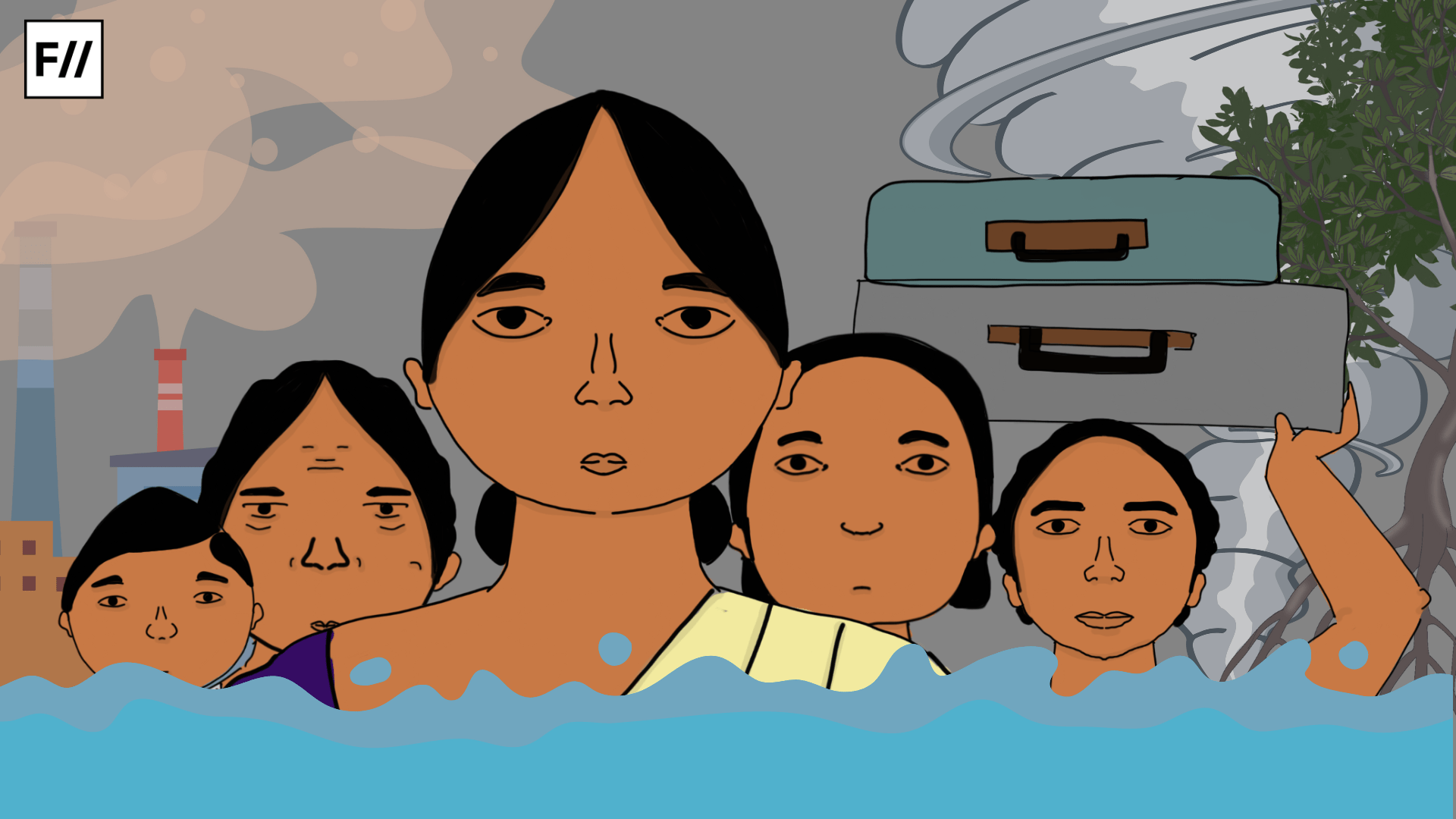

Mass migration, either acute or over a period of time, is often consequential to a crisis. Naturally, with the onset of the climate crisis, we must reconsider our understanding of mass migration as just as affected by factors of weather and ecology, as by economics, persecution or conflict. Climate migration is usually affected by several factors compounding into this final decision to shift away, with persecution, conflict, and economics often intersecting with ecological changes.

