In the Apple TV dramatisation of WeWork’s rise and fall, WeCrashed, Anne Hathway’s Rebekah Neuman wonders, “Why do they hate us so much? We just wanted to make the world a better place.” The series emphasises how the Neumans insisted on their desire to elevate the world’s consciousness, touch its soul, and make a difference they can never truly articulate, even as the company’s finances and culture reeked of mishaps and exploitation. I often think of this when I see social media and tech companies like Twitter, Facebook (now Meta), Google, Apple, etc. harp about real change starting through conversations, connecting the world as a community, not being evil, and thinking differently.

“Twitter is a private company now so they can easily say they’re not answerable to the general public. Its entire existence has been about benefiting from the people using the platform. It is now asking people to pay for a premium experience, too. Cinemas don’t take responsibility for the content that makes it to theatres but they are responsible for your safety inside the hall in case of fire or any other crisis. So platforms benefitting from people’s existence on their digital networks cannot wriggle out of their responsibility to ensure a fire equivalent incident doesn’t occur and if it does, then it takes necessary measures to keep the people safe.”

Shephali Bhatt

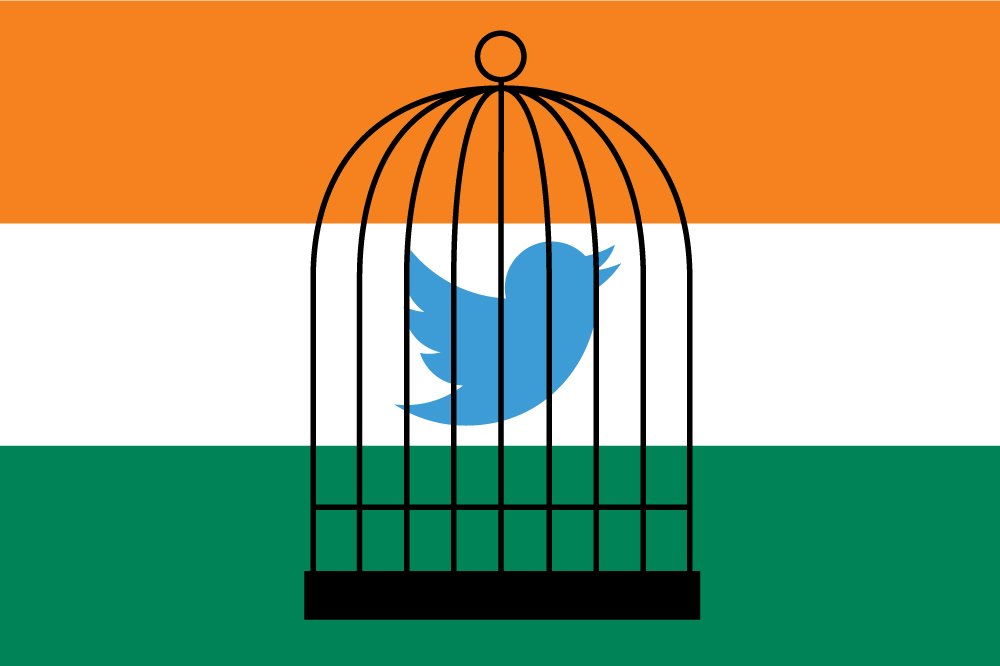

After all, they are companies — and what kind of business sense lies in fighting for “real change” when you can be asked to pack your bags and leave your place of business? Twitter’s recent Transparency Report from the first half of 2022 revealed that it had to comply with legal requests for a content takedown from these four countries more than the rest: Japan, South Korea, Turkey, and India. Combined with India’s political and cultural climate on free speech, with India slipping to 161 out of 180 countries in the press freedom ranking, Twitter’s compliance and the report should make it evident if it weren’t already so, that between the suspicious desires of ‘real change’ and very real governmental censorship, it’s the dissenting public which pays the price.

Trends and transparency on twitter

In India, accounts and posts by journalists, socio-political commentators, civil rights groups, and political leaders have been blocked and removed for various reasons from 2021 through 2022 during COVID-19, protest movements against the contentious CAA, for farmers’ rights, and other moments of political unrest in various Indian states. While the Right to Freedom of Speech is not absolute and is legally expected to have reasonable restrictions, explains Radhika Gupta — law apprentice and tech enthusiast, when the ambit of these restrictions is broad and vague, it can be misused in silencing people to suit the administration’s interests.

The Lumen database, used to document and analyse complaints and legal requests for the takedown of online material, showed that even for the period not covered by the Transparency Report, nearly 122 Twitter accounts were blocked within a week. So, it’s not surprising seeing these trends that India was a major contributor to the 53,000 legal requests for content takedown as well as to the 16,000 user data requests from Twitter in the first half of 2022.

“The report for H1 2022 is significantly less informative than previous versions – which were already critiqued for not conveying information granularly enough. Combined with Twitter (intentionally or unintentionally) no longer making disclosures to the Lumen Database, this is equivalent to moving several steps backwards when it comes to transparency from social media platforms.”

Prateek Waghre

But now with the access to these trends and data becoming even more limited, our complicated relationship with social media platforms is on further shaky ground. Prateek Waghre, Policy Director at the Internet Freedom Foundation, is concerned as he explains: “The report for H1 2022 is significantly less informative than previous versions – which were already critiqued for not conveying information granularly enough. Combined with Twitter (intentionally or unintentionally) no longer making disclosures to the Lumen Database, this is equivalent to moving several steps backwards when it comes to transparency from social media platforms.”

