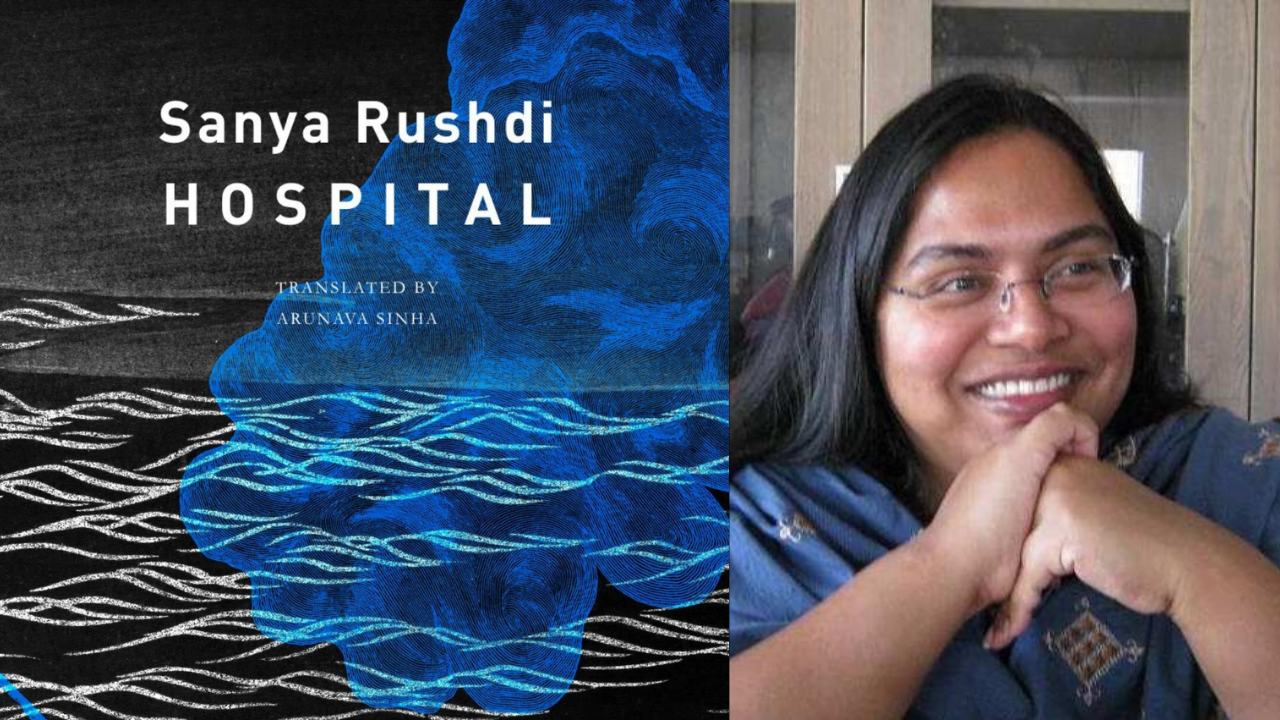

We live in an age where mental wellness is one of the founding blocks of healthy and sustainable living. Not very long ago, there was stigma and mockery attached to discussions on mental health, anxiety, and depression. In this context, Sanya Rushdi’s debut novel Hospital, translated from Bengali to English by Arunava Sinha, and published by Seagull Books, offers a critical perspective on issues related to sanity, mental trauma, society’s hackneyed and prejudiced response to mental illness, institutional apathy toward patients and survivors, and the struggles and conflicts within familial relationships upon the realisation or discovery of a loved one’s mental condition.

Curing psychosis through prescription

The protagonist, who shares her name with the author, is in her late thirties and undergoing medical treatment for psychosis. As straightforward as it may sound, Sanya’s journey follows a spiral path where the twists and turns open up new problems the solutions to which cannot be obtained through a conventional or prescribed route. On the verge of her third episode of psychosis, Sanya begins to question the institution of medical sciences which, according to her, lacks novelty in its treatment methods and is in desperate need to alter its ways of engaging with patients.

Also Read: The God Of Small Things: The “Big” And “Small” Things In It

As a student of developmental psychology herself, who could not complete her PhD in the subject because of her own mental health issues, Sanya’s character lends a credible voice to the community battling mental illness, societal discrimination and judgement. With utmost sensitivity and precision, Sanya exposes the loopholes in a standard, positivist diagnosis of a mental condition, which is not only limiting but futile as well.

Source: Bohiprokash Books

During a conversation with the doctor at the Monash Medical Centre, Melbourne, Australia, Sanya urges the medical fraternity to go beyond the script and apply the tools of conversation and language as healing techniques to understand the mindscape of a patient. She argues how debilitating the effects of medicines and injections could be on a person’s overall health and mental stability. The immediate response to ‘calming’ a mental patient is a flawed notion and needs introspection. The perception that the doctor knows what is ‘best’ for the patient creates a hierarchical equation where the doctor commands and the patient ought to obey. This is a form of coercion which leads to a severe blow to a patient’s self-esteem and dignity.

