Ahead of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, debates on the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) have resurfaced. The issue caught the nation’s attention after Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a pitch about the same in Bhopal on June 27, 2023. PM Modi’s statement was preceded by a notice issued by the 22nd Law Commission of India, seeking the opinions of the concerned stakeholders on the Uniform Civil Code. It is important to note here that prior to this, the 21st Law Commission of India had examined the subject of UCC and solicited the views of all the stakeholders through a questionnaire.

The overwhelming response it received yielded the conclusion that the counter-consequences of a uniform civil code are vast and virtually untested in India. Thus, the commission issued a ‘Consultation Paper on Reform of Family Law’ on 31 August 2018, with the aim of preserving the ‘diversity and plurality that constitute the cultural and social fabric of the nation‘.

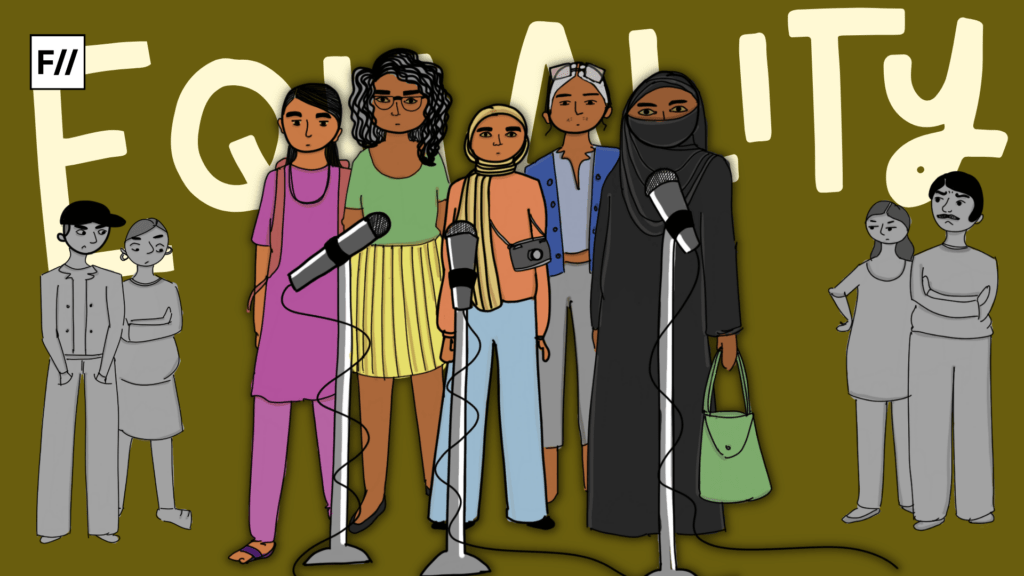

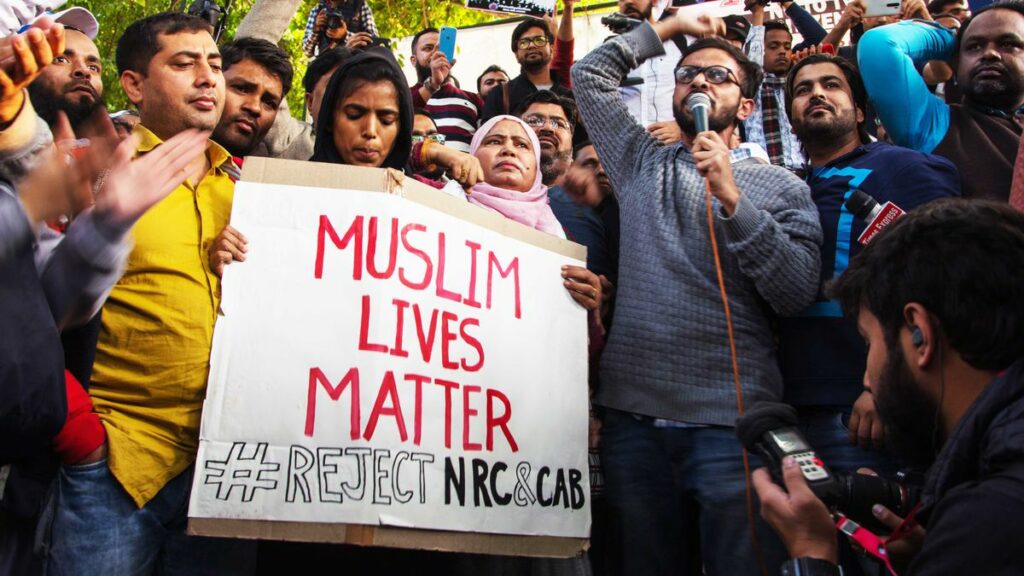

Muslim women have emerged as significant stakeholders in this debate as gender equality and national integration are flagged as one of the prime motives of the Uniform Civil Code. However, it is important to emphasise here that there are several other stakeholders in this discourse, as opposed to the popular representation of UCC as a ‘minority issue’, which inadvertently translates to a ‘Muslim issue’, often erasing the resistance coming from tribal communities, other minorities and certain Hindu sects as well.

