We would be hard-pressed to find an Indian who hasn’t dealt with fake news- from the pseudoscientific junk so dedicatedly forwarded by our benevolent uncles and aunts on every family group to our own spaces on social media, where fraudulent news and sensational headlines are peddled at a frightening pace to stir hate. But while an increasingly digital-savvy Indian crowd finds itself reckoning with fake news and other such problems that the recent digital transformation has wrought on us, it’s undeniable that victims of such fake news remain isolated to some of the country’s most vulnerable marginalised people.

Digital literacy becomes a feminist issue, and the need for digital literacy has especially been intercepted by the Digital Empowerment Foundation, an organisation dedicated to arming citizens with the tools necessary to “make informed judgements as users of information and media, as well as to become skilful creators and producers of information and media messages in their own right.”

As such, digital literacy becomes a feminist issue, and the need for digital literacy has especially been intercepted by the Digital Empowerment Foundation, an organisation dedicated to arming citizens with the tools necessary to “make informed judgements as users of information and media, as well as to become skilful creators and producers of information and media messages in their own right.”

The need for digital literacy

It becomes crucial to analyse the severity of fake news in India. In 2019, a survey conducted by Microsoft for the third edition of its ‘Digital Civility Index’ revealed over 60% of Indians had seen fake news online against the global average of 57%. More recently, in April, tech giant Google declared a slew of measures to combat online misinformation campaigns, including prioritising information and news obtained only from official or recognised sources and training users to spot misinformation and report the same effectively.

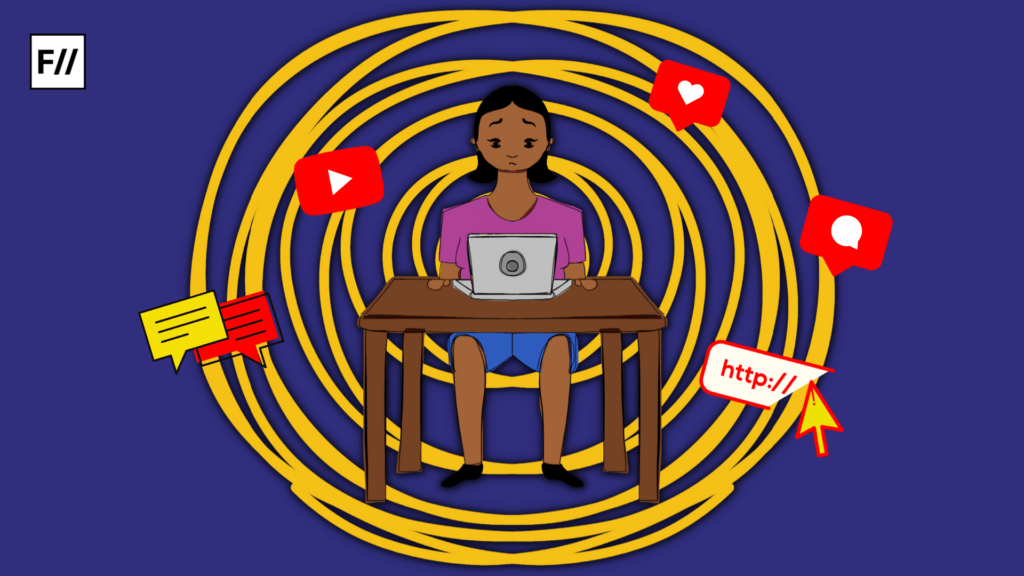

However, data on fake news remains cold; it is only when the real-world implications of fake news are truly acknowledged that the horror of the situation becomes more apparent. For instance, social media has recently witnessed the brutal, terrifying trial held against Amber Heard by her ex-husband and popular Hollywood actor Johnny Depp for alleged defamation. While the trial itself was a long-winded affair, social media users launched one of the most misogynistic misinformation campaigns against Heard, the consensus amongst several insular Internet communities- Incels, MRAs and such- was that she deserved to be hounded for not being the “ideal victim.”

With distorted clips and downright false information being peddled on platforms such as Twitter and Tiktok, the trial was reduced to sensational, divisive headlines that could fuel misogynistic harassment. Several users pontificated on how easy it was to essentially lull huge amounts of people into participating in a massive harassment campaign only by stoking their misogynistic beliefs through social media.

