Trigger Warning: This article mentions gender-based violence and rape.

In May 2022, the division bench of the High Court delivered a split verdict on the criminalisation of marital rape. The Supreme Court will begin to hear petitions on the same again later this month (July 2023). This issue is only one facet of the prevailing narrative built around the question of women’s safety in India. The present opinion held by most Indians is that women’s safety is in their hands, and they must “make” the choice to “be safe” by limiting their movement outside of their homes and workplaces.

However, the adoption of this overly simplistic, paternalistic and protectionist approach is insufficient to counter the epidemic of gender-based violence that India is facing. This attitude results in the creation of a false dichotomy, showing the public space as ‘hostile’ and the private space as ‘safe’. It has one simple flaw- it denies the existence of ‘private violence’, or violence that occurs at the home.

Understanding the public-private divide

In sociology, one way of looking at the community is by dividing life into two spheres, the public and the private. Public life consists of government institutions and paid employment, political and economic issues, and is governed by social norms. Private life consists of the home, domestic work, and intimate relations between the family.

This view is also a historically gendered one- women were relegated to the private sphere while men were in charge of the public sphere. It leads to more related assumptions- women are responsible for the family, and meant to stay home, while men are meant to work and perform ‘productive, wage-earning labour.’ This divided perspective of life is actually a lie that conceals women’s subordination and perpetuates gender inequality. In reality, what we deem as ‘private’ has political consequences. Or put in another way, the ‘personal is political.’