In order to map climate migration, rather than separating factors, it would be more valuable to understand certain regions of experiences where these factors intersect.

Vanishing land: Sea level rise

People move because of “natural” disasters, especially along flood and cyclone-prone coasts and islands. Fossil fuel exploitation by booming industries has heated the globe to the point of glacier melting—which mostly affects communities living in the middle of or nearby the ocean. Ministers of Pacific island nations have endorsed the fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty because these nations are rapidly sinking.

The world already witnessed the disaster-fuelled refugee and humanitarian crisis during the Pakistan Floods last year. The entire population was forced to move in mere weeks due to an acute disaster. These countries and their people have the least responsibility for causing the climate crisis and are yet subject to the loss and distress that comes.

Now, understanding the gradual changes as land goes underwater is a matter of understanding. At this rate, largely populous parts of megacities such as Mumbai and Kolkata are predicted to go underwater, over time. In coming years, we may see major changes in the migratory trends, economics and populations of these locations.

Coastal challenges: Ports, destroyed coastlines, and “development”

Ever since the colonial construction of ports across the coasts of India, indigenous coastal communities have been displaced and robbed of their right to their cultural livelihood. Right now, post-independence, government bodies and corporations are still reliant on these notions of “growth” and “development”.

The Konkan coast, Nicobar Island, and West Bengal are now subject to a multitude of projects that are, often, in direct conflict with the interests of inhabitants and environmentalists. Many have already been forced to shift their communities further in-land, where they can’t practise the same lifestyle of traditional fishing. The projects risk environmental degradation in favour of economic growth, which results in a subsequent loss of biodiversity and livelihood. This impacts their socio-economic access as a community.

Deforestation for development also increases the risk of flooding due to the destruction of mangroves—a keystone species that not only serves an integral role in coastal ecosystems and fishing community’s livelihoods but also protects coastlines from damage during cyclones, floods and storms. Its destruction simply paves the way for more loss of homes.

Deforestation for development also increases the risk of flooding due to the destruction of mangroves—a keystone species that not only serves an integral role in coastal ecosystems and fishing community’s livelihoods but also protects coastlines from damage during cyclones, floods and storms. Its destruction simply paves the way for more loss of homes.

India’s Blue Economy is an ambitious project that poses several challenges for fishing communities, who have been historically living in harmony with the ocean. Still, developmental projects echo the same colonial, casteist, and (often) unlawful private and public seizing of land. Until a more intersectional approach to sustainable development is put into place, people will still be forced to leave behind their houses, heritage, and histories.

Notes on the forest “conservation” bill

During the international Biodiversity COP15 last November, the first draft publication prepared by policymakers failed to recognise the integral importance of indigenous peoples to the ecosystems they inhabit. Fortunately, later drafts did include more negotiations and statements by indigenous peoples.

“Fortress Conservation” is the concept where indigenous people are labelled “encroachers” and subsequently forced to leave the natural body. What this approach fails to recognise is that indigenous people, who comprise less than 5% of the global population, protect 80% of the entire world’s biodiversity—which goes to show that their cultures of stewardship are critical for ecological and community wellbeing.

Still, the concerns that emerged were specific to the risk of human rights violations in the name of conservation.

“Fortress Conservation” is the concept where indigenous people are labelled “encroachers” and subsequently forced to leave the natural body. What this approach fails to recognise is that indigenous people, who comprise less than 5% of the global population, protect 80% of the entire world’s biodiversity—which goes to show that their cultures of stewardship are critical for ecological and community wellbeing.

The recent amendments to the Forest Conservation Act may simply facilitate the exploitation of critical land by public and private actors, for fossil fuel extraction and mining.

As seen in forests and, especially, in national parks across the nation, indigenous peoples are evicted under colonial norms of conservation. When they are forced to leave behind their ways of living and migrate to other locations, they are further persecuted and are, thus, constantly displaced.