Muslim women have emerged as significant stakeholders in this debate as gender equality and national integration are flagged as one of the prime motives of the Uniform Civil Code. However, it is important to emphasise here that there are several other stakeholders in this discourse, as opposed to the popular representation of UCC as a ‘minority issue’, which inadvertently translates to a ‘Muslim issue’, often erasing the resistance coming from tribal communities, other minorities and certain Hindu sects as well.

UCC: A feminist issue?

The question of Indian Muslim women is important in the larger political climate of the nation. The UCC emerged as a decisive debate after it was deployed as a political tool by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the wake of the Ayodhya conflict, the dramatic growth of the BJP and its tirade against the Congress government’s alleged tactic of ‘Muslim appeasement.’

Muslim women have been featured as major pawns in this majority/minority politics, with their oppression being traced back to Islamic law along with the continued emphasis on a gender-just civil code. However, as Zoya Hasan remarks in Religion, Feminist Politics and Muslim Women’s Rights in India, the UCC was rarely articulated in the public consciousness as a feminist issue, despite gender equality being one of its anchors. Instead, it became a debate about uniformity versus minority rights, secularism versus religious laws and modernisation versus tradition.

The very futility of a uniform civil code proves its sustained use as simply a tool for political mobilisation. The 21st Law Commission of India itself remarked in its working paper that a UCC is ‘neither necessary nor desirable at this stage‘. In its 185-page Consultation Paper, the Commission went on to suggest some very progressive reforms in personal laws of various communities with regard to inheritance, adoption and the economic rights of women.

The very futility of a uniform civil code proves its sustained use as simply a tool for political mobilisation. The 21st Law Commission of India itself remarked in its working paper that a UCC is ‘neither necessary nor desirable at this stage‘. In its 185-page Consultation Paper, the Commission went on to suggest some very progressive reforms in personal laws of various communities with regard to inheritance, adoption and the economic rights of women. However, 4 years later, they have remained as mere suggestions. Now, the 22nd Law Commission has rekindled the issue.

Furthermore, detractors of UCC argue that India already has certain levels of a common civil code for contentious issues like domestic violence, divorce, maintenance and inheritance etc. In such a case, the flaw does not lie with a uniform civil code, but its ideological deployment instead. The focus is heavier on ‘uniformity’ than ‘equality’. Tahir Mahmood, an expert in personal laws, highlights that the ultimate objective of Article 44 is secularity in family law, ‘the call for uniformity is merely the means‘.

Double jeopardy: A conservative clergy, a complicit state

Furthermore, in the context of the dilemmas that Muslim women face, foremost is the increasing protectionist approach towards Muslim Personal Laws by the clergy, resulting in a group identity being assimilated around the conservative idea of Islam. As Vrinda Narain argues in Gender and Community: Muslim Women’s Rights in India, “The convergence of personal law and religious identity and the conceptualization of women as markers of the cultural community have profound implications for the position of Muslim women.” It leads to Muslim women being deemed as the bearers of Islam. In this case, anything directed towards them inadvertently becomes a threat to Islam, completely overshadowing their added burden of also being a woman.

On the other hand, the state, although claiming to work towards gender equality, works in collaboration with this conservative clergy whose interpretation of Islam continues to be masculine in its approach. As Narain argues, “The state’s uncritical acceptance of fundamentalists as the sole representatives of Muslim interests has resulted in the continued subordination of Muslim women.” This is supported by the sheer lack of Muslim women in the Indian parliament, with them comprising only 4 of the 543 members in the outgoing Lok Sabha.

Another example is the Sachar Committee Report of 2006 having virtually no female member on board. Furthermore, as Maidul Islam notes in Indian Muslims After Liberalisation, the issues of Muslim women have been discussed in the Sachar Committee Report in very small subsections as in ‘Identity and Gender’. In such a situation, Muslim women continue to be spoken for and reduced to vignettes, often becoming puppets at the hands of people with their own vested interests.

The current ambiguous power-sharing arrangement between the state and the ulema also greatly disserves Muslim women. Although several secular laws have been passed to allay the biases in Muslim personal laws, their impact is scarce because they remain detached from the ground reality.

