For someone not familiar with the sheer diversity of music historically sung and produced by the people belonging to various communities in Punjab, Bhangra music in Bollywood films and songs released as part of popular albums by contemporary diasporic Punjabi singers, such as Diljit Dosanjh and “Harrdy,” Sandhu, become representative of “Punjabi,” music. The various traditions that characterise the music of Punjab are numerous, with one of the most prominent strands constituting folk traditions.

Before, folk songs (or lok git) were sung only for a limited audience by professional performers who were hereditary singers, and thus, claimed a monopoly on the performance of folk songs in their respective social groups. They considered it their birthright to sing these folk songs, and strict social norms of propriety prevented others from venturing into these professional spaces which was a source of livelihood for the performers. These professional artists were mostly men.

Apart from singing professionally, singing folk songs was also an informal, participatory activity. During important events, such as those of death in the family or a wedding, these songs were sung by members of the group for themselves—and other people present on these occasions. They were sung mostly by women. Without vocal training, without the aid of instruments, and with only the rhythms and the song texts, they were sung loudly, in unison. Sung in any manner, the songs were (and are) a crucial part of the Punjabi culture.

Within this context, several voices were composing folk songs for a wider audience around the mid-twentieth century. The music industry with its tendency to democratise and popularise music through recordings and cassettes brought to the fore prominent singers, such as Surinder Kaur and Prakash Kaur, who commercialised folk music.

This allowed individuals from different castes, and especially women, to perform in professional spaces and bring folk music to larger audiences through radio and audio. However, certain folk artists performing commercially were not accepted by either their families or other communities because of their encroachment into such spaces.

For instance, Lal Chand was a noted Punjabi folk singer. He belonged to the lowered caste, however, through his stage name, “Yamla Jutt,” he projected himself as a Jatt man belonging to the upper caste group of landowning Punjabis who wield the most economic and social power in Punjab.

Another example is that of Surinder Kaur. Her family considered women singing anything apart from devotional songs as a “dirty,” act. Even though her husband influenced her considerably in her career as a singer, he did not allow her to sing “dirty,” songs that may contain sexual and “questionable,” themes, because of which she didn’t perform at weddings.

