Whenever a conversation on caste-based violence against women in India takes place, a common response by the majority of the public is that categorising this violence shouldn’t be based on caste, culture, religion, or ethnic lines. As one strolls, through countless testimonies of atrocities carried out on Dalit women and their bodies in the digital space, the comment sections showcase the distaste of the privileged groups to acknowledge caste as a factor in reading violence, and how its course could be altered for different women belonging to different social locations.

This line of argument is consistently produced by the privileged communities without engaging with the fact that caste-based violence is a reaction to maintaining the status quo whenever caste is challenged in any manner.

Sheetal Kamble, the author of Dalit Women: Emerging Patterns of Caste Violence, succinctly engages with the vulnerabilities of Dalit women in her ethnographic text. Kamble traces the enduring uphill battle feminists face in raising their voices against domestic abuse, violence, and sexual harassment in the workplace.

Both struggles were instrumental in shaping the Domestic Violence Bill of 2015 and the implementation of POSH in institutional spaces. However, Kamble is fierce in her endeavour to highlight the sidelining of the Dalit feminist voice. Kamble’s introduction begins with an important question: What will ensure the removal of caste-based violence against women, especially against Dalits who remain positioned between the nexus of caste and gender imbalance?

Unpacking caste-based violence against Women

Kamble’s text disrupts the belief that Dalit women are silent sufferers of caste-based violence. Her research explains the causes of continuing violence against Dalit women. She traces the historical backdrop against which the nature of the socio-religiously sanctioned violence against Dalit women can be examined. By deploying ‘violence,‘ as a site of inquiry, this book lays out the multifaceted stretch of the power structures connected with caste and gender. It details the functioning of the caste hierarchies in society.

A famous anthropologist, Louis Dumont, believed that caste functions in the Indian subcontinent through the maintenance of social order and hierarchy. Within this order, Dalit women are relegated to the most impure and disposable status. Dalit women and their community’s joyful, dignified existence are a threat to the end of caste privilege and power.

Re-centring the oppressors

Kamble’s analysis of three case studies based on communal violence situated in rural Maharashtra is a powerful attempt to invite the readers to pause and seriously address not a ‘new,’ but rather an old pattern of violence that gives impunity to the upper caste and communities of dominant caste men and continuously renders Dalit women as the ideal ‘targets,‘ and ‘subjects,‘ of caste-based sexual violence.

This book is clearly inspired by Dr Ambedkar’s analysis of endogamy, as it exposes the nuances of the power of gender that gains its legitimacy through a caste system. Kamble’s tone grows angry and demands accountability in the book on many occasions for the continuing form of invisibility, normalisation, and continuation of skewed social networks, cultural environments, political power, and economic capital that favours dominant caste men and their wrongdoings.

Kamble asks, “Why does Dalit women’s assertion provoke the dominant caste men so much so that they have to resort to extreme violence and humiliation? What does it change in the caste system?” The acronym CBVAW in the text describes how gender and caste interact; it not only serves as a reminder of intersectionality but also logically defines the reality of Dalit women and makes it tangible within our comprehension of the social system. This is an attempt to challenge the social factors that maintain that raping a Dalit woman by a member of the ruling caste is acceptable.

In addition to outlining their rights, Dalit women often emphasise the covert erstwhile untouchable practices that take place in both rural and urban places due to their assertion. Dalit women are drawing attention to these practices in order to expose the reality of violence in the context of the various patterns from which it arises.

For instance, Dalit women have on occasion discussed their love and dating experiences in the social arena in urban settings. An article written by Deepa Pawar argues that “romance is often used as a tool to harass young women from marginalized castes who are educated and employed and participate confidently in public life. When dominant caste men enter emotional and sexual relationships with Dalit women only to reject them as members of their homes and families, is it not a form of untouchability?”

Reading aesthetics of Dalit womanhood

Kamble’s text prompts a reader to engage with the question of sexual violence against women in India beyond the conventional, homogenous frameworks. By detailing the significance of engaging with the Dalit Feminist Standpoint Epistemology in chapter two, Kamble reinstates the urgency to read the everyday aesthetics of Dalit women.

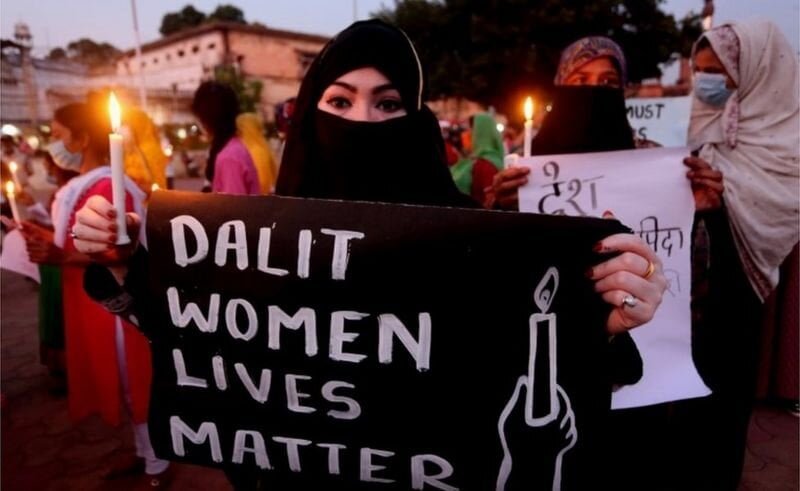

Dalit women’s lives are a constant struggle to resist caste-based discrimination and secure social justice in mainstream society by raising questions on representation, inclusion, human rights, and exploitation.