Climate-affected migrant labour: Forced migration

Many farming, fishing and indigenous communities have had to change their livelihoods to adapt to rapidly changing climatic conditions and oppression. The Climate Brides podcast has also documented how the climate crisis is exacerbating child marriage and subsequent migration, as families are unable to provide for their children and marriage enables girls to be employed for their labour in industrialised disaster-prone areas. Often these large-scale agricultural industries (like the sugarcane industry) participate in monocropping that worsens environmental conditions and are owned by landowners from dominant castes who persecute migrant workers.

With rising food insecurity, rural underemployment and poverty, people are also increasingly navigating rural-to-urban migration—particularly in middle-income countries such as India. In cityscapes, they face further vulnerability to heatwaves and floods, wherein their working and living conditions tend to be in low-shade and low-elevation areas. Those with disabilities face additional challenges in accessing basic accommodations while migrating.

Urban poverty’s restricted access to basic facilities like water supply, healthy & adequate food, healthcare, education, safe & dignified working conditions and housing perpetuates the same cycle of insecurity.

Pollution-prompted migration

Although not as large-scale, there is also an existence of migration between highly polluted areas with lesser pollution.

Highly polluted areas tend to be hazardous and especially so for people with chronic illnesses, likewise when it comes to heatwaves and heat sensitivity. For some, migration may be about the necessity of navigating the health impacts of the climate crisis. Evidence suggests that a significant rise in air pollution levels in a particular location may result in emigration.

Highly polluted areas tend to be hazardous and especially so for people with chronic illnesses, likewise when it comes to heatwaves and heat sensitivity. For some, migration may be about the necessity of navigating the health impacts of the climate crisis. Evidence suggests that a significant rise in air pollution levels in a particular location may result in emigration. This is generally only possible for those with enough socio-economic privilege to do so and those stuck in bonded labour are unable to migrate for better health and living opportunities.

Migration by choice

Interestingly, lifestyle migration may also be linked to the climate crisis—where people who have the financial means seek to live “better lives” and move to less urbanised locations with better-conserved nature. It is well-known that spending time in nature is good for one’s psychological well-being and many choose to migrate for this prospect or with this as an influential factor in their choice.

While this may sound like a justified quest for satisfaction, a better lifestyle and improved health, it is imperative to note the intentions. The loose definition of lifestyle migration can also encompass super-rich preppers building bunkers or space projects to escape the havoc they fuelled. Naturally, this cannot be considered “migration”.

But in the case of lifestyle migration, in general, if so many people with the privilege to choose are leaving the city’s pollution—which they are at least slightly responsible for—it implies that so many of these places have no hope for restoration. If this becomes a trend in the years to come, powerful people and industries will render lands inhospitable, pushing the workforce from one powerhouse megacity to another—a dystopian concept for sure, but with seeds of truth today.

And the disaster-caused climate refugee crisis

If we are to discuss climate-fueled migration, it is even more critical to understand the implications of acute disasters and gradual movements. In the events of the previously discussed floods & cyclones, prolonged droughts, mass fires or other climate disasters, inhabitants of a home become refugees.

Several regions, especially in the global south, have been slowly rendered infertile and inhospitable due to industries, generally set up by the global north or by oppressive entities. Some regions changed in a span of a few hours or weeks, leading to a sudden loss for its inhabitants. Some regions are facing gradual weather changes and loss of nature, signalling the worse to come.

Several regions, especially in the global south, have been slowly rendered infertile and inhospitable due to industries, generally set up by the global north or by oppressive entities. Some regions changed in a span of a few hours or weeks, leading to a sudden loss for its inhabitants. Some regions are facing gradual weather changes and loss of nature, signalling the worse to come.

Those most affected by the climate crisis are the ones who are most displaced and the ones who face additional challenges in migrating. Persons with disabilities, people of marginalised genders, and people of marginalised castes face complex discrimination when migrating—yet, their specific mobility concerns, safety needs, and positionalities are structurally excluded from climate adaptation and environmental policy-making.

If we are to advance mitigation and adaptation strategies, we must recognise a growing global and local migration of people. Adaptation must include climate refugees and climate migrants, ensuring local, national and geopolitics do not hinder the rights, needs and accommodations of the millions of people displaced by a crisis only some of us are responsible for.