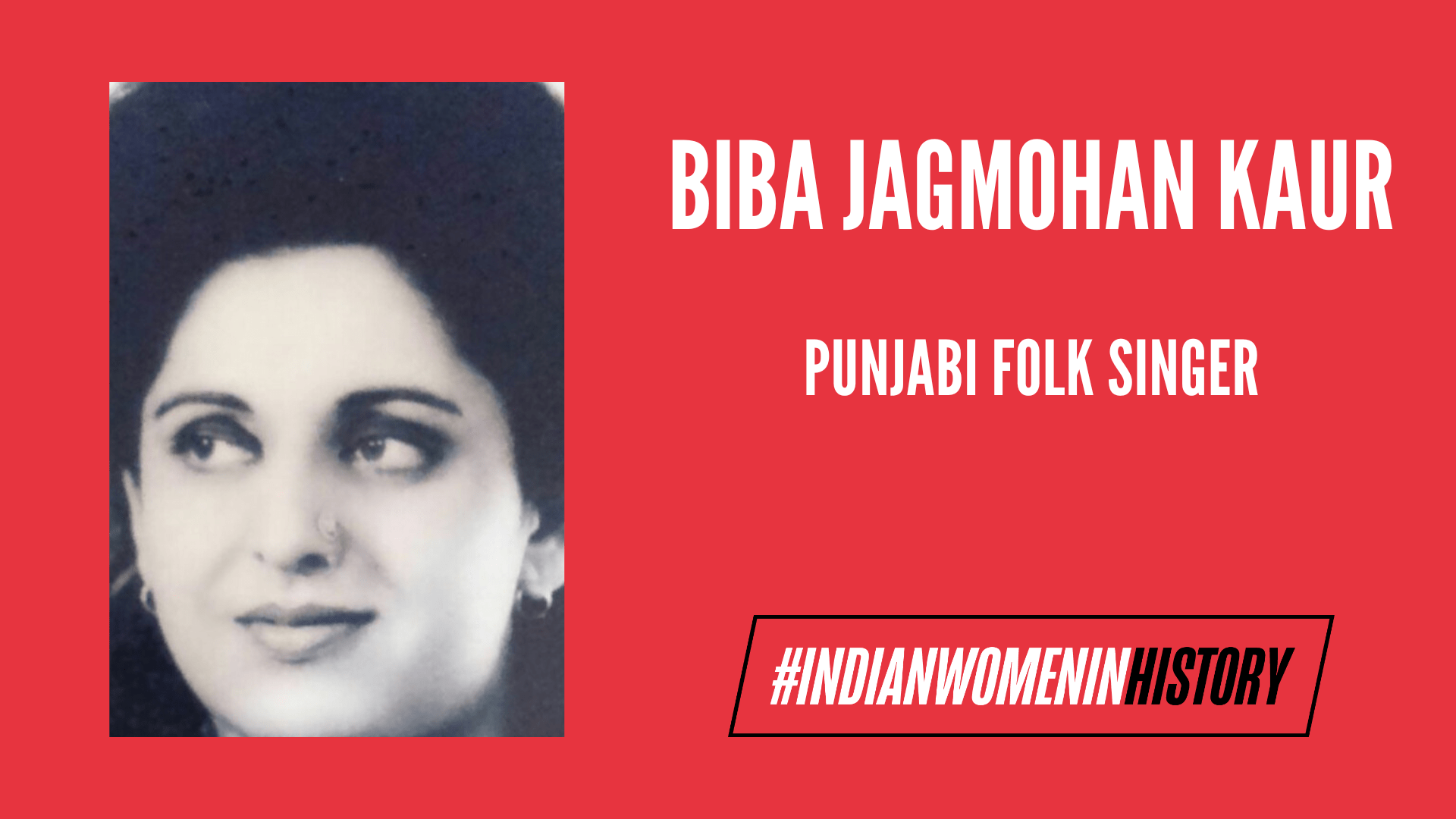

Later in the 70s, when recorded folk songs accompanied by different instruments and melodies were thoroughly enjoyed, Biba Jagmohan Kaur, along with her husband K. Deep, became a household name in Punjab.

Biba Jagmohan Kaur was born in 1948 to Gurbachan Singh and Parkash Kaur in Pathankot, Punjab. Before choosing to pursue music full-time, she worked as a teacher. Departing from the tradition of singing devotional or nationalistic folk songs, she sang about the minutiae of everyday life, which people of all classes could identify with, making music more accessible.

Gibb Scheffler, a professor of music, articulates this increase in identifiability by a larger audience as follows:

“The style and content of Punjabi popular music of the 1970s to 1980s were markedly different from what preceded it. Its texts were decidedly more piquant than those of the nationalistic folk revival, often presenting risque scenarios. The vast majority were newly composed. The music as well as new and innovative. It used the raw sound of village musicians, to which were added some Western instruments, set in snappy arrangements. The most successful composers in this vein were K. S. Narula and Charanjit Ahuja. Through the 1980s this sort of commercial “country,” music, Punjab’s equivalent to Nashville, held wide appeal with rural Punjabis. Its themes and presentations appealed especially to the working class and the provincial. Indeed, consumed by and performed by lower socio-economic groups, some aspects made it appear to be “low class,” to the more genteel.”

Aarnav Tewari-Sharma delineates Bibaji’s journey in music that made her an accomplished singer and beloved by all her listeners:

