Indian Cinema has been one of the oldest and biggest film industries in the world. It has surely undertaken a long journey of producing several films, across various genres, depicting stories, characters, and society in different ways. However, has this long journey of Indian cinema and particularly Hindi cinema adequately and truly represented the Dalit-Bahujan and other marginalised communities?

It can be argued that “the hegemonic control of the social elites over each segment of the film industry has made Hindi cinema a powerful tool to promote their social interests and cultural tastes without bothering much about the representation of Dalit–Bahujan characters, their sociopolitical life, and alternative cultural values” (Wankhede, 2022).

Certain films that consisted of Dalit-Bahujan characters and their stories usually represent them in a stereotypical way as sufferers of the violent caste structure. While this accurately represents the caste-ridden society, it does not represent such characters having agency, self-respect, or a protesting-fighting-back potential. These characters are usually saved by upper-caste protagonists, displaying paternalist values and a saviour complex.

The content of cinema has largely been marked by thematic stagnation, characterised by “commercial films” based on melodrama and entertainment. These films are produced at high budgets, yet, lack a larger impact and hardly instil any changes in society.

The production and popularity of “art films” have substantially been lower if compared to their commercial counterparts. In such situations, the Dalit-Bahujan question, their political, social, economic, and cultural issues, social movements based on ideas of social justice, political overturns and many more have not found adequate representation in Indian Cinema.

Also Read: Anita Bharti: Her Poetry And Dedication To Ambedkar’s Vision

Even during the so-called Golden Age of cinema, films based on social realities did not focus largely on the caste question. Certain films that consisted of Dalit-Bahujan characters and their stories usually represent them in a stereotypical way as sufferers of the violent caste structure. While this accurately represents the caste-ridden society, it does not represent such characters having agency, self-respect, or a protesting-fighting-back potential. These characters are usually saved by upper-caste protagonists, displaying paternalist values and a saviour complex.

However, certain films in regional languages and OTT platforms have been capable of changing the narrative around the representation of marginalised communities. There are three films; Sujata (1959), Giddh (1984), and Kantara (2022) which are based on a caste-ridden society and comprised of Dalit-Bahujan characters and their stories.

