“In 2020, at the peak of the agitation against CAA, my bio on the app said if you want to meet me, come to a protest. I know it must have seemed aggressive but I didn’t want to cut any corners,” said 29-year-old Aparna to FII, speaking about one of her dating application phases. The appeal that social justice politics has in people’s dating preferences is evident in the many recent articles that talk about ‘woke’ness as the bedrock of dating through mobile applications lately.

A little way away from its origins in African-American consciousness, wokeness is seen as the awareness of prejudice and a declaration against it. Increasingly used ironically, it is also supposed to entail self-reflection on the part of those who benefit from oppressive structures and is a popular conversation online.

How do we understand this current moment of conversations around intimacy and politics? How do they serve the cause of social justice in the first place? Can they affect enduring power structures such as caste or gender? Looking at the longer histories of these structures offers a starting point.

Dating in Indian cities: Intimacy and respectability

Following Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s analysis that caste is a system of endogamy, a way of controlling sexuality, much scholarship has shown that caste is sustained by maintaining several dichotomies including that of the upper and lowered caste woman. The lowered caste woman who is forced to engage in ‘defiling’ or public manual work, is stigmatised and sexualised, while the cis heteronormative upper caste or Brahmin woman in particular, is idealised for possessing a private.

Today cis women have entered the space of dating applications, especially in metropolitan cities, as autonomous individuals. In this realm of matchmaking that was previously strictly regulated, families and communities have little say. I spoke to women – particularly, young Brahmin cis women in the city of Bengaluru – to think through intimacy and the operations of caste today in cities which are painted by neoliberal narratives as modern, and therefore casteless.

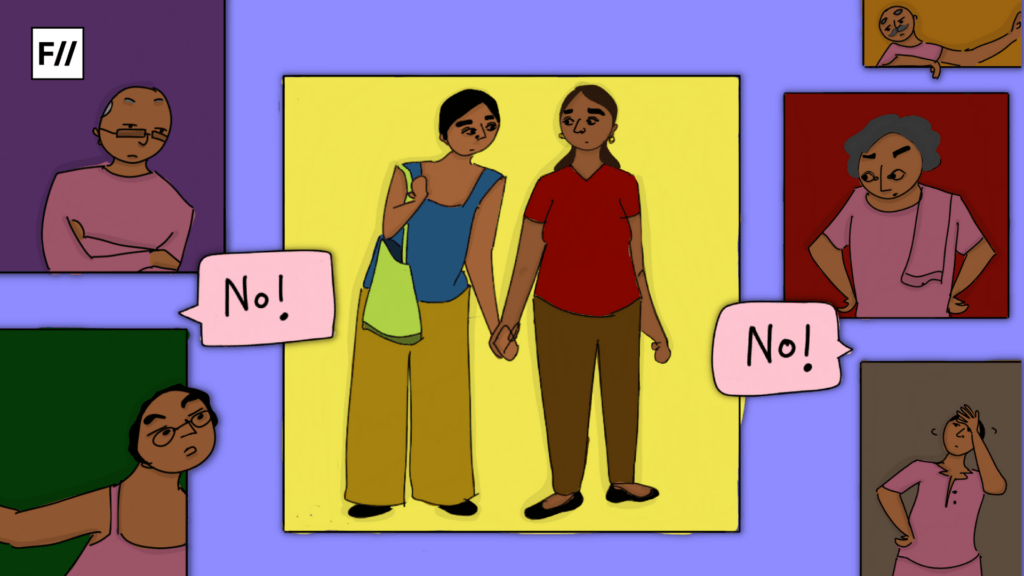

Of course, it’s tricky because a relative can recognise you. But I can avoid those areas. And as someone who speaks Kannada, cops tend to be nicer to me. I have been pulled up twice for holding hands with a guy. The first time near Lalbagh, they just asked me my name and where I’m from… they realised my family is here, even my grandparents live here. Another time they were randomly checking the phones of young people moving around in the city. They said “Oh! You’re Brahmin” and let me go. I can try to give up my caste but it doesn’t go away just like that

Sahana

19-year-old Sahana, who comes from a Madhva Brahmin family, has been navigating the streets of Bengaluru while out on dates with men or women for a couple of years now. She shared: “Of course, it’s tricky because a relative can recognise you. But I can avoid those areas. And as someone who speaks Kannada, cops tend to be nicer to me. I have been pulled up twice for holding hands with a guy. The first time near Lalbagh, they just asked me my name and where I’m from… they realised my family is here, even my grandparents live here. Another time they were randomly checking the phones of young people moving around in the city. They said “Oh! You’re Brahmin” and let me go. I can try to give up my caste but it doesn’t go away just like that.”

