Pointlessly provocative for the conservatives and unabashedly intelligent for the queers, the Messiahs of the Internet remain divided over the phenomenon that is Andrea Long Chu. If there could be any consensus to exist, it is this: the woman sure does know how to make a mess.

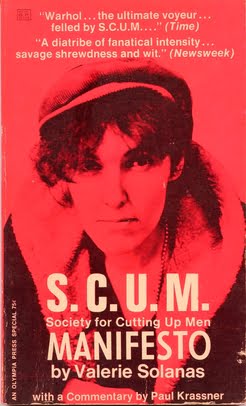

In her debut essay published in 2018, aptly titled “On Liking Women,” Andrea Long Chu dives headfirst into the world of desire, identity, and desired identity. Through her analysis of Valerie Solanas’ SCUM Manifesto and historiography of the feminist movement, Chu argues that the age-old question of ‘to be or not to be,’ is more fittingly replaced by ‘to want or not to want,’ instead.

Feminism is rad!

To use the work of a ‘radical feminist,’ in order to theorise transsexuality should be an odd choice, particularly for a lesbian, trans woman. After all, the birth of the trans-exclusionary radical feminists (TERFs) has largely been associated with primarily the SCUM Manifesto, and later what is now termed ‘second-wave,’ feminism.

However, Andrea Long Chu deconstructs paragraphs of the text to translate its message into something that looks wonderfully transgressive. Consider the beginning of the Manifesto then:

‘Life in this society being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and destroy the male sex.’

A younger Chu exclaims to have found a sort of sanction for her transness in these lines, which she explains to be a repudiation of maleness simply because it is aesthetically ‘boring.’ Chu challenges the contemporary understanding of ‘woke,’ feminist discourse, which attempts to posit its identitarian politics as ‘trans-inclusive,’ and therefore superior to the waves of feminism that preceded it.

Chu challenges the contemporary understanding of ‘woke,’ feminist discourse, which attempts to posit its identitarian politics as ‘trans-inclusive,’ and therefore superior to the waves of feminism that preceded it.

This, according to Chu, is prescriptive of the past. The current discourse that seeks to categorise feminism into neat waves erases the fact that contrarian discourses have always existed. To display this, Chu analyses and argues that the SCUM Manifesto, with its tongue-in-cheek humour, actually allows for transness to be understood as an aesthetic phenomenon. In saying so, Chu claims Solanas’ radical feminist text can actually be interpreted to also say that all men are closeted trans women.

Chu thinks of transness not as the ‘expression,’ of an innate identity (the underlying stream of thought in the ‘born-this-way,’ narrative) but rather as an aesthetic choice that is driven by the desire for what one does not have.

Solanas’ pointed declaration that the XY chromosome is merely an anomaly and that the male is only an incomplete version of the female has been largely protested for the strictly biological idea it propagates. Chu reasons, however, that if the figure of the female is equated to completeness or wholeness then it is what becomes the ultimate desire. In this turnabout interpretation, all men want to be women and therefore, all men are trans women.

To clarify, Andrea Long Chu thinks of transness not as the ‘expression,’ of an innate identity (the underlying stream of thought in the ‘born-this-way,’ narrative) but rather as an aesthetic choice that is driven by the desire for what one does not have.

But if the SCUM Manifesto as the mother of radical feminism does indeed advocate for transness, then how does all of radical feminism come to be constituted as political lesbianism, an ideology that condemns heterosexuality as a whole for being an inherently patriarchal institution?

Taxonomy is taxidermy

Thus arises the problem with historiographies, says Andrea Long Chu. The disagreement over Solanas’ text to Chu is indicative of a more significant, intellectual habit within feminism, or rather, any ‘ism,’ itself. In a messy (which you will quickly come to see as a compliment) historiography of her own, Chu takes the reader back and forth in time to explore the inconsistencies rife in what has been so easily clubbed under the single heading of radical feminism in the Sixties and the Seventies.

She comes to the rather startling conclusion that radical feminism was at best, a “mixed bag,” that could not be generalised as trans-exclusionary in its entirety.

For those who say that trans women are merely men trying to crash ‘female-only,’ spaces by pretending to be women, Chu responds with a facetious retort citing imitation to be the highest form of flattery. With so many contradictions within these trans-exclusionary politics, how can political lesbianism come to stand in for the entirety of radical feminism as a movement?

Even within the ideas of political lesbianism, trans women according to Andrea Long Chu are nothing but its poster children. In turning the existing population of men into women, transness (Chu only half-jokingly adds) diminishes the current reserve of men on the planet, which should only support the larger project of political lesbianism.

For those who say that trans women are merely men trying to crash ‘female-only,’ spaces by pretending to be women, Chu responds with a facetious retort citing imitation to be the highest form of flattery. With so many contradictions within these trans-exclusionary politics, how can political lesbianism come to stand in for the entirety of radical feminism as a movement?

Political lesbianism then was only a part of radical feminism and not its ‘practice,’ as some self-declared radical feminists claimed. However, Chu deconstructs how the modern-day phenomenon of TERFs, though bearing a closer connection with trolling, borrows from notions of political lesbianism only in their collective dread of ‘desire’s ungovernability,’ says Chu.

Desire is de-political

This is to say that an individual experiencing desires that flow against the politics they associate with will almost always project these desires onto the other. This other, then, becomes the subject of marginalisation at the hands of the former.

In doing so, the former will try and ‘police,’ the desires of the latter, which at this point we know to extend to both sexual orientation and gender. Asking desire to conform to a political principle will never work because the very nature of desire is to transgress.

Politics must play a role in desire only to offer solidarity in the way that queers organise to demand equal rights, but politicising desire in its universalising tendency would imply that we begin to condone some and condemn others.

It is unpopular, Andrea Long Chu claims, on the left today to think about transition as a force of desire, rather than as expressing an inherent identity. Gender as identity and identity as a political concept present a need to bracket away the role of desire within gender. The less transition has to do with getting something, the more palatable it becomes to the rest of the closeted transphobic majority. The impetus to transition, in this case for a trans woman, comes from the desire to be a woman.

Gender is an aesthetic choice inasmuch as transition is the lovechild of transgressive desire. But these aesthetic choices are in no way personal, argues Chu. Gender by its nature is social, just as all aesthetic judgments are paradoxically subjective as well as universal.

Chu gives the example of what she calls “bottom surgery,” saying that most trans women want what popular queer discourse calls ‘sex-confirmation surgery,’ because “most women have vaginas.”

Politics must play a role in desire only to offer solidarity in the way that queers organise to demand equal rights, but politicising desire in its universalising tendency would imply that we begin to condone some and condemn others.

To transition, therefore, is to exist in a constant state of chasing your desire, because of the simple syntactic argument that once you have something, it is no longer a desire. This is what Andrea Long Chu calls the romance of disappointment. Desire implies deficiency, it implies want, which in turn implies a lack or a gap that must be endeavoured to fill.

‘Not getting something has very little to do with wanting it,’ says Chu, enigmatic and yet prophetic as always. The less attainable something is, the more you end up wanting it. In this sense, transness becomes an inherent state of motion, a constant anxiety to pass, a desire so deep it turns into dysphoria.

All references and quotations are taken directly from Chu’s piece originally published in n+1 magazine.

About the author(s)

Ananya is a writer and researcher of all things literature. With a particular emphasis on film, gender, and sexuality, she is great at curating the perfect movie night, but when it comes to life itself, she's still figuring out the script.

Such an interesting and completely immersive read Ananya. Great great piece!

amazing article 👏 great piece