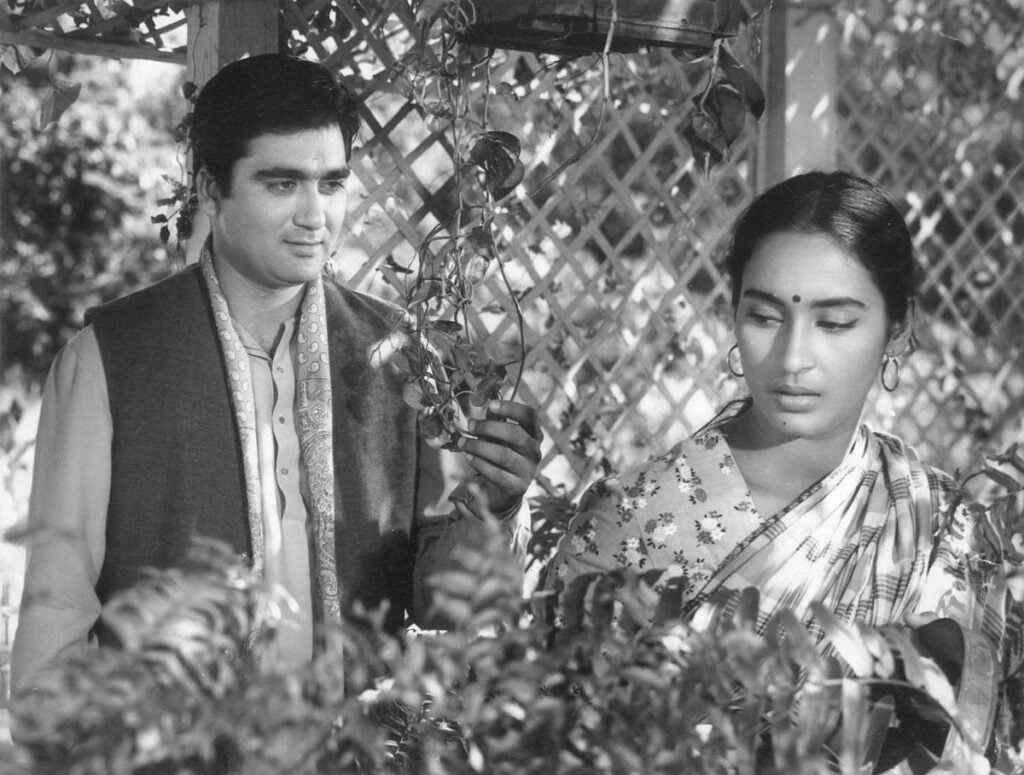

Upper-Caste paternalism and saviour complex in Sujata

Sujata is the story of an erstwhile untouchable Dalit woman who is adopted by an upper-caste, Brahmin couple in unusual circumstances. The character of Sujata is played by Nutan whose parents passed away due to cholera when she was an infant.

The film shows that she is brought to the upper-caste couple Upen and Charu by the villagers who could not find anyone from her caste to hand her over. The couple tries to send her away at different times in their lives either to her caste community or to orphanages as they fear that housing and bonding with an untouchable might bring them a bad name or some kind of heavenly injustice.

The film shows instances of untouchability being practised, like when Charu asks Bhupen to not eat from the spoon with which he has fed Sujata. However, in the long course of the film, these practices of untouchability are somewhere surpassed in the household. Sujata often gets hurt when Charu doesn’t refer to her as her daughter, the reason for which stays unknown to her for a long time. Later in the film, Sujata learns that she is an untouchable woman and her foster parents had to adopt her because they could not find anyone else who could take her responsibility. Her caste identity now makes her feel undignified and inhuman.

Soon a love interest between Sujata and the elderly relative’s grandson Adheer starts developing. Aware of her identity Sujata tries to push him away to pay back her foster parents. The film portrays that Adheer ‘educates‘ Sujata about the evil caste system and ‘helps‘ her to ‘realize‘ that she is also a human being capable of having dignity. Adheer asks her grandmother to accept Sujata by arguing that since she has lived all her life with an Upper-caste family, she is their child.

This vividly shows that the caste structure as a whole is not being transgressed or addressed. The transgression of caste is talked about in a rather paternalistic manner taking cues from Gandhian principles. Bhupen, Charu, and Adheer are shown as upper-caste reformers and saviours of a poor, destiny-stricken untouchable woman. Sujata is depicted as a meek, dependent Dalit woman with no agency who cannot survive in a world without the benevolence of the Upper-caste.

Systematic socio-sexual exploitation of Dalit women in Giddh

Giddh is a film that revolves around the Devadasi system in a feudal rural society. It shows the systematic sexual, economic, and social exploitation and oppression of Dalit women. The film revolves around the practice of converting young Dalit girls into Devdasis to please the Goddess Yallama. The protagonist of the film, Hanumakka played by Smita Patil, represents the functioning of this superstitious practice, a ploy of the feudal landlords.

According to this practice, the devadasi is supposed to serve the pleasures of the upper-caste landlord who has bought her. The lower caste population is made to accept such a practice as a religious calling, as a function of destiny. Hanumi represents that these landlords sexually exploit young girls, but once they turn older and suffer diseases they are left to die. A very powerful dialogue in the film marks that the destiny of a Dalit woman is decided even before she is born.

The feudal set-up marks that the Dalit workers are not paid according to the labour rate, but are supposed to work and cherish the lordship. The economic conditions of the household push families to either allow their daughters to become devadasis or send them to Bombay. City life is considered an aspiration for a better life.

However, as it is portrayed young girls moving to Bombay get involved in sex work and face similar precarity of life chances. A recurring theme in both these situations is that the body of a Dalit woman is considered available to the so-called upper-caste men. The film is a commentary on the devadasi system and the violence it perpetrates on the Dalit community, especially the women. It shows that once a woman is bought by a landlord, and turned into a devadasi, all her dreams and aspirations come to an end.

Hanumi marks that she wanted to get married to Basaya, but now he is her pimp. The film showcases various structures that are responsible for the systematic oppression of the Dalit community. However, the film also shows an upper-caste teacher who tries to reform the age-old system. He talks about the superstitions of the lower caste that has put them in such a situation and overlooks the deeply embedded structures. He looks like a messiah who cannot do much because of the feudal powers.