The narrative of safety and violence in the public sphere

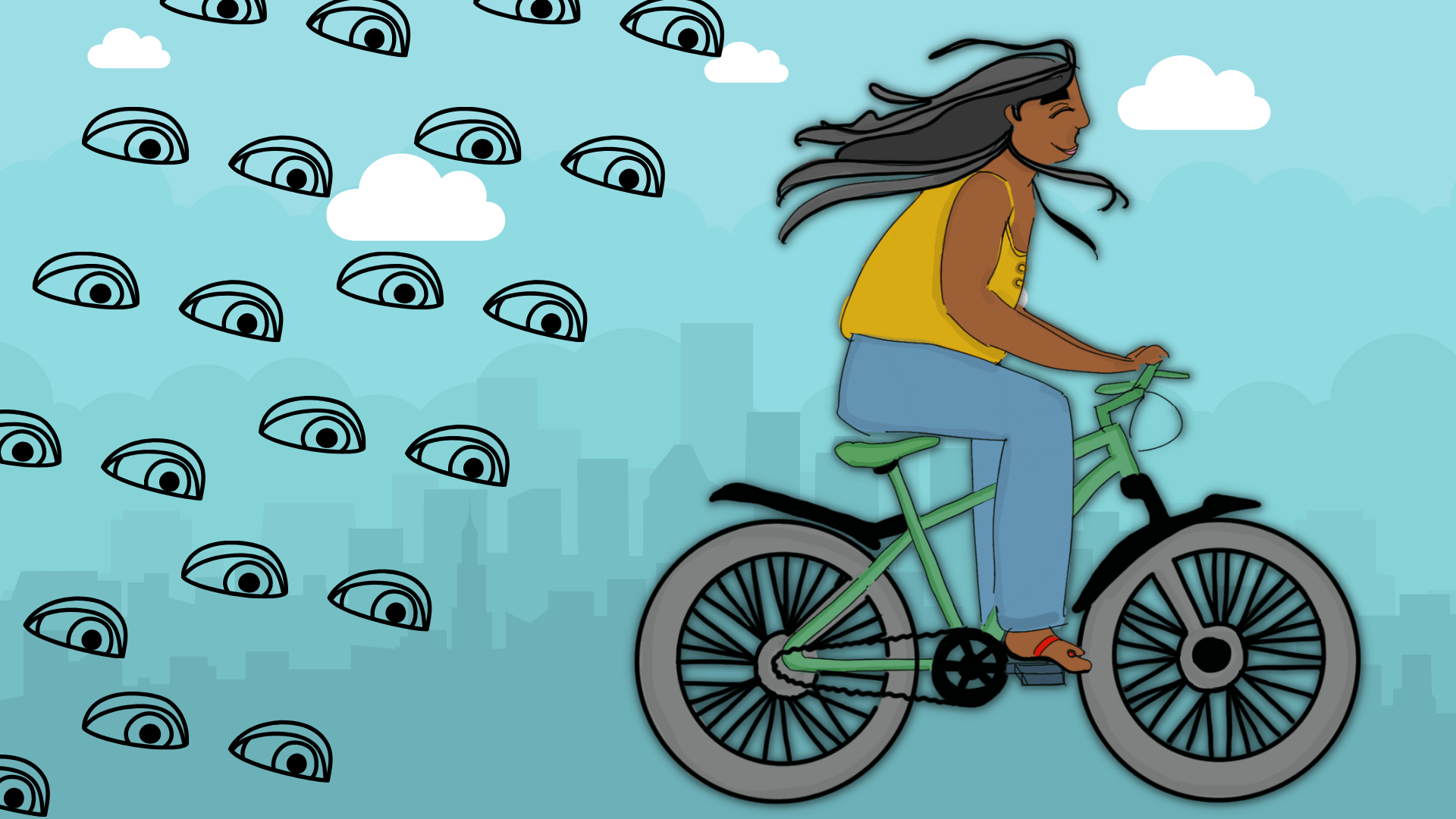

In the public sphere, the narrative of safety and violence consists of fallacious binaries: ‘private versus public’, ‘rational versus risky’ where one is viewed as the antithesis of the other. The mere perception that the outside is dangerous limits significant numbers of women from stepping out.

If and when women finally do manage to access the public sphere, their safety while existing there is conditional. One, they can’t go outside without a legitimate purpose- such as shopping, school or work. Second, they must also ‘negotiate with the public space’ to be ‘safe’ by modifying their walk, their appearance and gaze to ‘minimise’ the risk of violence, that is, women must exhibit their ‘respectability and morality’, because only ‘good’ women will be protected.

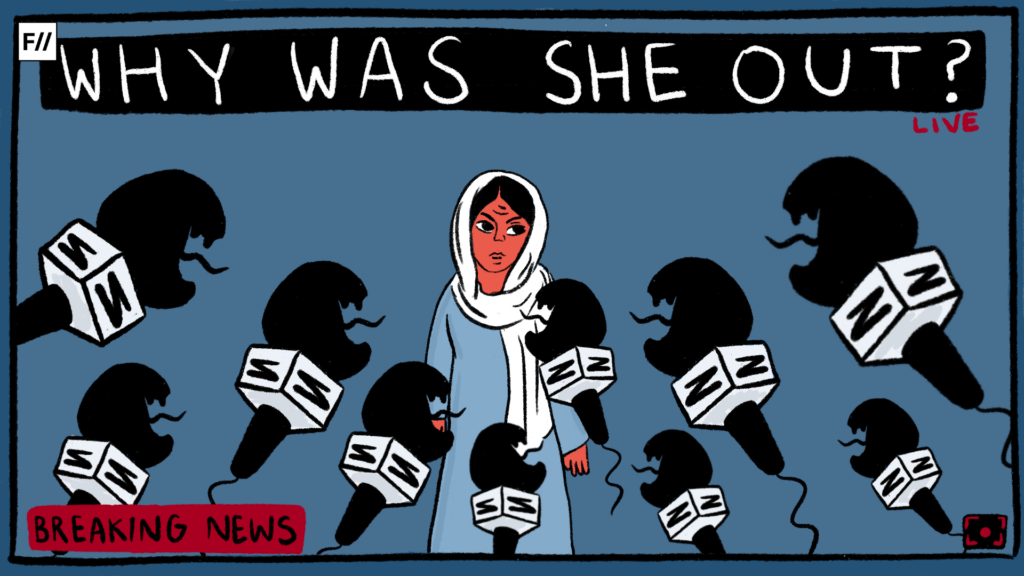

If and when women finally do manage to access the public sphere, their safety while existing there is conditional. One, they can’t go outside without a legitimate purpose- such as shopping, school or work. Second, they must also ‘negotiate with the public space’ to be ‘safe’ by modifying their walk, their appearance and gaze to ‘minimise’ the risk of violence, that is, women must exhibit their ‘respectability and morality’, because only ‘good’ women will be protected. Even despite these so-called ‘precautions’ being taken, when gender-based violence does inevitably occur, it is seen as the women’s fault, that is, they must have done something to instigate the attacker, a common rape myth termed as ‘victim precipitation belief’.

The emphasis on good women alone being protected can be seen in the callous attitude adopted by the police when responding to complaints of harassment by female sex workers, who are not seen as “good, respectable women” in the patriarchy’s eyes. Law enforcement authorities can sometimes be the biggest perpetrators of violence, especially against women from religious minorities and trans persons, but they receive no backlash for this. This also speaks to the lie of ‘safe’ violence by authorities.

The narrative of safety and violence in the private sphere

Violence in the home, or private violence, is a different animal from public violence because women are supposed to be ‘safe’ here. The abuse at home is not only physical in nature, it can be financial, emotional, etc, where power is exerted on the women to control their choices and behaviour. The pressure to keep quiet about the occurrences at home is not just to maintain the illusion of safety, but also to maintain the reputation of the family.

Despite such silencing influences, some kinds of violence at home are more visible than others- such as abuse in the marital home is more talked about than abuse that women face in their natal homes. The reality however is that the majority of Indian women who experience domestic violence do not report it. This situation only worsened during the pandemic, when many working women were forced to return to unsafe homes.