While Narain argues for the implementation of a gender-just UCC, it must be noted that in the context of communalised polity, the implementation of a UCC can have severe counter-consequences with regard to the fundamental rights of religious minorities. However, the current ambiguous power-sharing arrangement between the state and the ulema also greatly disserves Muslim women. Although several secular laws have been passed to allay the biases in Muslim personal laws, their impact is scarce because they remain detached from the ground reality.

Citizenship in practice: Socio-economic positionality and legal literacy

Considering the few official surveys and micro-studies done on the socioeconomic status of Muslims, such as that done by the Sachar Committee, the Gopal Singh Committee and the National Commission for Minorities, it is proven that socioeconomically, Muslims are one of the most backward groups in India with little to no political representation. Maidul Islam argues that the “Indian state has included Dalits, Adivasis, and OBCs within the purview of affirmative action and reservation policies with a protective legal framework. However, it has shown very little interest to do the same in the case of religious minorities.”

The situation of Muslim women is even more dire. There is no official enumeration of the socio-economic standing of Muslim women in India. However works of scholars like Zoya Hasan and Ritu Menon, such as Unequal Citizens: A Study of Muslim Women in India and Educating Muslim Girls: A Comparison of Five Indian Cities continue to explore this area. Another work that studies socio-economic and demographic aspects of Muslim women in Bengal is Rural Muslim Women: Role and Status by Sekh Rahim Mondal.

The premise of these works is that the socioeconomic positionality of Muslim women vastly determines the extent to which everyday Muslim women can engage with law and religious ideology. Thus, in the absence of discourse around affirmative policies, a gender-just UCC would remain a static document as so many ‘reports’ and ‘consultation papers’ have.

The state needs to engage with Muslim women activists and NGOs working on the ground, in order to be in touch with ground reality. Several groups such as Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan (BMMA) and All Indian Muslim Women’s Personal Law Board (AIMWPLB) are making a call for reform within personal laws. BMMA has proposed a revised draft of the Muslim Family Law which disavows and abolishes the biases in the personal law.

Furthermore, the state needs to engage with Muslim women activists and NGOs working on the ground, in order to be in touch with ground reality. Several groups such as Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan (BMMA) and All Indian Muslim Women’s Personal Law Board (AIMWPLB) are making a call for reform within personal laws. BMMA has proposed a revised draft of the Muslim Family Law which disavows and abolishes the biases in the personal law.

It broadly concerns itself with polygamy, nikah halala, muta marriages, inheritance and property rights of wives and daughters advocating for Talaq-e-Ahsan (rightful divorce) as the legal method of divorce where arbitration is necessary. The BMMA also calls for a codification of Muslim personal law. While it deems that codification alone would not solve everything, it certainly lessens the ambiguity that surrounds Islamic jurisprudence.

A case in point is; In 2012, Nida (name changed), a 35-year-old Muslim woman residing in the village Karaundi, district Ayodhya, was arbitrarily divorced by her husband in the absence of witnesses by Talaq-e-Bid’ah or Triple Talaq. Her husband refused to give her the mehr amount or return the dowry. After being sensitised by a local law graduate, Nida filed a case in a family court and received 3 Lakhs from her husband as compensation. The matter was settled by mutual consent.

However, in a conversation with her, I discovered that she is unaware of the fact that her husband is bound by law to provide a ‘sufficient sum’ as her maintenance for her entire life. Many other Muslim women like her are unaware of their most basic rights with regard to maintenance, property and divorce etc.

What must also be highlighted is this “imagined consent”; since these are the same women who are unable to negotiate the terms of their nikahnamas and are not oblivious to their most basic rights. Moreover, the parties involved in the process of arbitration are mostly men, and the ambiguity of the process allows for conservative minds to dictate the terms of the dispute. The legal realities of Muslim women are discussed in great detail in Mengia Hong Tschalaer’s Muslim Women’s Quest for Justice.

Furthermore, many Muslim men have found other ways to avoid legal charges. For instance, the cases of desertion are increasing after the Triple Talaq Law. A study by Shaheen Women’s Resource and Welfare Association (SWRWA or Shaheen) in Hyderabad found that out of 2,106 households surveyed, 683 had women who had been deserted by their husbands.

In such a scenario, laws may be passed, but if a certain section of the population is not empowered enough to make use of these provisions, then it is an exercise in futility. In this regard, BMMA is making significant changes with its female qazis and female shariah courts as well as the establishment of Darul Uloom Niswan, a women’s qazi training institute. Laws must be grounded in reality, they cannot be assessed simply by their wordings, but by their application to real-life situations. As Flavia Agnes notes, it is most well put in the legal maxim, law is what law does.

Note: Nida’s original name is changed for privacy reasons. The interview was conducted by Tasneem Khan in July 2023.

Good English with a mix of not leaving islamic radicalism at any cost