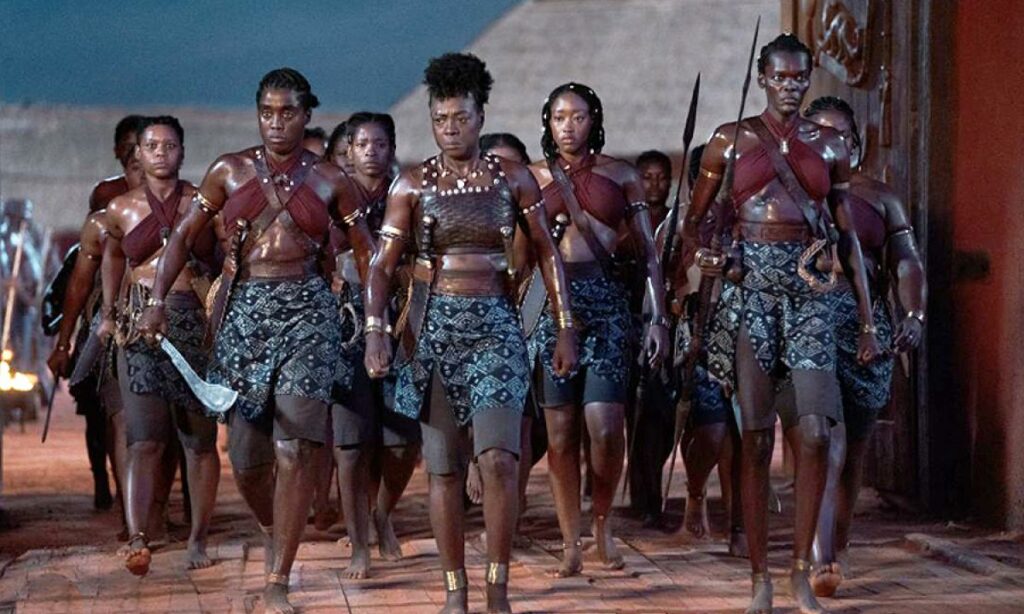

EGOT Viola Davis returns to screen fiercer than ever as an army general, Nanisca, in Gina Prince- Bythewood’s latest directorial effort, The Woman King (2022). However, she is not just an army general but the leader of the ‘Agojie,’ often referred to as the ‘Dahomey Amazons,’ an all-women army that protects the West- African kingdom of Dahomey.

As Davis alongside her co-stars, Thuso Mbedu (Nawi), Lashana Lynch (Izogie) and Sheila Atim (Amenza) delivered outstanding performances with ferocious and vigorous fighting, the production team (Davis included) struggled to fight off-screen, while pitching the historical epic that was centred around strong, women of colour.

The main question eating away at audiences after watching this empowering film seems to be, is the Agojie real? And the answer is yes. Very much so. Although the characters of the Agojie in the film are fictionalised, the story is based on the warriors who protected the Kingdom of Dahomey dating back to the 17th century. Initially, King Huegbadja (reigned circa 1645-85) created a corps of women elephant hunters. An alternative theory states Queen Hangbe introduced women warriors as a part of her palace guard in the early 18th century.

Eventually, the Agojie under the leadership of King Ghezo (as portrayed in the film) ushered in the golden age of Dahomey in their peak form. The male population had dropped significantly due to ongoing battles and this created an opportunity for women to replace the men on the field.

While the concept of gender equality seems modern and new age, the true history lies within colonised nations, places like Dahomey, Benin and many more. These nations embraced the culture of gender equality, treasuring their strong and powerful women while the colonisers were the ones to eradicate their original systems.

With the onset of French colonisation, the Agojie fought bravely for their people but were slowly wiped out. The French deemed their practices barbaric and uncivilised, and did everything in their power to wipe out the history of these female warriors. While the concept of gender equality seems modern and new age, the true history lies within colonised nations, places like Dahomey, Benin and many more. These nations embraced the culture of gender equality, treasuring their strong women while the colonisers were the ones to eradicate their original systems.

In Dahomey, the French colonisation dismantled any status that women had, preventing them from not only their original positions as warriors but also from serving as royal cabinet ministers and educational opportunities.