Despite such silencing influences, some kinds of violence at home are more visible than others- such as abuse in the marital home is more talked about than abuse that women face in their natal homes. The reality however is that the majority of Indian women who experience domestic violence do not report it. This situation only worsened during the pandemic, when many working women were forced to return to unsafe homes.

Post Covid-19, with the return of relative normalcy, the status quo has resumed. The overall focus is on keeping women inside, limiting them from utilising public space freely. If women reject this ‘rationale of safety’, then obviously violence will happen- so it’s posed as a choice to women, i.e. (i) to go out and risk danger, or (ii) stay safe inside.

This seemingly altruistic attitude of protecting women’s well-being is only a sham, to ‘preserve’ women’s sexual virtue, and keep the family’s resources protected from passing into hands deemed ‘undesirable’. Families will exert violence on their own children to adhere to social boundaries which reinforce conservative caste, class and community structures. We can see the proof of this by the number of Indian women who are harassed by their families because they dared to marry across the lines of religion, class, caste, ethnicity, etc.

The spectre of honour killings, persecution under India’s love laws, ostracization from the family, and even being unable to find safe housing has made India’s small number of cross-community marriages even smaller. What further remains unsaid is that in the private sphere, women will always be under the ‘domain’ of the patriarch and thus under constant surveillance.

The spectre of honour killings, persecution under India’s love laws, ostracization from the family, and even being unable to find safe housing has made India’s small number of cross-community marriages even smaller. What further remains unsaid is that in the private sphere, women will always be under the ‘domain’ of the patriarch and thus under constant surveillance.

When stories of violence do escape the private sphere, the women are asked to justify the violence in a place that is always ‘safe’, such as Battered Women Syndrome, characterising women as ‘mad, bad or sad’, again delegitimising their agency to act.

Indian laws support the false binaries of this public/private divide, and thus the grey spaces around these categories are ignored. One of the major reasons marital rape was not criminalised is because it occurs in the home, which is a ‘private space’. In this way, the law supports this false binary by not criminalising it, despite the harm caused to the woman by this denial of their right to assert their bodily and sexual autonomy.

The selective glorification by the media

The media plays an important role in public perceptions of safety and violence in Indian cities. By making the ‘possible risk’ seem bigger than the ‘actual risk’ of stepping outside, it contributes to reducing women’s access to public space. It is also extremely caste and class-biased.

A 2019 report by Oxfam India which reviewed representation in major Hindi and English news media channels revealed that the Indian media is dominated by upper caste individuals, whose biases are reflected in the topics chosen for reporting, as well as the manner in which information is conveyed, especially incidents of gender-based violence.

A 2019 report by Oxfam India which reviewed representation in major Hindi and English news media channels revealed that the Indian media is dominated by upper caste individuals, whose biases are reflected in the topics chosen for reporting, as well as the manner in which information is conveyed, especially incidents of gender-based violence.

Stories involving affluent people are given more coverage- e.g. no attention was paid to the policemen who raped poor rag-picker girls in Mumbai. Perceived ‘respectability and virtue’ also play a role in how an attack is reported. If it happened to a ‘bad’ woman, she is seen as asking for it. English news media also suffers from an urban ‘people like us’ editorial bias.

Ways to address these various narratives of safety and violence

Whenever we talk of safety, the conversation cannot just be restricted to outside violence- we must also think of the familial and societal restrictions that act on Indian women. And when one steps outside, we need to adopt an intersectional view that challenges the bias of the media- and question them- is the city safe for women from all spheres of life? For women from minority communities, lower socio-economic sections of society, gender non-conforming persons, etc.

What would a gender-neutral urban space look like? How would it differ from the current state of the city? What small changes can be made now to promote women stepping outside, as well as promote their safety? Some measures can be more well-lit streets, building and maintaining more toilets in public spaces, and increased access to safe public transport.

Shilpa Phadke and Sameera Khan released a book, ‘Why Loiter? Women, & Risk on Mumbai Streets’ in 2011, encouraging women to access urban public spaces. Thirteen years on, this movement is still ongoing, with small groups of women holding events all across the country, passing the torch on year after year.

Shilpa Phadke and Sameera Khan released a book, ‘Why Loiter? Women, & Risk on Mumbai Streets’ in 2011, encouraging women to access urban public spaces. Thirteen years on, this movement is still ongoing, with small groups of women holding events all across the country, passing the torch on year after year. In 2022, a team of women held a session of Antakshari in the Mumbai metro, asking other women to join them in confidently taking up public space, in a visible manner. This inspired similar movements in Delhi, Jaipur and even Pakistan. For example, the #Girls at Dhabas movement.

Measures for women’s safety by the Indian police force traditionally always involve increased surveillance, but instead of addressing the symptom, we should look at the cause- the social, economic, and geographical causes that make women feel unsafe in the first place.

About the author(s)

Aadya Gupta is a fifth-year law student at Jindal Global Law School. Her interests lie in the topics of gender and intersectionality studies, environment law, and public policy.