Ankur, a 1974 film directed by Shyam Benegal, starts with an opening scene of its female protagonist Laxmi, played by Shabana Azmi, taking part in a religious procession to their local deity’s temple. We see a village lady offering a seedling to the deity while Laxmi utters the word Pandlu, meaning fruit, as she asks the deity for the gift of a child. The title of the film, Ankur, meaning seedling, sets the film’s theme, which explores the birth and predicament of a child (seedling) born outside the union of caste endogamous marriage.

Caste hierarchy and the labour it extracts from the oppressed castes is the running theme of the film, which the male protagonist, Surya, skilfully portrays. This modern-age university-going hero does not believe in the religious dogma of caste Hindus and has misgivings about taking up his landownership business. He refuses to get married to a child bride and wants to pursue higher education but eventually gives up both his demands under pressure from his father. He moves to the village to take care of his land, leaving his young wife behind, who is yet to reach sexual maturity.

In the village, Surya meets Laxmi and seduces her, a Dalit woman from the community of Kumhars (Potters) who works as a cleaner along with her husband with a speech and hearing disability and an alcoholic, Kishtayya, in his ancestral home.

The film excels at breaking free from the old Indian cinematic tradition of the one-dimensional, menacing and evil portrayal of the casteist landlord’s son by fleshing out Surya’s character as a lost, aimless youth powerless in the face of his father’s patriarchal authority. Throughout the film, he repeats the sentence, “I do not believe in this caste crap“.

He even asked Laxmi to cook food for him instead of getting his meals from the village priest’s house, a sign of his “virtue” and “caste blindness” that he inculcated from his urban-university education. Nevertheless, as the film proceeds, it becomes clear that Surya is no anti-caste warrior; he has no interest in challenging the status quo and enjoys the privileges of caste hierarchy while denying its significance.

Also Read: Mandi Film Review: A Marketplace Of Empowerment

Caste as a form of extracting labour

We see many farm labourers working in the field owned by Surya and his family during the film. However, their faces are always invisible to the audience and Surya, as the camera only focuses on their bodies. They brought home the point that these labourers, belonging to various Dalit communities, are nothing but non-sentient tools employed by upper-caste landowners like the protagonist to increase their profits and productivity.

The caste norms are conceived and altered around the demand for this labour, evidenced by Surya’s acceptance of Laxmi’s cooking instead of the village priest’s wife, as she charged him comparatively less for it.

