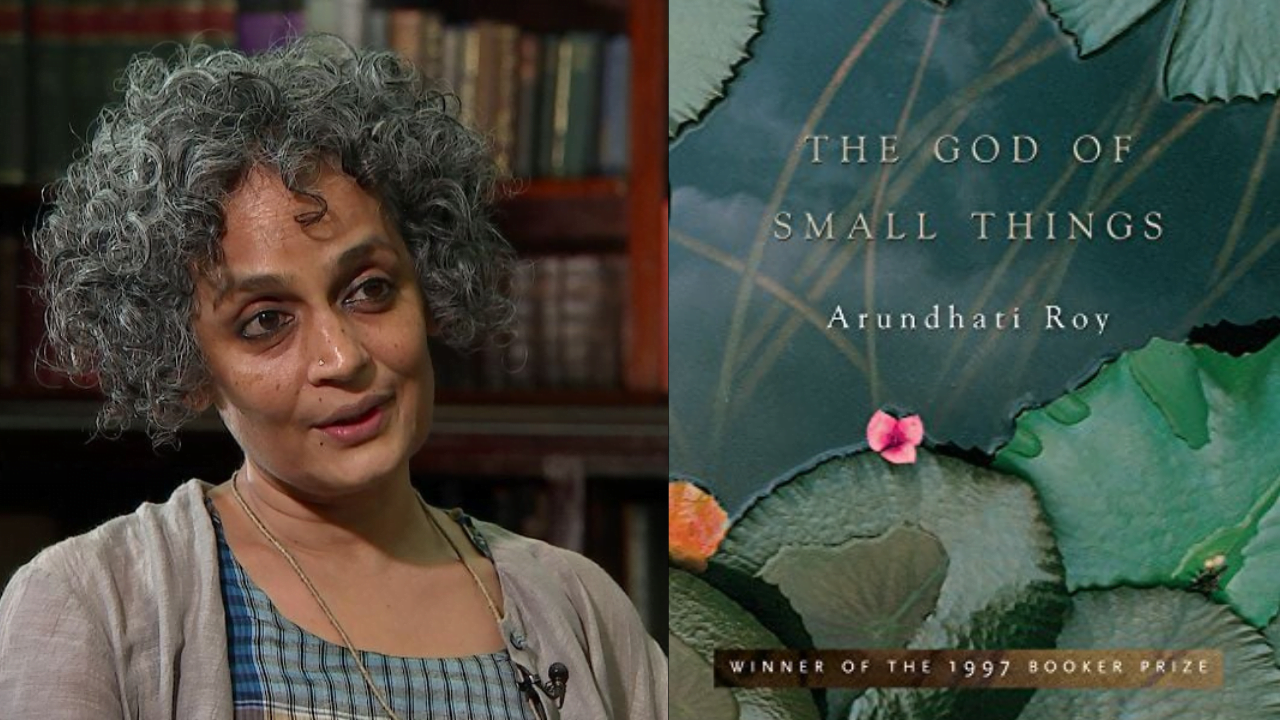

Arundhati Roy’s Booker Prize-winning book, The God of Small Things, is remarkable in encapsulating the so-called bigger issues of caste, class, politics, and gender within the smaller world of the Ayemenem family in the novel. It juxtaposes the personal with the political as it constantly plays with the idea of “big” and “small” things.

The very intimate and personal dynamics of the Ayemenem family are contextualised within the larger socio-political order. The God of Small Things represents the family as not an innocuous sphere but as mirroring many forms of hierarchies and injustices present in the larger world.

Roy’s The God of Small Things touches upon the Marxist protests in Kerala, different religious sects, environmental and cultural degradation as products of neo-colonial capitalism, and so on. However, the issues that emerge most prominently in the text are the evaluation of caste and gender politics. As a satirical comment on the “Love Laws” which define “who should be loved, and how. And how much,” the novel expounds on the relationships which are formed beyond the injunctions of these laws.

The God of Small Things is noteworthy in its mode of narration as the events are unfolded through the perspective of two young children, Rahel and Estha. These two small children, often ignored and side-lined by the other members of the family, are the central protagonists of the novel.

The most radical defiance comes through the relationship between Ammu and Velutha, as they connect despite caste, class, gender, and familial barriers. Even though their bond develops in small, discreet spaces — beyond the eyes of the public, family, and readers — it has a transgressive potential in uprooting the well-established hierarchies and social structures. This is reflected in the eventual crumbling down of the Ipe household which, throughout the novel, has posed as the microcosm of the nation itself.

Ammu, a divorced single mother of an upper-caste, upper-class family, falls for Velutha who is her social inferior in terms of class and caste dynamics, being a worker in her family’s factory business. Ammu, in the Ipe household, already occupies a marginal position being a daughter with no material possession and lacking any social standing provided by marriage. She gets more alienated from her family as she further breaks the rules of a normative family by forming a relationship with Velutha — asserting her transgressive desires and political stance simultaneously.