The popular narrative in history is that the colonisers gracefully inducted ‘barbaric‘ societies such as these, into civilisation. Yet, did anyone pause to question, how civilised were the European nations, with their oppressive, racist and unequal ideals in the first place? It is time that we flip this narrative, and begin telling the true stories of the societies pre-colonisation, the cultures and values which they had, which were already miles ahead.

Marvel’s Black Panther shattered records with its box office success, starring a prominent all-women guard, the ‘Dora Milaje‘ meaning ‘adored ones.’ These powerful warriors, protecting the King and the nation of Wakanda, were based on the forgotten legends of the ‘Agojie.’ As was seen in Black Panther and now in The Woman King, the idea of men and women leading and protecting their nation was brought forward.

This idea was not just put to the screen for a cinematic appeal or a ‘woke’ agenda, but as many African historians have stated, was often the political structure of pre-colonial Africa. Without eurocentric ideals, cultural genocide and the preference for white aesthetics, African society held their own beliefs close, ones which are seemingly more inclusive, equal and one might even say modern.

Time writes: Henrik Clarke explained in his essay on African Warrior Queens in Black Women of Antiquity, in the years before colonialism, “Africans had produced a way of life where men were secure enough to let women advance as far as their talents would take them.”

The vibrancy of the colour and patterns throughout the film adds to the intensity of the women of the Agojie. Costume designer Gersha Phillips evidently put great effort into her research and drew inspiration from various African traditions. Philips considered the functional aspect of the warriors’ uniforms, designing the neat wrap skirt and red halter/ bandeau for the quick movement and agility of the Agojie.

The addition of the small cowry shells symbolised the gifts given to successful warriors by the king with them being woven into their jewellery, armbands, headbands and pouches. Their hairstyles too were all neat and natural with various forms of braids, locs and twists. The uniforms of the Agojie portrayed functionality, androgyny and strength. When Nawi hears of the European style of dress for women, the first thing that crosses her mind is, how will she run?

Red runs deep throughout the film with the neat halters of the Agojie against their dark, lithe bodies, the thick streams of blood glistening on their spears and machetes and the red dirt through which the Agojie trained, wrestled and fought. In many West African cultures, red is a symbol of strength, spirituality, life and death. As is seen, the women were also deeply spiritual and believed in being guided and protected while they fought.

Philips, therefore, had the idea of personalising each actor’s costumes with particular signs engraved on their leather belt, with meanings such as courage or valour. This brought forward a hint of individuality in the otherwise strong collective nature of the sisterhood. As Nanisca once scolds Nawi, they never acted or fought alone, but always together, which highlights another aspect of the film, the honest and heartfelt loyalty between the women.

Nawi, a young rebellious trainee first joins, scrawny and defiant under her mentor, Izogie. Their relationship and bond truly deepen on a level of fighting for each other’s lives, with Mbedu and Lynch both delivering uninhibited performances, the echoes of Nawi’s pain ringing in the viewers’ ears and piercing their hearts at the loss of Izogie. Nanisca and Amenza too, have grown, trained and protected each other fiercely, their friendship a contrast of Nanisca’s seriousness and ferocity complementing Amenzas passion and care, each one only wanting what was best for the other.

The characters all displayed versatility, integrity and most of all, the true strength, both physical and emotional, of women with brilliant performances put on by each actress. It is rare and refreshing to see this deep passion and love shared amongst women, through the bonds of the Agojie.

The film was criticised for overly dramatising true events, portraying an ironically patriarchal society and a slave trade economy. However, the creators had no intention of covering up or altering the history of Dahomey. The focus of the film was the story of the Agojie in Dahomey, which they truly did a phenomenal job of representing. Despite this, the film was seemingly snubbed of any Academy Award nominations, bringing up issues of representation, #OscarsSoWhite.

No Black Woman director has ever been nominated for best director, and this seems to be a recurring issue when a film as phenomenal as this was ignored. Viola Davis rose from quite literally nowhere, with a poverty-stricken background with only her raw talent and hard work to rely on. Davis truly believes that the focus on the human story, those stories which are more than just reductive stereotypes, such as The Woman King, will bring about diversity in the acting industry.