In fact, feminist anticaste scholars have shown that feminism itself has long rallied around the ‘safety’ of those women who choose to step out of their private spheres, while it ignored the question of those whose lives complicate the public-private binary.

Sahana and others in the study, intentionally or not, mobilise their traditional caste identity and local linguistic backgrounds to navigate intimacy. They do not simply use new resources afforded by a liberal economy or cosmopolitanism of the city. In fact, it is a well-known fact that ‘other’ bodies, whether Dalit, Adivasi, Muslim, and gender non-conforming bodies across all these axes continue to be institutionally policed and subjected to brute force in the modern day.

It is clear that those who can easily push the boundaries of “respectability” associated with caste by breaking sexual norms are those who have been systematically granted respectability in the first place. This is the context in which the current debates around wokeness in dating are taking place. Who does wokeness serve then?

Woke as in (self)aware

For those of us who are beneficiaries of oppressive systems, part of being woke is to check one’s privilege – across different axes of power. In the Indian context, one of these axes, compellingly, is caste. This means not only acknowledging how caste systematically allows savarnas or those with caste to reap benefits simply on account of their caste, but that ‘savarna’ itself refers to a few groups on top of the exploitative caste hierarchy. This is particularly popular among those in public higher educational institutions or those who have had access to social justice language via the Internet. It is these individuals in whom my curiosity lies.

21-year-old Surabhi, who comes from a low-income Brahmin family and is a student in Bengaluru, speaks about her preferences while swiping through profiles: “If they say they are apolitical, it’s a no, an immediate left-swipe. Not even liberal or moderate… Why are you sitting on the fence?” Clearly, the aversion is not just towards fascists, or as the lingo goes – sanghis – but also towards fence sitters who cannot assert their stance against dominant ideologies.

Many others have sentiments similar to Surabhi but safe to say this is a miniscule population whose dominant identity formation is desperately understudied. In the context of studying dominant identities, Robyn Wiegman asks what led to the decline of Whiteness Studies as a field. While attempting to destroy the undue value given to Whiteness through self-conscious articulations of white subjects, such studies do not achieve what they set out to as they lead to a perception of an increasingly self-knowing and empowered dominant subject.

In the Indian context, on the other hand, critical work on dominant identities that do not normalise or glorify caste is recently growing. Academics including Gopal Guru and Shailaja Paik among others have critiqued the ghettoisation of caste studies as Dalit studies because ‘upper’ or ‘touchable’ castes go unmarked in research.

In the Indian context, on the other hand, critical work on dominant identities that do not normalise or glorify caste is recently growing. Academics including Gopal Guru and Shailaja Paik among others have critiqued the ghettoisation of caste studies as Dalit studies because ‘upper’ or ‘touchable’ castes go unmarked in research. Following such critique, recent works have tried to invert the sociological gaze, tracing the smooth transition of caste privilege into class privilege through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and into the present via easy access to modern education, professional degrees, migration into cities, dominance in bureaucracy, and later, entry into the private business enterprise.

Online and offline, in academic and non-academic spaces alike, this enterprise of checking one’s privilege offers social currency and as it turns out, makes one desirable. But what does it mean for people like Surabhi to be woke and choose dates who are like-minded?

29-year-old Siri, who comes from a Madhva Brahmin household and works in the space of art and archiving, talks about what allows for intimacy with dating app matches: “I joke with T (a Smartha Brahmin) that half the reason I find him attractive is that he doesn’t wear a janvaara (a thread worn as an identifier by brahmin men). He fights the rituals at home and it becomes a point of connection for us.” The irony is not lost on her, as she says: “I know what this means… I’m probably only connecting with people from the same caste location.”

The intimacy here lies in distinguishing themselves from their orthodox families. It does mean choosing someone who is not practising caste in the ritualistic sense, but from a similar position in the caste hierarchy. If studying dominant identities and their sustenance is to bear any fruit, we need to probe these ‘similar positions’ in greater detail, beyond terms like ‘savarna’.