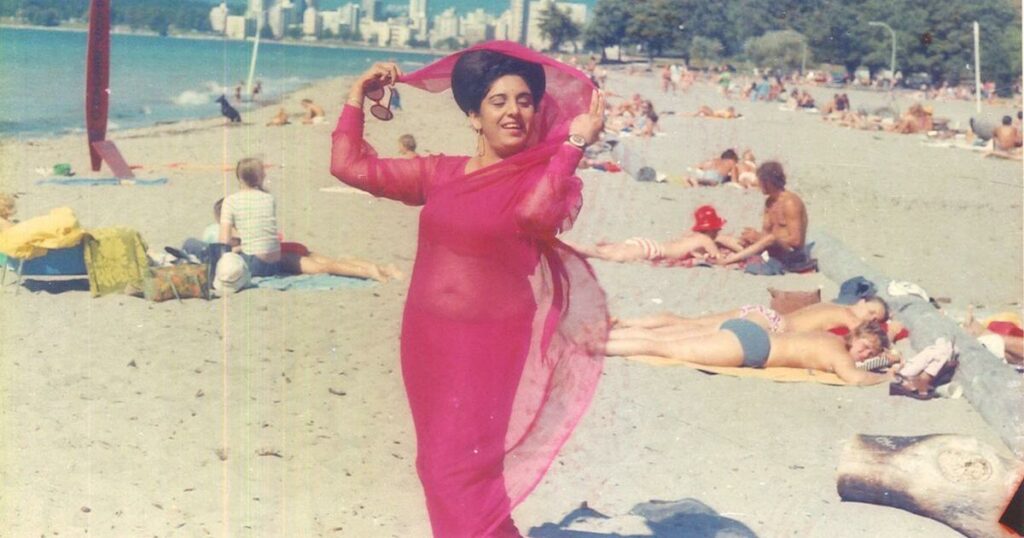

“She continued recording and performing around the world – in rural and urban Punjab, in Britain and Canada, in the Doordarshan Punjabi studios in Jalandhar, and the BBC studios in New Delhi. Her last album came in 1998, a year after she passed away. By then, Punjabis had been united in their love for the blunt, wonderful Biba Jagmohan Kaur.”

One extremely touching Mirza-Sahiban has been performed by Biba Jagmohan Kaur. Along with Heer-Ranjha and Laila-Majnu, the story of Mirza and Sahiban is one of the most popular love stories to originate from Punjab. Mirza Jatt fell in love with Sahiban, however, the love was forbidden. Sahiban’s family found out. Mirza and Sahiban eloped on the former’s horse, Bakki. Mirza and Sahiban died a tragic death, where the former was killed by Sahiban’s brothers, and Sahiban died by falling on the same arrow.

Kawan Ve Kawan communicates a sense of profound grief and loss. The song is about separation caused by destruction and violence where the loved ones are crushed and forever lost. A Google search would render “Baba Ve Kala Maror,” as one of her most popular songs which she sang with K. Deep.

The duo is known for their boisterous, risqué, and playful style. “Baba Ve Kala Maror,” with its sexual undertones, is representative of their style. It portrays playful flirting back and forth between a driver and a young woman who are hurling tongue-in-cheek responses to one another. “While pushing, I get breathless,” she claims while heaving in the song.

Biba Jagmohan Kaur, a singer who has firmly established herself in the folk tradition, has performed an eclectic array of songs, ranging from devotional to romantic, from lustful to melancholic. Even though she is fondly remembered by elderly people, there is little awareness of her music among the youth. While her fate is not unique, the fact is extremely telling of the necessity to document and preserve songs sung by noteworthy folk singers.

The dearth of data, documentation, and information in English (since English is a common language spoken by a good majority of people in India and abroad) on such folk artists in the age of the internet makes them undiscoverable to potentially interested listeners of their art.

This is a common disadvantage folk singers experience despite the availability of their music on YouTube and other platforms. But, there is so much on the internet. Something to seriously think about would be what would make remarkable folk artists more visible. Is there more research required? Or perhaps newer renditions of the older songs by popular artists, leading their fans to discover the original songs?

About the author(s)

Shakti (she/her) is an English major and an aspiring tea sommelier. She loves reading poetry and drama and can be found with a Kindle most time. She intends to become a teacher of humanities and is passionate about literature, films, politics, and history. In her free time, she has been caught watching cringe content, however, she fervently denies these claims.

Excellent research and analysis! You have set a platter right in front of your readers of the significance of documenting and promoting the music of folk artists. Your suggestions for research and newer renditions by popular artists show a deep understanding of the issue. Well written! Very engaging! Thank you for the offering the read..