Healing: Employing care or coercion?

In one of the telling incidents, when Sanya refuses to use a wheelchair and expresses her desire to walk instead, the medical authorities and police officers warn her that if she doesn’t comply, she will be ‘made to’. Now, this imposition of a ‘rule’ on someone who is assumed to be psychologically ‘unstable’ and is therefore in need of assistance is in fact a deliberate homogenising of the experiences of mental health patients across diverse social backgrounds and contexts.

Sanya, who has experienced the worlds of both a community house and a medical centre, draws a comparison between the different kinds of ‘cages.’ The community house is perhaps more liberal and relaxed about rules than a hospital where permissions and applications are mandatory. In a community house, Sanya could go out and visit a library and come back, eat what she liked, and so on; in a hospital however, she cannot under any circumstance venture out without assistance or a nurse in tow. She is under constant surveillance and her mobility is restricted.

Experiences cannot be universal. The officials in-charge and the medical staff on duty are somewhere incapable of deciphering the specific needs of the residents. The institution is designed in a way that somewhat mimics an architecture of confinement (not healing or care) where you are constantly monitored and your actions are controlled.

Finding freedom in imprisonment

Sanya, who has experienced the worlds of both a community house and a medical centre, draws a comparison between the different kinds of ‘cages.’ The community house is perhaps more liberal and relaxed about rules than a hospital where permissions and applications are mandatory. In a community house, Sanya could go out and visit a library and come back, eat what she liked, and so on; in a hospital however, she cannot under any circumstance venture out without assistance or a nurse in tow. She is under constant surveillance and her mobility is restricted.

Source: Ashoka University

The community house, Sanya feels, “allows something like the ‘self’ to exist, something like ‘me’, something like ‘want’…On the other hand, no such thing as ‘self’ is allowed to thrive in hospital…The self is subdued with medication…” In a hospital, Sanya’s autonomy is compromised. She has no agency or choice. At every instance, Sanya is reminded to ‘calm down’ and given mood stabilisers and injections at the slightest pretext which she protests vehemently against each time.

People who need security and care do not deserve to be oppressed by society, which labels them ‘insane’ and ‘abnormal’ and pushes them into confining, suffocating boxes where their self, individuality, and creativity are repeatedly crushed in the guise of being cured of their illness. This is a gross violation, points out Sanya, and makes it clear by questioning, “Is this medication-based, ‘collaborative’ and ‘collectivist’ system really doing anything ‘individualized’ for such people?”

Ethics of care and feminism

Within the paradigm of feminist ethics of care, it is essential to challenge and demystify the ‘normative’ and ‘andro-centric’ conception of care and well-being. As argued by Janet Johansson and Michaela Edwards, “an ethic of care does not promote dependence on others due to power structures, but it emphasizes freedom of choice and action.” According to Liedtka, 1996; as cited in Johansson and Edwards, 2021, “to care for others is not to impose solutions for problem-solving purposes, ‘to care means to respect the other’s autonomy and to work to enhance the cared-for’s ability to make their own choices well.’”

Also Read: Funny Boy: A Search Exploring Identity, Sexuality And Politics

Therefore, the idea is for both the doctor and the patient to meet at a level-playing field where the patient is free to voice their concerns and opinions and is not silenced or reduced to being a victim of gaslighting. As Sanya explains to Dr. Nevin during one of the ‘scheduled interviews’, to track a patient’s ‘progress’, “The mind is not the body, it’s not an object. Mental issues, mental problems are not sensations that can be fixed with things, with objects, with medicine.” Also, ‘confinement’ cannot be the ‘cure’, it only perpetuates ‘coercion’.

Source: Giramondo

Another striking aspect in this novella is that the caregiving staff comprise mostly women and those occupying the highest seats in the medical establishment are invariably men, the decision-makers on the fate and destiny of either an incoming or outgoing patient. So, the one who ‘dictates’ is a male doctor or a male counsellor. And those who serve and take care of hospitality, cooking, etc., are women.

Hospital and the yellow wallpaper

While reading Hospital, one can draw parallels with Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story The Yellow Wallpaper, which was first published in New England Magazine (1892). The thematic concerns in terms of the development of a woman’s conscience and consciousness in an enclosed space between these two stories that are 130 years apart are unmistakably intertwined. In today’s parlance, the character of the husband in Gilman’s story can be called as someone who is gaslighting his wife by virtue of being a medical expert/practitioner. Relegated to the top-floor room (nursery) of a rented country house, the narrator feels claustrophobic and locked up.

