Nipples. Check. Ass shot. Check. Masturbation. Check. Drugs. Check. Crotch shot. Check. This is the essence of Sam Levinson’s The Idol. Even though just three episodes of the series have been released thus far, it is clear that the show prioritises the ‘male gaze’. Although it was initially helmed by a female director Amy Siemetz, she had to exit the show because one of the co-creators Weeknd aka Abel Tesfaye “felt the show was leaning too much into female perspective”. With Sam Levinson onboard, the fetishistic scopophilia in the show has turned it into torture porn from a musical drama.

The red flags are shown early on in the show when Lily-Rose Depp’s character Jocelyn argues with the intimacy coordinator regarding her right to show her body off and subsequently is locked in the bathroom by her manager. The intimacy coordinator who is present to ensure her safety and well-being is shown as merely a nuisance. In another scene, Jocelyn’s friend Leia tells her that the Weeknd’s character Tedros gives off a rapey vibe, to which Jocelyn replies that she likes that about him.

The show has many such instances, where one would wonder if this is an honest portrayal of a troubled Pop Star or if the show is just treating its heroine as just another vessel carrying suffering and trauma.

The spectator enters this fantasy land through the eyes of the camera, operated by a man. Thus, despite any feminist literacy on the spectator’s part, the man’s eye presents the story. Just like the perspective is male-centric, the spectator is also assumed to be a man. Here, men are granted subjectivity, and the object being looked at is often a woman. However, the series is not the first nor will it be the last to engage in prioritising the male gaze.

The omnipresent male gaze

Simone de Beauvoir argued in her book The Second Sex that cinema, like religions, traditions, languages, tales, and songs, is a key carrier of contemporary cultural myths. And since the “representation of the world, like the world itself, is the work of men; they describe it from their own point of view, which they confuse with absolute truth“. Women lose their subjectivity by becoming an object to be looked at and written about. It leads back to the age-old debate about the dichotomy between the artist and the muse, the creator and the created. Yet, the dichotomy is still a relevant one, and shows like The Idol reminds us of that.

Feminists, across the board, have refused to treat cinema as an innocent medium meant for just entertainment. In Notes on Women’s Cinema, Claire Johnston considers film-like texts to be complex structures of linguistic and visual codes organized to produce specific meanings, and not just collections of images or stereotypes. Films, thus, can be seen, as carriers of ideology, wherein the notion of ‘woman’ acquires a patriarchal and sexist connotation. Irrespective of the overall messaging of these shows, the woman is a sign operating within the framework of sexist ideology that the show carries despite what it is pretending to actually represent.

The women in the context of such shows are shown to have the privilege of freely making their choices and they might even have the meatiest part in the movie, but they are nevertheless a sign that has to work within this fantasy land which is not meant to serve her.

Films, thus, can be seen, as carriers of ideology, wherein the notion of ‘woman’ acquires a patriarchal and sexist connotation. Irrespective of the overall messaging of these shows, the woman is a sign operating within the framework of sexist ideology that the show carries despite what it is pretending to actually represent. The women in the context of such shows are shown to have the privilege of freely making their choices and they might even have the meatiest part in the movie, but they are nevertheless a sign that has to work within this fantasy land which is not meant to serve her.

Having said that, The Idol can be seen as a piece of postfeminist media in the post-MeToo cultural milieu owing to the way it mocks and rejects the need for an intimacy coordinator. It hints toward the Postfeminists’ misplaced rejection of the ‘patronising’ and ‘puritanical’ attitude of Second Wave feminists toward sex and porn. Postfeminism was a backlash against the second wave’s alleged treatment of women as victims. It assumes that women have achieved equality by gaining equal access to the workplace. However, contrary to their claims, #MeToo exposes the vulnerability of women in those workplaces. The Idol, through various scenes, gives a nod to this idea by showing the complicity of the protagonist in her own sexual exploitation and abuse.

Studies hypothesise that cinematic apparatus affects spectators much like a dream. Though feminist scholars widely studied this dream-like effect of a large screen on the spectator, OTTs have stripped that surreal dream-like ambiance from cinema for the audience. However, if one closely looks at Levinson’s Euphoria and The Idol, and Netflix’s Blonde by Andrew Dominik, it does not take an expert’s eye to realise that the cinematography and ambiance in these visual narratives set out to have a dream-like effect on the spectator. The voyeurism and fetishisation of the female body are apparent in the way that it is treated, often fragmented, dehumanised, and hypersexualised. In early cinema, the male protagonist used to control the narrative while a passive female heroine who is reduced to an erotic spectacle usually danced and pranced around the hero. Nowadays, although OTTs have more female-oriented content, there is an element of reduced agency because of the invisible male hero behind the camera.

In The Queen’s Gambit by Scott Frank and Alan Scott, there is a long shot of Anya Taylor-Joy having a breakdown where she is drinking and dancing. The scene is long and uncomfortable to watch. Anya’s character is in a one-piece monokini and the camera runs across her body, often zooming in on her chest and crotch. Her put-together appearance is incongruent with her breakdown and she is represented in this way just to satiate the male gaze. Portraying women as sexy under all circumstances points to the unrealistic male fantasies and desires about women which is inherent to the cinematography.

The eroticised damsel in distress

Smita Patil, in one of her famous interviews, said that she does not want to work in women-oriented movies because rape and molestation are often used as plot devices for the woman to transform from a victim to a heroine. Patil understands the nuances of subjectivity and representation when acting in front of a camera operated by a man. Passivity is inevitable.