According to the previous Transparency Report that Waghre mentions, India had made a total of 3992 removal requests, withheld 88 accounts, and demanded information a total of 2211 times for user data and content in the second half of 2021. This time, while the specifics remain unclear, Waghre thinks the fact that takedown requests in the first half of 2022 were 5 times higher than in the second half of 2021 is poignant and “confirms the growing trend of states looking to actively police speech on the internet through legal requests.” He sees this as worrisome since “[w]hile one would expect the numbers to rise as more people communicate over social media platforms and law enforcement agencies ramp up their monitoring efforts, a 5X growth is significant and concerning.”

No serious billionaires for free speech on social media

Elon Musk, who purchased Twitter on October 27 in 2022, claimed to be a free speech absolutist while making the deal and even restored several controversial accounts banned for various reasons, including the spread of misinformation. Almost simultaneously, he was reported to be banning and shadow-banning Twitter accounts that criticized Musk or posted dissenting tweets. This turncoat persona was on display once again when Musk told BBC on Twitter Spaces that “[t]he rules in India for what can appear on social media are quite strict, and we can’t go beyond the laws of a country… if we have a choice of either our people [to] go to prison, or we comply with the laws, we’ll comply with the laws.” From one billionaire to another, Logan Roy from Succession echoes a lot of what we feel about these actions (sans the love).

But on a serious note, Musk’s attitude is reflective of the plainly opportunistic motto for social media platforms. While much has been said about their ability to provoke social and political change, form communities, and offer a platform to people, their interests and growth-oriented algorithms do not have to be in congruence with democratic goals.

Also Read: #CasteistTwitter: Minorities In The Time Of Social Media

Radhika Gupta calls this the “business side of things” and explains that social media platforms, which are regarded as intermediaries under Indian law like the IT Act and the IT Rules, are between a rock and a hard place too because they cannot do business without following the law of the land as these laws are “pretty strict”. She elaborates that India has a big youth population, and we bring in about 300 million users on the internet; these companies have to take care of businesses which will suffer without government approval. This can be seen in TikTok’s case, banned in India in June 2020, within the blink of an eye due to geopolitical tensions with China.

However, Shephali Bhatt, an Internet culture reporter from India, argues that there is a strong onus on these platforms in pushing back against human rights crises like censorship and the spread of hate speech, even if “Twitter is a private company now so they can easily say they’re not answerable to the general public.”

The creator economy that relies on the presumption on social media platforms is made of over 50 million such people, but the influx of money in such an economy is unevenly on the side of platforms that boost their revenues while less than 0.1% of creators can make a living from it. And these reports are proof that none of these creators, as well as several millions of journalists, political commentators, and activists, can rely on these platforms for the bare minimum accountability, let alone protection in case of political pressure.

When asked why this social responsibility and accountability matter, Bhatt explains to FII that the hypocrisy at play here, “[I]ts entire existence has been about benefiting from the people using the platform. It is now asking people to pay for a premium experience, too. Cinemas don’t take responsibility for the content that makes it to theatres but they are responsible for your safety inside the hall in case of fire or any other crisis. So platforms benefitting from people’s existence on their digital networks cannot wriggle out of their responsibility to ensure a fire equivalent incident doesn’t occur and if it does, then it takes necessary measures to keep the people safe.”

Also Read: The Cultural Significance Of Desi Twitter In Fostering Freedom Of Expression

The creator economy that relies on the presumption on social media platforms is made of over 50 million such people, but the influx of money in such an economy is unevenly on the side of platforms that boost their revenues while less than 0.1% of creators can make a living from it. And these reports are proof that none of these creators, as well as several millions of journalists, political commentators, and activists, can rely on these platforms for the bare minimum accountability, let alone protection in case of political pressure.

To this end, Prateek Waghre makes the case for a compelling middle-ground that might make these platforms pay attention to democratic values for their commercial gains. He argues, “Aiding democratic transparency should be a key goal for social media platforms. Even if they don’t believe that for various reasons, given the state and temperature of regulatory discourse around the world, it is in their selfish interests to do so.”

His logic is rooted in the sociological concept of institutional isomorphism that technology and social media researcher at Microsoft, danah boyd, explains as follows: “[T]here are structural reasons why companies in entire sectors tend to do the same darn thing.” boyd recently related this tendency of corporations and institutions to mimic, coordinate, and pressurise each other into normativity, to the layoffs in the tech industry and Waghre argues that within the rise of governmental regulations on social media platforms across the globe, it is in their commercial interest to look long term as “[w]e should be concerned that similar dynamics [of institutional isomorphism] could play out here as well”.

The tools for speaking truth to power

While the extent of the rise in the legal requests for content takedown from India remains unclear and the report does not specify how many of these pertain to political commentary, India’s contentious amendments to IT Rules 2021 reflect the extent to which governmental regulations on social media platforms and free speech are being normalised. Regulations like these can add to the concerns that Bhatt has, who considers herself a journalist first and then a creator, as she shares that “the current climate on the internet and especially on Twitter is a reminder of how much harder it’s getting every day to speak truth to power. It’s not just censorship but also the inaction on hate speech and misinformation that leads to violence.” She is disturbed by the indifference of the platform to matters of transparency, revealing, “Twitter’s press email [ID] automatically sends a poop emoji in response to your media queries.”

Also Read: On Elon Musk’s Twitter: Chaos, Dissent And Social (Media) Justice

So, while promises of tech billionaires and social media platforms to elevate the world’s soul and its consciousness are preposterous when seen in the light of day, Bhatt points out the awareness journalists, activists, and political commentators might want to remind themselves of time and again — social media is one tool of many in organizing for social change and impact. “It’s hard to take this platform seriously anymore even as it remains one of the more crucial platforms to share and discover news from around the world and fight misinformation,” she laments, and then adds, “So you remind yourself it’s a platform at the end of the day and if it’s not serving its purpose then you find alternatives. The key is to find ways to make sure the truth travels far and wide.”