Caste-based violence against Dalit women in the ‘rural,’ and ‘urban’

Kamble’s study doesn’t keep only the ‘city,‘ or the ‘urban,’ as the centre of her research motivation. Her text uses an Ambedkarite approach that problematises the former Gandhian gaze through which we imagine the ‘village,‘ as a site of social harmony, and urges the readers to be vigilant about the constant humiliation and degradation of Dalits and Dalit women in specific villages in India.

Without engaging with the village, one cannot fully grasp Dalit women’s positionality within the socio-economic structures of the nation. Both an insider and outsider perspective is crucial for an in-depth analysis of Dalit women’s lives.

Challenges faced by a Dalit feminist social researcher

The three case studies of Dalit women in chapter three break open the idea that the field is an inviting space for all social researchers alike. The challenges faced by Kamble during her fieldwork, specifically caste-based in nature despite her own positionality and access to the community reflect that the field in India is not a plain field, instead, it is already operating at intersections of caste-class-gender-sexuality.

The terrain of knowledge production in itself is not an equal starting ground, and social researchers who come from the margins, especially Dalit feminist social researchers often end up carrying the entire responsibility for speaking for women who come from the margins in a politically correct manner as they understand the implications of language while talking about Dalit women’s lives.

Recognising varied stages of caste-based violence against Dalit women

Kamble bravely engages the reader with these nuances on her fieldwork journey. Dalit women’s negotiation with the structure wherein they are placed is thoroughly investigated in chapter four as Kamble argues, “the assertion of Dalit women, their efforts to negotiate with the village and higher-level authorities, and its violent repercussions are unique in the entire world.”

She takes this analysis of caste-based violence against women at a secondary stage forward by focusing on the role of the state actors, law and space in chapter five. The right to justice is well defined by the law within the Indian constitution, although the processes of securing social justice for Dalit women survivors of atrocities cases reflect neglegience often by the police by not filing an FIR, and framing them as ‘culprits,’ not victims. Kamble like many Dalit feminists demands accountability, and routine checks on the systemic exclusion of Dalit women from the biased attitudes of the law mechanisms and judicial systems.

In chapter six, Kamble explains the tertiary stage of violence as being separate from the primary and secondary. This clarifies how the atrocity case continues to reverberate in the life of the Dalit woman who experienced primary brutality long after the tragedy. The restoration of Dalit women’s dignity and personhood forms the basis of speaking against caste-based violence against Dalit women.

The Khairlanji massacre in Eastern Maharastra on September 29th, 2006 is kept as the main referent case for engaging seriously with CBVAW in India overall. Even after years of this massacre, one must ask: Is there a decline or fall in cases of brutal caste-based violence against Dalit women?

The latest data from the National Crime Records Bureau reveals there was a 45 per cent increase in reported rapes of Dalit women between 2015 and 2020. The data said on average, 10 rapes of Dalit women and girls were reported every day in India. Recently, Article 14 reported, “A Dalit minor from Uttar Pradesh was allegedly gang-raped by the same men twice in 44 days, and a year later, the rapists set fire to her house in Laad Kheda village, causing burn injuries to her infant son born out of the rape. An examination of the case showed the UP police ignored vital evidence and registered an FIR for the first rape more than a year later, only after the minor went to the POCSO court in Unnao.“

The entire case is not a sole example of the errors in serving justice to Dalit women especially when the evidences are also concretely present but are intentionally tampered, with and ignored by the police to support the perpetrators in such cases.

What contains within the future(s) of Dalit girls and women in India whose fathers are mostly economically struggling to make a livelihood, and those, whose mothers are engaged in daily sustenance chores, making it an easily exploitative setting for dominant caste men who wait to use these vulnerabilities to punish Dalit women and the entire community and re-instate Dalit women’s bodies as only sexual and excess? What contains within the present where they are shamelessly denied justice in the comprehensible and incomprehensible language(s)?

What happens to these cases once they appear and disappear from our view on an everyday basis? What becomes of them? Of the Dalit girls, women, and their families who face social injustice visible in the form of caste-based violence around them? How does the vast nexus of social structures respond to these constant demands to acknowledge and rectify the flaws in the system that enable caste-based violence against Dalit women?

Kamble’s text truly supports and voices to read the resistance brought on by Dalit women in chapter seven by focusing on conversion to a new religion, the search for a separate place to live, and poetry writing have all helped the community fight the erroneous caste apartheid but the beauty of her text lies in its solicited attempt to bursting the bubble of the invisibility of Dalit women’s vulnerable socio-economic position around us through a critical reading of caste and gendered struggle.

The book fills the lacunae in feminist anthropology, anthropology and sociology and social justice, and is a must-read to educate oneself on the forms of violence, and gendered struggle. Only then we can begin to improve the social world around us.

About the author(s)

Shainal Verma is a feminist research scholar at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi. She is a Writing Urban India fellow and an Institute of Critical Social Inquiry New School fellow. She writes on gender, caste, visual culture, and urban space.