The film is an empathetic take on their lives and shows the potential that the members of the community have for fighting back and protesting in whatever meagre ways.

Dalit agency, fighting back potential, and masculinity in Kantara

Kantara is a film that received critical acclamation and rightly so from various corners. It is a wonderful take on indigeneity, their rituals, rights, and conversation with modern state apparatus in a land-conflicted area. The film actively makes several socio-political, economic, and cultural statements. The film’s larger narrative revolves around the villagers’ feudal ties with the landlord, which runs historically and spiritually.

Further, it also deals with a very important aspect of forest rights and the right over forest produce such as food and fuel by the indigenous people. It is a commentary on the conflict between modern law and indigenous culture. When the forest officer says the government has ordered the clearance of the encroachment, the protagonist, Shiva marks that they have been living here even before the formation of this modern system of governance.

Also Read: Ankur (1974) Through A Dalit Feminist Lens

The film also carefully takes upon the issue of caste-class hierarchisation and separation. The villagers are depicted as an ostracised community which cannot enter the feudal landlord’s household and eat the same food as them on the table. However, the film shows the protagonist as a man with the agency, capable of fighting any injustice inflicted upon him or the villagers.

When Shiva was refused the first prize in the Kambala race, he fights to get back his deserved medal. When a villager is hit by the landlord’s man for entering his house, Shiva retaliates but makes sure that neither he nor anyone else enters the house.

The maintenance of caste norms was depicted subtly. However, when he realises the ploy of the landlord, he not just enters his house but also sits across the dining table in defiance of such norms. After he leaves, the landlord orders that the entire house should be purified. It is interesting to note that while the landlord is following the notion of purity and pollution since the beginning, he doesn’t depict it in front of the larger public to prevent any form of outright hostility.

However, on the flip side, Kantara does not give an adequate characterisation of the women and goes on to promote toxic masculinity.

Shiva’s mother is shown as a nagging irrational woman. Shiva pursues a woman named Leela who has returned after her training as a forest ranger and is employed in the village police office. While marriage is not shown as an institution that provides legitimacy to their relationship, she is expected to perform all the stereotypical roles.

Also Read: Why Do We Need More Dalit Women & Dalit Queer Writers In India Today?

She is also punished and disregarded by the entire community when the forest officer announces the de-encroachment drive. She is physically pushed and hurt by the male protagonist. She is also shamed by the police officer for having a relationship with Shiva as the officer calls it to be a ‘service.’

In the name of love and romance, the film goes on to justify Shiva’s male gaze upon Leela. He even pinches her belly to her utter discomfort and is appreciated in his male circle. “It unapologetically centres the male protagonist, legitimizes toxic masculinity at times, reduces the female characters to their incidental selves, and walks the familiar trajectory of the ruler–ruled dichotomy“, writes Sunayan Bhattacharjee.

The character of Shiva is able to break the stereotypic display of marginalised men as passive, emasculated, and dependent on upper-caste domination. Shiva is unlike Basaya from Giddh with a skinny body, helpless and humiliated, or Kachra from Lagaan who receives validation from upper-caste men.

Also Read: Pride And Power: Dr BR Ambedkar Through A Dalit Feminist Lens

However, his masculinity and anger are romanticised at the expense of providing a meaningful characterisation to women. It makes us question the progressiveness of Dalit masculinisation. While the film is an attempt to showcase the marginalised not in a stereotypical way, it could have done much better in the themes of masculinity and female characterisation.

Films in Hindi cinema have largely been devoid of adequate societal representation. Whatever minuscule attempts have been made in this regard depict marginalised communities in the most stereotypical ways, as people oppressed without any presence of protest. However, over time the representation of Dalit-Bahujan characters and their stories have changed due to various reasons.

Also Read: How Long Should We Wait For A Dark, Dalit Malayalam Film Heroine

A new portrayal could be seen in various platforms, as rational conscious agents, social activists, and lead protagonists, who want to live a dignified life. “In the last one decade, Dalit representation has become more improvised, showcasing that they are more than just struggling, victimised bodies“-Wankhede, 2022.