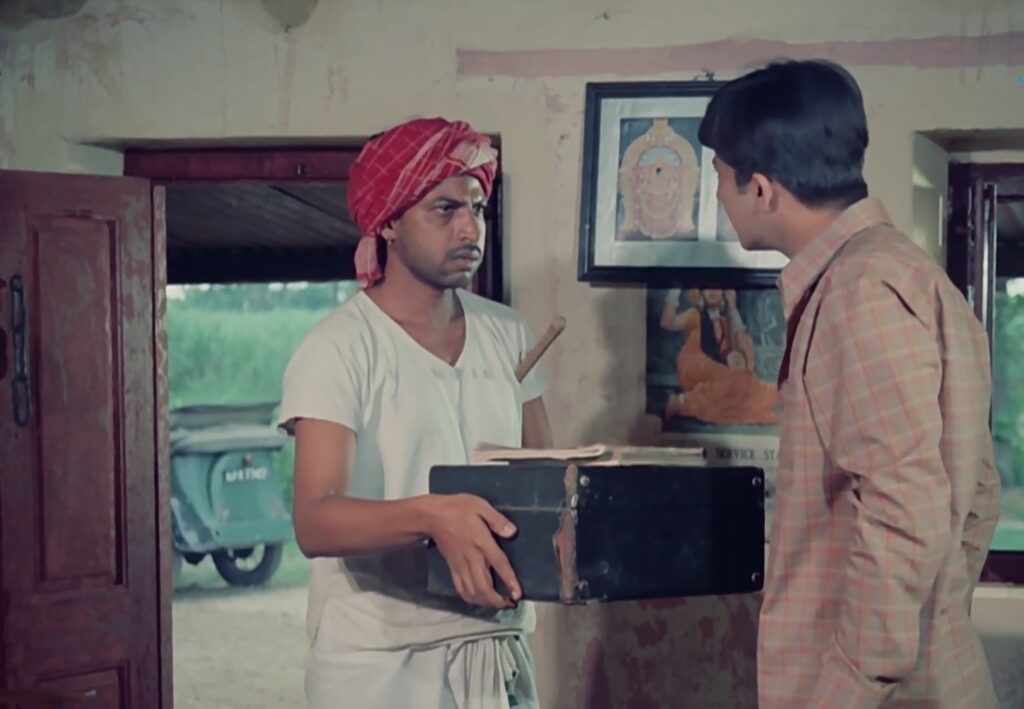

Throughout the film, Surya gets massages from the village Nai (Barber) without doing a single day’s labour. The Nai, who belongs to yet another lower-caste community by the same name, is given a contemptuous look and is asked to leave the room when the village priest comes to visit Surya, as he cannot stand to look at a Shudra in the room. It is this labour with contempt that lower caste communities in India are subjected to, where their value is directly attached to the labour they can provide, which is mostly invisible and unpaid.

The caste norms are conceived and altered around the demand for this labour, evidenced by Surya’s acceptance of Laxmi’s cooking instead of the village priest’s wife, as she charged him comparatively less for it.

The importance of Laxmi’s physical labour that defined her existence and value in Surya’s life becomes evident by the reasoning given by Surya to Saru when she insisted on relieving Laxmi of the household duties after learning of the rumours circulating about her husband and the maid. Surya argues, “if we remove her, who will clean the house, clothes, and bathrooms ?” Thus, it mirrors the upper caste logic of “tolerating impure lower castes” for their labour.

Male gaze, caste, and benevolent sexism

Dalit women in India have been called “Dalit among Dalits“. They have been threatened by sexual assault and abuse at the hands of upper-caste men owing to their easy access to Dalit women, who historically have enjoyed greater spatial mobility as working-class women in the Indian social order. This greater mobility, coupled with easy access by upper-caste men, has made their bodies a site of both desire and exploitation, a theme explored in detail by Benegal in his film.

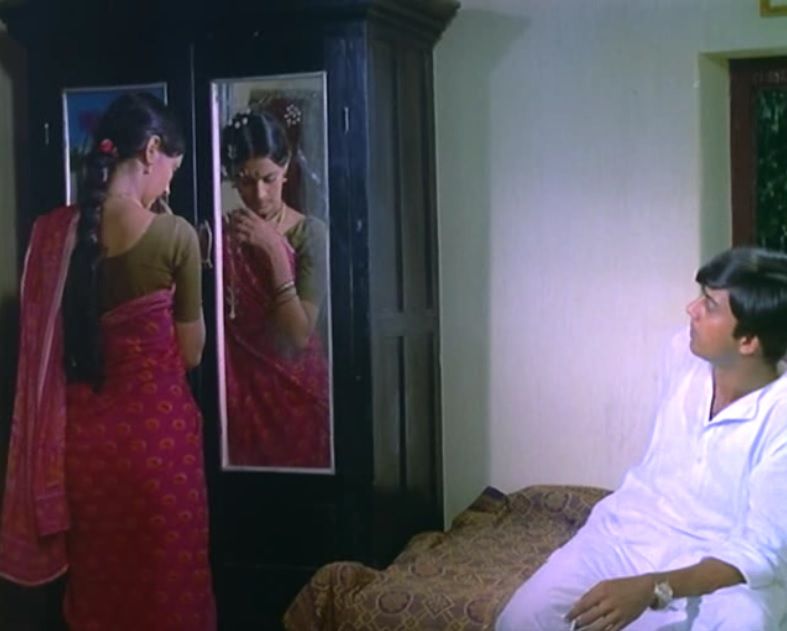

Since day one, Surya had easy and intimate access to Laxmi, who worked as his domestic caretaker. She is the first person who greets him when he comes back to his ancestral home and is the first face he sees in the morning when he wakes up. The fact that Laxmi’s husband also works for him makes it easy for Surya to isolate the two and make advances on Laxmi in her husband’s absence.