Like Sanya’s character, the woman in Gilman’s story has a secret diary where she pours her heart out. The husband goes to the extent of forbidding even the act of writing for her ‘own good’. Such is the patriarchal hold over a woman’s autonomy that she is denied even a glimmer of respite, recreation or self-expression. Her lived-experience embodied reality, and her sufferings are dismissed as signs of ‘madness’ which need immediate ‘cure’.

Like Sanya’s character, the woman in Gilman’s story has a secret diary where she pours her heart out. The husband goes to the extent of forbidding even the act of writing for her ‘own good’. Such is the patriarchal hold over a woman’s autonomy that she is denied even a glimmer of respite, recreation or self-expression. Her lived-experience embodied reality, and her sufferings are dismissed as signs of ‘madness’ which need immediate ‘cure’.

Though the earlier readers regarded Gilman’s story as a gothic/horror tale, it was much later that the text was interpreted as a strong treatise against patriarchy and the institutional provisions by way of rehabilitation centres that had a “punishing regime for depressed middle-class female patients (that) involved strict bed rest with no reading, writing, painting and, if it could be managed, thinking.” In the case of Sanya too, the medical staff complains that she “thinks a lot”. The question is, why is a ‘thinking’ woman and her cognitive prowess considered problematic or threatening even? In this case, a woman, who is mentally ill and possesses the power of rationality and articulation, is in fact, ‘doubly’ suppressed because of her gender and mental illness. None of the male inmates at the Monash Medical Centre are considered to be ‘thinking too much’ nor are they questioned about their cognitive ability or the lack of it.

Going against the tide of patriarchal dogma and institutional coercion, both Sanya and Gilman’s narrator document their experiences for posterity. They use the power of language and comprehension. Sanya is a psychology student and can convincingly argue why lithium cannot be an answer to mental illness; on the contrary, it can be severely damaging to both a patient’s mind and body.

Going against the tide of patriarchal dogma and institutional coercion, both Sanya and Gilman’s narrator document their experiences for posterity. They use the power of language and comprehension. Sanya is a psychology student and can convincingly argue why lithium cannot be an answer to mental illness; on the contrary, it can be severely damaging to both a patient’s mind and body. Conversation over didactic therapy or medication is the only pragmatic solution that medical experts, therapists, and counsellors should employ while being sensitive to those going through mental issues, pleads Sanya.

Home is where the hospital is

One of the poignant scenes in the story is when Sanya’s mother comes to visit her in the hospital carrying a bouquet of flowers. Sanya replies, camouflaging immense hurt, pain, and betrayal, “There’s no room here for flowers, you’d better take them home. They’ll look better there, they’ll thrive too.” This is the crux of it all. Flowers will bloom in a place where there is an abundance of sunshine, air and water – where there is a hint of life. A hospital is antithetical to that. Here, darkness, pungent smells of strong medicines, and emptiness, all convey a sense of morbidity.

Despite all gloom and despair, there are uplifting moments too. Sanya discovers the joy of unconditional friendship and love within the quarters of the Monash Medical Centre. She keeps going back to one particular image – one of the hospital walls painted with “blue and orange waves, like the reflection of the setting sun in the water.” This scene on the wall is a description of life, of movement, of rhythm and that is positive. The book cover, beautifully designed by Sunandini Banerjee, perhaps takes inspiration from this very image of the floating hues of blue and orange.

Also Read: “Bacha Posh” An Oppressive Tradition In “The Pearl That Broke Its Shell”

Sanya Rushdi’s Hospital is not just an act of magnificent storytelling, it is a vehement plea to be heard, to be recognised, respected, cared for, and loved. It is a story of empathy, compassion, and warmth.

The novel, Hospital, published by Seagull Books, is available on Amazon.

About the author(s)

With over 10 years’ experience in publishing and journalism, Ipshita Mitra has a Bachelor’s degree in English Literature from Miranda House, DU and holds a PG Diploma in English Journalism from IIMC. She did her MA in Gender and Development Studies and is currently pursuing her PhD in Gender Studies from IGNOU.

She has worked with The Times of India, The Asian Age, The Quint, Om Books International, World Monuments Fund India Association, and The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI). In 2016, her short story ‘Cacophony of Silence’ was published by Nikkei Voice, a Canadian-Japanese newspaper. In 2020, her short story ‘Bohemian Sailor of the Gulf’ was published by Sublunary Editions, a Seattle-based independent publisher. The Indian Quarterly (April–June 2021) published her short fiction, ‘Kabuliwala Returns’. She writes on books, culture, environment, and gender for TerraGreen, The Hindu, Scroll.in, The Wire, Wasafiri, Firstpost, Huffington Post, India Currents, and others. She tweets @ipshita77.