawalpindi, to paint with children affected by gang violence in Lyari in Karachi, even that was a radical act.

And since then, I’ve seen a lot of incredible movements around street art occur in Pakistan. But when I went there, the only street art that we were really seeing was images of Jinnah being painted on the street, or perhaps some graffiti writing, but there was no real political street art before Fearless made its footprint there. So it was really like a moon landing in a sense.

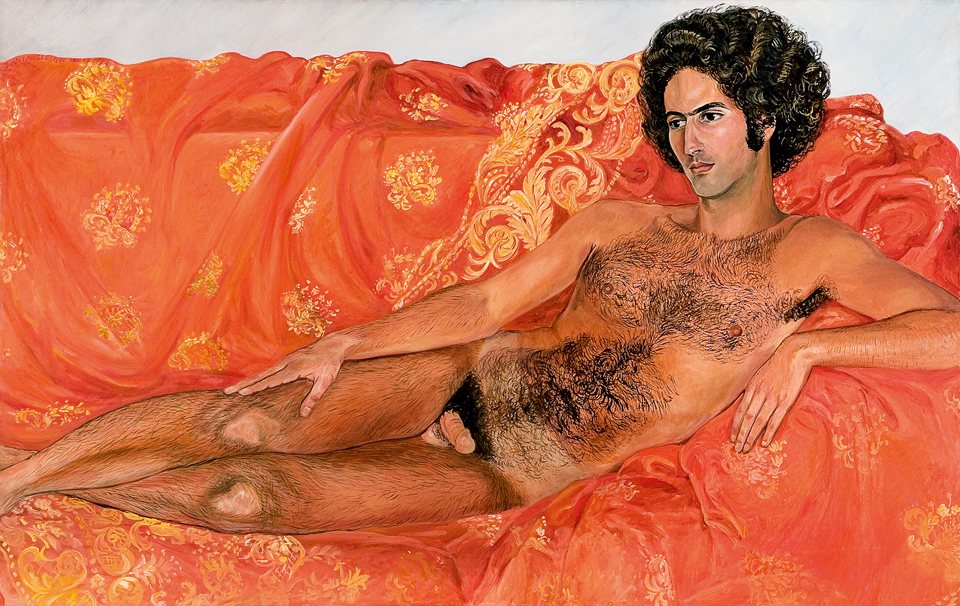

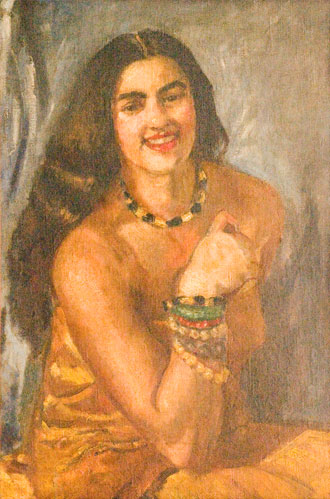

FII: Your mother, Nilofer Suleman, whom you mentioned in your response, is also an extremely famous artist. How have your interactions with her throughout your life shaped your own art?

Shilo: My mother’s name is Nilofer Suleman. Nilofer is a blue flower and Suleman, a mountain range. We’re very different from each other, despite us both being artists, and both being keepers of beauty in many ways. She’s very meticulous, and she spends four months on a painting. And her work is also not outwardly political, but it’s very inwardly political. And with my work, I can spend four days on a sixty-foot mural, and be like “Okay, I’m done, bye“. So I tend to be a lot more broad strokes, I tend to be a lot more rebellious, and vocal. But my mother has a very different approach to identity and politics, an equally powerful approach.

Because while with me, a lot of the fearless work is about reclaiming public spaces, making monuments for different communities who are on the margins, with her work, it is a remembrance. She remembers the body language, the nuance, the poetry, the iconography, the calligraphy, and the beauty of these communities. So with her work, it’s not so much about banging a drum on the street as much as it is about archiving and remembering the histories of these communities who are no longer remembered in the same way.

Also Read: FII Interviews: Ikroop Sandhu — Author Of “Inquilab Zindabad”

FII: You often talk about the theme of ‘feminine power’ or simply the ‘feminine’ in art and culture. What does the feminine mean to you when it comes to your own artistic creations?

Shilo: Despite not growing up with my father, the mythology, the imagery, the iconography of Hinduism, and also the spectrum of the feminine that exists within Hinduism, for me was always very fascinating. So there is an automatic kind of linkage for me because the myths are so beautiful and they’re also non-binary. With definitions of the feminine, I think the point is not to define it, because the more we start to define it, the more we find ourselves in binaries, roles and expectations.

The idea is less to define and more to recognise that there are dualities and multiplicities in the world, and it’s a spectrum of multiplicities that exists within cultures, within our own bodies, within the spirit, and within energy. What one culture defines as feminine could have a very different definition somewhere else.

About the author(s)

Upasana is a master’s student at SOAS, University of London where she is pursuing a degree in South Asian Area Studies. She is an avid blogger and a film reviewer which means that she is currently struggling to balance her time between Netflix and her grad school commitments. When not reading, writing or binge-watching something, she can be found having deep conversations with her close friends or complete strangers about the most random things under the sun.