He is aware of the hierarchy between them and exploits it to seduce Laxmi; he peeps at her while she is taking a bath and walks into her hut uninvited when Laxmi refuses to show up for work after declining Surya’s sexual advances. Even Laxmi’s doorless hut is right across Surya’s mansion, making it easy for him to sneak glances at her.

Also Read: The Historical Erasure Of India’s Groundbreaking Dalit Feminism

After Laxmi agrees to consummate the relationship with him, there is a shift in Surya’s tonality and mannerisms towards her. He becomes affectionate and considerate towards her, but this transformation cannot be confused with a change of heart or virtue on Surya’s part as he continues to treat other Dalit folks in his vicinity as disposable objects. It is Laxmi who has won his benevolence by agreeing to be the object of sexual desires and is thus rewarded with this preferential gracious treatment.

A tale of two types of women

The concept of gender and caste intersectionality was not a part of mainstream cinema in India. However, with Ankur, Benegal took a deep and critical look at the gender hierarchies perpetrated by caste in India. In a very poignant and telling scene where Surya’s wife Saru visits his ancestral home, Saru is seen touching Surya’s feet to seek his blessings, a practice in keeping with Indian marriage customs. However, then Laxmi goes on to touch Saru’s feet, in keeping with the caste customs, thus solidifying the hierarchy between these two women.

We are shown two different categories of women throughout the film- those whose agency and existence are constantly denied by their caste status and those whose caste position provides them with a sense of protection and agency. For example, when an upper caste woman is put at stake and lost in a poker game by her husband to his friend, she refuses to leave her house and go with the friend.

We are shown two different categories of women throughout the film- those whose agency and existence are constantly denied by their caste status and those whose caste position provides them with a sense of protection and agency. For example, when an upper caste woman is put at stake and lost in a poker game by her husband to his friend, she refuses to leave her house and go with the friend.

Furthermore, she uses her agency to shut the door on him. The door here then becomes an important motif for the space and agency that Dalit women do not enjoy, as Laxmi literally did not have a door in her hut, thus making it possible for Surya or any other man to barge in without permission.

Voiceless existence of Dalit men

Benegal does a great job at fleshing out the complexities of Gender, Caste, and Class struggle in rural India but falls short of characterising and exploring the existence of Dalit men in these settings. The most prominent Dalit male in the film, Laxmi’s husband, is portrayed as a person with hearing and speech disability alcoholic who is intoxicated throughout the film and stays silent even when he is humiliated in front of the whole village at the behest of Surya.

Other Dalit men appearing in the film are either labouring in the field or trying to flatter Surya and fan his ego. This literal and metaphorical silencing of Dalit men and their portrayal as alcoholic, spineless, passive individuals feeds into the larger casteist narrative that invisibilises the history of active caste rebellion by Dalit men and women.

Also Read: Film Review: Ankur Portrays The Intersections Of Caste, Class And Gender

The unwelcomed seedling and the revolution

When Laxmi gets pregnant with Surya’s child, his response is to abort the child as he could not bear to associate his name with a child born out of his inter-caste union with a Dalit woman. He wants Laxmi to “go someplace else with the child.” Interestingly, this “caste-blind” educated man cannot even offer the civil treatment that his father gave to his mistress (Rajamma) and her child (Prakash) by offering them a piece of land to help themselves, thus, laying bare his casteist hypocrisy.

The film ends with a scene of Prakash, who symbolises the union of two castes standing at a crossroads between angry Laxmi and frightened Surya, signalling the uncertain future of their coming child. Its future will be filled with the same stigma and prejudice that Prakash carried all his life. Nevertheless, the ending also carries a Seedling (Ankur) of revolution as a Dalit kid throws a stone at Surya’s window, breaking it, thus signalling a breakdown of casteist feudal society at the hands of the new generation.

References:

- John, M. E. (2015). Intersectionality: Rejection or critical dialogue? Economic and Political Weekly, 72-76.

- Omvedt, G. (1979). The downtrodden among the downtrodden: An interview with a Dalit agricultural labourer. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 4(4), 763-774.