However, it is not only in the “bigness” of Ammu and Velutha’s violation that Roy invests her socio-political vision. The God of Small Things documents smaller incidents of interpersonal relationships which do not conform to the “Love Laws” critiqued by the text. The most apparent of these is the inter-communal marriages done by both the children of the house — Chacko and Ammu. Yet, it is the insidious, interstitial relationships which emerge in the novel which are the most interesting.

The God of Small Things is noteworthy in its mode of narration as the events are unfolded through the perspective of two young children, Rahel and Estha. These two small children, often ignored and side-lined by the other members of the family, are the central protagonists of the novel. Their innocence and ignorance of the aforementioned “Love Laws” allows them to build relationships purely on human terms.

Instead of limiting themselves to conventional familial ties — which are often dismissive and hypocritical towards them — they, too, connect with Velutha through emotional affiliation. A surrogate family comprising the twins, Ammu, Velutha, and to some extent, even Sophie Mol (their English cousin) is envisaged by Rahel and Estha. Their own relationship is unmindful of physical and emotional boundaries set for siblings as they are shown to be connected at a more transcendental level.

This critique of the caste and gender structures embedded within the Ipe household and society alike emerges most strikingly in the conclusive chapters of the novel. The small injustices, biases, and discriminations delineated in the novel culminate in a heart-rending violent crime. The whole novel with its non-linear, suggestive narration spirals towards one catastrophic event which is hinted at many points in the novel.

Ultimately, The God of Small Things attempts to depict these unconventional relationships as counters to the hypocrisies of the usual ones. The Ayemenem family becomes a symbol for various forms of caste, class, and gender oppressions: Ammu’s dispossession against Chacko’s appropriation of each material and non-material aspect of the family; the persecution of Ammu and Velutha’s relationship against the silent approbation of Chacko’s exploitation of the women in the factory; and the ousting of Rahel and Estha against the celebration of Sophie Mol as the westernised grandchild of the household.

Also Read: Gender And Neoliberalism In Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry Of Utmost Happiness

This critique of the caste and gender structures embedded within the Ipe household and society alike emerges most strikingly in the conclusive chapters of the novel. The small injustices, biases, and discriminations delineated in the novel culminate in a heart-rending violent crime.

The whole novel with its non-linear, suggestive narration spirals towards one catastrophic event which is hinted at many points in the novel. This event ultimately brings the private sphere of the Ayemenem family and the public sphere of police and politics together as united in their casteist zeal, they crush the radical opposition posited by Ammu, the twins, and most importantly, Velutha.

The budding hope and compassion felt by the readers for these non-customary relations is quashed by the narrative as the novel shows how these private and intimate bonds are incompatible with the larger socio-political reality. It is the novel’s ability to seamlessly contextualise the smaller, individual stories within the systems of capitalism, casteism, colonialism, and patriarchy that makes it both emotionally affective and politically effective reading.

The narrative style of the novel is very modernist as it employs non-linear narration, dream imageries, multiple perspectives, clever wordplays, and so on. This adds to the allure of the book as the readers are constantly kept hooked to the narrative waiting in anticipation for the central event to get disclosed. The novel opens at a time of more than two decades after the time of the primary events.

There is already an ominous feeling created as the narration talks about funerals, deaths, and separations. It is with this feeling of foreboding that the readers then enter the familial dynamics of the Ipe household.

The literary style of the novel allows it to make historical comparisons and larger socio-political comments as there is an abundant use of metaphors such as “History House,” “Heart of Darkness,” “Locusts Stand I,” etc. These metaphors form viable bridges between the personal dynamics of the Ipe household and the external socio-political reality they reflected.

Also Read: Book Review: Representation Of Charulata As A Married Woman In Nashtanir

At times, Roy also inserts the technique of Magical Realism in her text which, becoming an extension of the children’s imagination, also allows the readers to make improbable connections and get greater insights into the text’s politics.

This modernist literary style, despite providing an interesting read, can somewhat undermine the text’s political potential. First of all, it heavily borrows from Western literary styles while paradoxically critiquing colonial legacies. The text’s global appeal lies in the fact that it is able to cater to the Western gaze through its aesthetic style. Even though the novel exposes neo-colonial capitalist frameworks, it still appropriates Western modernist writing techniques.

Secondly, the book’s literariness limits its readership. It is accessible only to the educated elite due to its excessive use of literary devices in its prose. It is a valuable voice of protest for readers interested in the caste politics and gender injustices prevalent in India, but at the same time, it cannot appeal to the masses due to its complex and difficult structure. The grassroots-level politics of the work can get overshadowed by its poetic style and roundabout, indirect ways of narrating.

The God of Small Things is a novel full of simplistic details, couched in innovative prose of metaphors, similes, wordplays, episodic narration, and indirect storytelling. It is about everyday human life, a typical family, and myriad human relations — all viewed through the naïve lens of young children. However, it is in these “small” things portrayed by the novel that the larger politics of the novel are situated. It is eventually a validation of the fact that the personal and political, the “small” and “big”, cannot remain two isolated realms.