Trigger Warning: This is a review of the book ‘The Third Eye and Other Works: Mahatma Phule’s Writings on Education’ and mentions institutional murder.

At present, India is going through a transformation within education as it isn’t headed in a progressive direction. On one hand, the distressing number of students losing their life to caste-based discrimination within prestigious educational institutions like IITs is on the rise. On the other hand, the news has been concerned regarding the removal of chapters (or parts of chapters) ranging from core scientific ideas like ‘Evolution’ and ‘Periodic Table’ to India’s history and understanding of politics with topics like ‘Democracy and Diversity.’

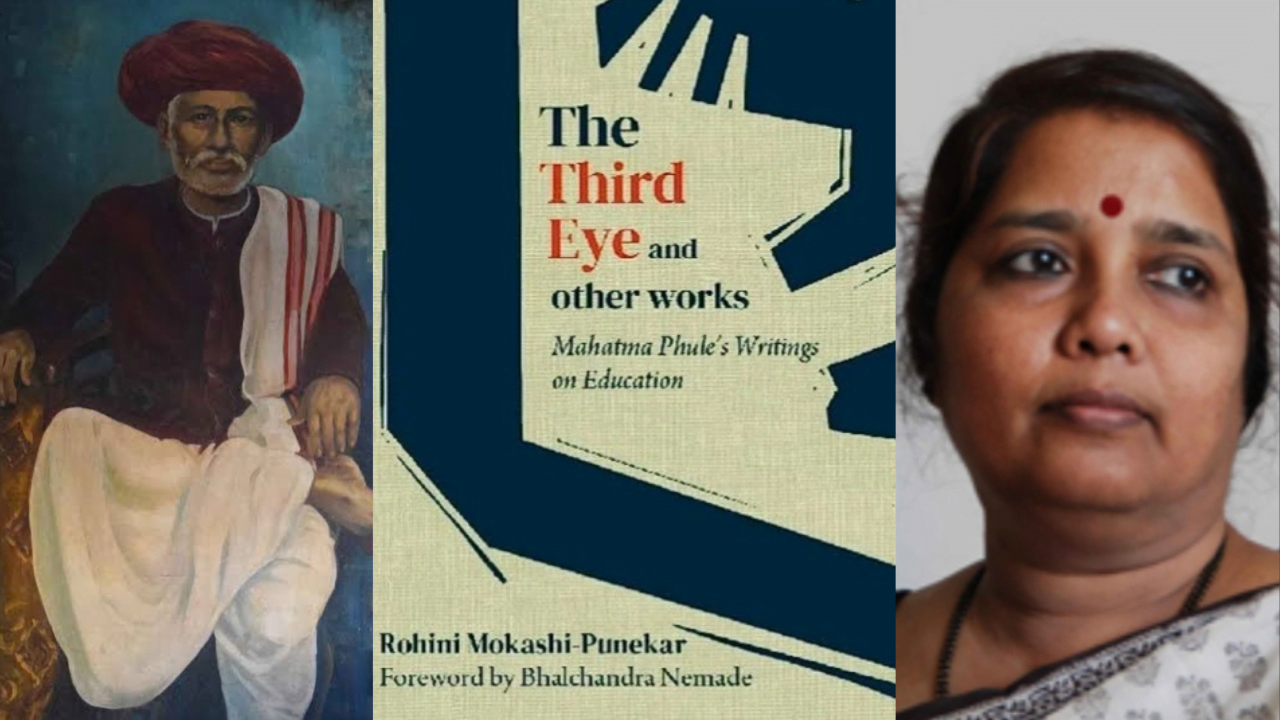

Rohini Mokashi-Punekar’s The Third Eye and Other Works: Mahatma Phule’s Writings on Education is a timely reminder of the transformative power of education, especially for oppressed sections and women in the society. Mahatma Jyotiba Phule, along with Fatima Shiekh and Savitribai Phule led the cause of gender and caste reform within India through education. They firmly held the belief that education democratises knowledge and has the power to bring self-awareness.

It is crucial to revisit the radical transformation that the education system has gone through in India not only in terms of what is being taught through the curriculum but also in terms of what shape education’s purpose is taking up.

Mahatma Phule’s idea of inclusive education as the key to social change

Rohini Mokashi-Punekar’s The Third Eye and Other Works: Mahatma Phule’s Writings on Education is a timely reminder of the transformative power of education, especially for oppressed sections and women in the society. Mahatma Jyotiba Phule, along with Fatima Shiekh and Savitribai Phule led the cause of gender and caste reform within India through education. They firmly held the belief that education democratises knowledge and has the power to bring self-awareness.

This tremendous translated work features two of Mahatma Jyotiba Phule’s seminal works that argue the importance of education as a tool for social change. The play Tritya Ratan (or The Third Eye) and the poetry Vidyakhatyateel Brahman Pantoji (Brahmin Teachers in Education Department) are the crucial works that are translated in the book. Along with this, the preface written by Mahatma Jyotiba Phule for his most well-known work Gulamgiri (Slavery) is also included. The preface deals with Phule exhorting the British government to fund the education of the lower castes. Lastly, his address to the Education Commission in 1882 is also a part of the book.

When we look back at the transformational history of education in India, the work by the Phules along with the likes of Fatima Sheikh is unparalleled, as they were pioneers in making education inclusive and accessible. The trio is already credited and celebrated for opening the first schools for lower castes and spearheading women’s education even after receiving severe backlash from the society. This volume on Phule’s work also deftly engages with these issues, while also extending to other social evils which were/are a deterrent to education including child marriage, sati, brahminical hegemony and discrimination against women and persons from marginalised castes.