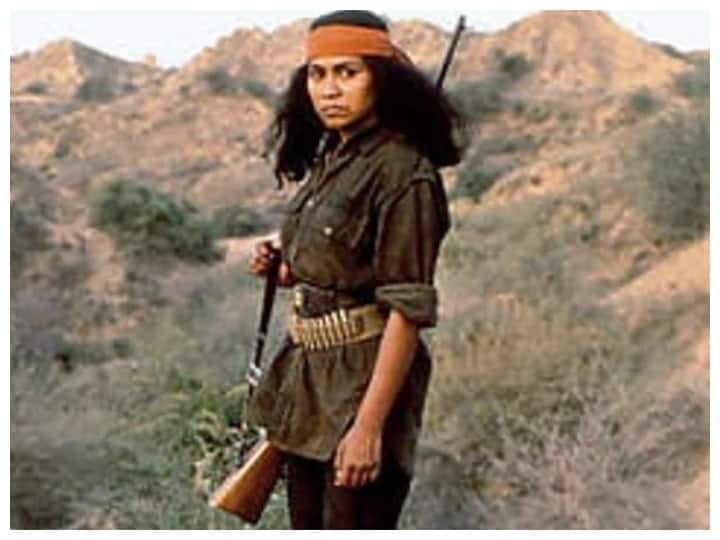

The most poignant example of this is the critically acclaimed movie Bandit Queen by Shekhar Kapoor. Arundhati Roy, in her essay “The Great Indian Rape Trick”, critiqued the movie for its objectionable portrayal of the protagonist Phoolan Devi. Roy rightly questioned the way this “female” oriented movie took away Phoolan Devi’s agency and reduced her life to a reductionist narrative of a wronged woman taking revenge on her wrong-doers. Rather than educating viewers about her trials and tribulations, the uncomfortably long rape scene served the purpose of titillating and giving sadomasochistic pleasure to a male audience.

Similarly, Netflix’s Blonde had little interest in shedding light on Marylin Monroe’s life. Instead, it exploited certain salacious and sketchy details from her life in order to titillate a male audience. Monroe’s humanity and autonomy are reduced by her representation as a ‘damsel in distress’ with daddy issues. Her entire life and relationships are defined by her relationship with her dead father. In early cinema, female characters with daddy issues were usually portrayed as ‘sluts’, who are the butt of jokes and mockery by male characters. Nowadays, this archetype of woman is not only considered to be morally loose but also an object of pity and fetish. Her life narrative is reduced to a caveat. She not only feeds the masculinist fantasies about submissive and vulnerable women who need rescuing but also serves as a lesson to other women, warning them that their inherently sexual nature will be punished in the end.

The female gaze

Blue is the Warmest Color by Abdellatif Kechiche was criticised for its exploitative and hypersexualised gaze on women’s bodies and their lesbian relationships. On the other hand, Park Chan-Wook’s The Handmaiden which was praised for its triumphant story about two lesbian women, still strives to satisfy the male gaze throughout the movie culminating into a highly voyeuristic sex scene between the two protagonists.

Although these movies had lesbian protagonists, they were not exactly made for them. The nudity in these movies was celebrated as liberating but it was gratuitous at best and voyeuristic at worst. While comparing the aforementioned films to the sexual and violent content in shows like I May Destroy You by Michaela Coel or the movie Promising Young Woman by Emerald Fennell, it is clear how starkly the female gaze differs from the male gaze.

In I May Destroy You, the camera chooses to focus on the rapist rather than showing the victim while she was struggling. In Promising Young Woman, the rape scene is never shown. These media carried their ideology as well. However, their ideology refused to serve the purpose of the patriarchal structure or cater to the male gaze. They portrayed their heroines as humans whose trauma was not meant for the audience to voyeuristically engage with. Instead, the depiction of their traumatic experiences aimed to elicit a cathartic response from spectators.

In I May Destroy You, the camera chooses to focus on the rapist rather than showing the victim while she was struggling. In Promising Young Woman, the rape scene is never shown. These media carried their ideology as well. However, their ideology refused to serve the purpose of the patriarchal structure or cater to the male gaze. They portrayed their heroines as humans whose trauma was not meant for the audience to voyeuristically engage with. Instead, the depiction of their traumatic experiences aimed to elicit a cathartic response from spectators.

The deeply empathetic view with which the camera gazed at the women generates relatability rather than detachment. Although this is not to say that female creators do not produce voyeuristic sexual content, it is imperative to acknowledge that there is an increasing need for creating an alternative language of desire in order to liberate the spectator from their sexual identity by making content that sees women as flesh and blood humans.

Hey Rishija! Aena here from Pakistan. I was casually scrolling through this amazing FII’s website when I came across your article. The title instantly grabbed my attention because it’s a subject I’m deeply interested in and care about.

Even though I have a short attention span (thanks, social media!), I still decided to read your article, and oh my goodness, it’s such a powerful and well-written piece! I wanted to write about this topic myself, but honestly, you nailed it way better than I could ever have.

Btw, I’m currently reading Simon de Beaviour’s “The Second Sex” and “Young Promising Woman” is also one of my favorite films for all the reasons you highlighted. In short, the article totally resonated with me, and I absolutely love you for writing it! Keep up the fantastic work!

Hey Aena! Thank you so much for your appreciation. I am glad that you read the entire piece. And, yes! please do watch Promising Young women, its a fantastic movie.

Hey Aena! Thank you so much for appreciating the article. I am glad you read the entire piece. 🙂