Unpacking the internal hierarchies of savarnas

25-year-old, Janhavi, who works as a researcher in Bengaluru, comes from a mixed-linguistic Brahmin household. She laughed about her father insisting on finding a Hindu atheist, even if not from their ‘community’ or jaati (caste). She finds it amusing especially because he frames this as a compromise.

Making a case for single caste studies, Ramesh Bairy has argued that terms like upper caste, though indicating a common complicity in an unequal system, assume more coherence than exists within the graded system of caste. Other terms like general category or OBC, proposed by the state, speak little of internal structuring.

Making a case for single caste studies, Ramesh Bairy has argued that terms like upper caste, though indicating a common complicity in an unequal system, assume more coherence than exists within the graded system of caste. Other terms like general category or OBC, proposed by the state, speak little of internal structuring.

While the term ‘savarna’ is in currency at the moment, jaati differences play out strongly in experiences of discrimination within homes and outside. This is apparent in the case of Surabhi’s uncle who married a non-Brahmin upper caste woman and whose children are seen by the family as undisciplined because their mother is “incapable of bringing them up with their values”.

Contrast this with 24-year-old Sharanya’s understanding of caste. Sharanya, who comes from a Brahmin family that migrated to the city only in her parents’ generation, works in the Kannada film industry. She identifies the men she has dated with surnames like Gowda and Shetty as upper caste since they are all “very much like” her in terms of social capital and “much better off in terms of money”.

However, her understanding is at odds with governmental categorisation, and even non-Brahmin movements in Karnataka. The Vokkaliga community (that sometimes uses the surname Gowda) has deep cultural differences with Brahmins and has been known to challenge the Brahmin dominance in the state. With changing state policy on reservation, demands by caste associations, and a lack of numerical data on representation, the Brahmin-Vokkaliga equation continues to be a tense one.

In a different vein, Naveen Soorinje talks about the dominance of Bunts (who are categorised as OBC and some of who use the surname Shetty) along with Brahmins in the leadership of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh today in maintaining a Hindu-Muslim binary that clouds the question of caste in the coastal regions of Karnataka.

A close look at any caste group in the specific context of its region and historical trajectory can provide insight into the contradictions in the making of community identity. This will help us prise open how intercaste alliances of different forms are working to either hold caste in place or destabilise it.

A close look at any caste group in the specific context of its region and historical trajectory can provide insight into the contradictions in the making of community identity. This will help us prise open how intercaste alliances of different forms are working to either hold caste in place or destabilise it.

But the question that remains is how romantic or sexual relations imagine and shape caste, especially now when they are accentuated by digital technology which is also sold to us as modern and hence, democratic.

Dating and social change

The connections made on dating apps with people who are ‘compatible’ may easily convert into marriage alliances, consolidating caste networks and financial capital. However, even in the space of dating, these preferences have implications for the sustenance of caste. For instance, these connections made within caste norms become a support system in the city where one learns about job openings in the corporate sector which is untouched by reservation policies in the first place.

So, would dating differently destabilise these networks? Disha KR writes of the dilemmas of Dalit women in inter-caste relationships as they struggle alone with desire and power without models around them to turn to. Besides, the violence and discrimination meted out by Brahmins and other upper/dominant castes within such relationships have been documented by Christina Dhanraj and more recently, Akhil Kang, Ravikant Kisana and Deepa Pawar.

For those of us with social media and academic lessons on social justice, saying the right things even in inter-caste dating encounters or relationships may be possible. Woke language, however, can barely cut through the constant tug between desire and prejudice. Without a community that offers acceptance and support, these relationships are bound to be ridden with challenges.

For those of us with social media and academic lessons on social justice, saying the right things even in inter-caste dating encounters or relationships may be possible. Woke language, however, can barely cut through the constant tug between desire and prejudice. Without a community that offers acceptance and support, these relationships are bound to be ridden with challenges.

Questions on caste in intimacy and desire are easily dismissed as matters of compatibility that comes from already existing proximity in spaces of education, work and leisure. Dating happens to be just one of the many sites where caste can be captured in all its dynamism. All this talk of dating and matchmaking then needs to break open how we occupy these spaces, all of which are today infused with digital media and marketed to us as neutral, secular, and modern.