The significance of Mahatma Phule’s Tritiya Ratna

Through the play Tritiya Ratna, Phule taps into what the British did in a more empowering sense, discussing the English rulers’ sense of justice and their kindness towards the downtrodden people of India. It is also here that the Christian Missionary comes up, elucidating upon the way education was central to social mobility and upliftment.

At the intersection with education, lies the questions around caste and gender, spread throughout the work. While all these details and specifications can be discussed here, it is crucial for the reader to go through them situated within the wider context of the time which reflects the structure and politics around education prevalent during that time as well. It is also a unique play featuring a myriad of voices from a Brahmin, a working-class Kunbi farmer, an oppressed housewife, to a Christian missionary and a Muslim. It is also interesting to note what reactions would the play invite if it were staged during the time it was written or even today for that matter.

The political uses of poetry and troubles with translation

The second text Vidyakhatyateel Brahman Pantoji (Brahmin Teachers in Education Department) is unique in its approach as it is composed in the traditional rhyme, where the translator used rhyme and metre while translating from traditional Marathi Poetry. As with other texts and works that are situated in a different context, it’s not always easy to translate meanings through a language which might be ignorant of those realities. Here, the translator Rohini Mokashi-Punekar has written a short note regarding the difficulties they faced and at the same time, situating their work in reference to the texts they have used directly for this body of work.

The poetry-based text dives into the well-established indigenous system of basic education which was prevalent during that time – the private schools which were run by Brahmins. It also introduces the readers to Powada, an oral and performance-based genre of poetry. It was originally performed by the Dalit community belonging to the Gondhal caste.

The poetry-based text dives into the well-established indigenous system of basic education which was prevalent during that time – the private schools which were run by Brahmins. It also introduces the readers to Powada, an oral and performance-based genre of poetry. It was originally performed by the Dalit community belonging to the Gondhal caste.

The powada translated in this book is a realistic portrayal of the rural environment and its intrinsic connections to larger oppressive structures at the macro level. It opens with a moving evocation of the hardworking marginalised caste parents grieving the lack of access for their children to schools and goes on to expose the double standard of Brahmin teachers and the ways they practise caste-based discrimination.

Some of the lines which scathingly critique Brahminism and shows the double standards are as follows:

“The Pundit is patient with Brahmin kids,

Repeat lessons and correct their slips.

A terror when a Shudra child trips,

The Pundit rains blows and slaps his cheeks.”

It also becomes important to reflect upon this in the present time for three reasons provided in the book – the conditions of the 19th-century education system unfortunately in some ways resemble today’s conditions, there has been a consistent erasure of Phule’s contribution and ideas, Dalit Literature as a discipline is seen in certain ways which the translator cites as being unhistorical. Keeping in mind these three reasons signifying a greater need for reflection, this book is also an attempt to historicise the importance of a Dalit literary past.

The long, daunting, continuing journey of educational access

The sixth section of the book titled Situating Phule within the History of Education in India is perhaps the stronghold of the book. While the literary works, their translations, and specific sections and prefaces add to the context while also supplementing the radical potential of literary works which require deeper understanding today; this particular chapter ties in all the threads in a neat way. It brings policy, government interventions, histories, and lived experiences together to portray a clearer image of how India’s educational policy was shaped by different factors.

With a particularly deep insight into colonial policy and the roles of Christian Missionaries, the chapter is a testament to the power of education and Phule as an inspiring force.

The closing section is the Memorial Addressed to the Educational Commission where Phule discusses various aspects of education from primary education to indigenous schools to requesting the Educational Commission to sanction measures for the spread of female primary education.

Rohini Mokashi-Punekar’s The Third Eye and Other Works: Mahatma Phule’s Writings on Education is a timely reminder about the path that education has traversed to be a marker of hope and emancipation for the oppressed. While the core thoughts and ideas of the Phule-Ambedkarite approach to education are well known, it’s the details of the context and the language which is missing that shine in this book.

Education as we know today is undergoing multitudes of changes and transformative shifts. Unfortunately, most of them are aligned with commercialisation, the introduction of the digital and also catering to the Hindu nationalist ideology. In such times, Rohini Mokashi-Punekar’s The Third Eye and Other Works: Mahatma Phule’s Writings on Education is a timely reminder about the path that education has traversed to be a marker of hope and emancipation for the oppressed. While the core thoughts and ideas of the Phule-Ambedkarite approach to education are well known, it’s the details of the context and the language which is missing that shine in this book.

The book involves a complete translation of some of Phule’s work, which itself has been done for the first time. The question of education, caste, gender and inclusivity is at a critical state within Indian Educational Institutions as we are entering a period of irrational removal of syllabi, removal of autonomy, institutional murders based on caste and gender discrimination, and an increasing push for privatisation. It is pertinent that we go back and look at the linkages between quality education, employment, and the aspiration for upward mobility that modern education promises.

The Third Eye and Other Works: Mahatma Phule’s Writings on Education is a much needed reflection to assess the deteriorating state of education as a way for emancipation for the marginalised groups, especially marginalised castes and women in India. It places the role of education in what Rohini Mokashi-Punekar calls a “subaltern assertion, and the centrality of education to the history of subaltern protest in India.” Although it is a valuable work for anyone engaged with the ideas of education in India, Dalit literature and/or subaltern studies, it is a must-read work for everyone to understand the shifts in education from colonial times till today, and what role caste and gender have played.