This isn’t the only example of social media being used as an extremist tool to evoke violence. A poll conducted by the charity organisation Hope, Not Hate, found that 8 in 10 boys in the United Kingdom, aged between 16 and 17, had watched content from Andrew Tate, detained on charges of sex trafficking and rape. 45% of men between the ages of 16 and 24 held a positive view of Tate. Only recently did Youtube, Google, and such media giants clamp down on Tate’s content, indicating that the companies were aware of the power they held in aiding the spread of Tate’s violently misogynistic content.

The nature of communal hatred peddled in cyberspace is also invariably gendered. Only last year did the case of such apps like ‘Sulli Deals’ send shockwaves through India, forcing its people to come to terms with the very real and material consequences online trolling and cyber-bullying can have when left uninhabited.

By commodifying marginalised women, and encroaching on their bodily autonomy, perpetrators of the crime laid bare the grim reality of “digital India”- in much the same way as men limited women’s physical spaces and movement, so too did men make online spaces an unsafe place for women. It is no surprise that a report by the NYU Stern Centre found that “a spate of misogynistic rants by nationalistic Indian YouTube influencers have made such [violent and sexist] invective popular on the platform.”

Clearly, the need to identify misinformation is a feminist issue. Fake news, cyberbullying, trolling and hate speech disproportionately affect women, Muslims, queer people and other marginalised communities in India.

The right to a safe online space free from harassment and abuse is an inviolable right in today’s increasingly digitised world, yet experiences recounted by women, especially those who are further marginalised by religion, caste, or sexuality, only indicate how little attention has been given to making online spaces truly safe by both legislators and social media platforms themselves.

Incendiary rumours spread by Indians on social media have been linked to the tensions between the Hindu-Muslim communities in Leicester. Only a few weeks ago, India witnessed a tragic train crash; this disaster was effectively harnessed by trolls and Islamophobes to fan rumours about an alleged mosque near the site of the crash in an effort to perhaps disparage the Muslim community and invite people to spread baseless junk and ignite fresh rounds of hate against them (the religious shrine was later found to be a temple.) In a study conducted by BOOM, a fact-check agency, it was found that Muslims constituted the most vulnerable demographic for fake news- nearly 14% of fact-checks conducted by BOOM were news found to be false or distorted to stoke hate against them.

Clearly, the need to identify misinformation is a feminist issue. Fake news, cyberbullying, trolling and hate speech disproportionately affect women, Muslims, queer people and other marginalised communities in India. Against such a backdrop, it becomes necessary to equip an increasingly tech-savvy Indian crowd with the tools to navigate online spaces freely and safely.

Media illiteracy and fake news: DEF’s mission

With its motto ‘Inform, Communicate, and Empower,’ DEF was envisioned as an organisation meant to help bring to light the digital divide amongst marginalised communities in the country. Over time, the DEF has expanded its mission to multiple states; it has created an extensive campaign that involves addressing hate speech on the internet, campaigning for the right to access digital infrastructure, educating people on how to fight against trolls, scammers, phishers and other cyber-criminals, and, staying true to its name, digitally empowering local communities through on-ground organisational work.

Amongst some of its most notable projects include efforts to financially empower rural women and ensure a modicum of financial security for them, helping envision new, radical modes of education through self-directed learning, and even sponsoring fellowships for those dedicated to the cause of digital empowerment. The foundation further provides the space to hold enlightening dialogue on myriad issues concerning internet freedom and digital accessibility and workshops such as one held in Maharashtra for media professionals on democratising data protection.

In 2014, DEF further initiated a project titled IMPACT to invite the participation of civil society advocates and activists to enlist their help in aiding people with the knowledge to address digital crimes or violations. Under its Women Act Against Trolls project, DEF helped construct a community to fight against trolls and stalkers.

In a novel program organised by DEF, women in rural and tribal communities are provided digital education through its Community Information Resource Centers (CIRCs.) In collaboration with IBM (The International Business Machines Corporation), DEF particularly helped impart coding and other important skills for the holistic development of girls in rural areas. An intricate network of such resource centres has been established throughout the country to help aid DEF’s mission and realise its goals.

In 2014, DEF further initiated a project titled IMPACT to invite the participation of civil society advocates and activists to enlist their help in aiding people with the knowledge to address digital crimes or violations. Under its Women Act Against Trolls project, DEF helped construct a community to fight against trolls and stalkers.

A concerning number of women have been subjected to harassment from men online, and DEF’s project provides women with information kits and handy resources to deal with the same. Indeed, DEF’s mission has been realised through a multitude of projects, each of which is enacted passionately by its members, united in the cause to fight for digital freedom and safety. A booklet guiding users on navigating online harassment and cyber crimes is also available online. A comprehensive list of projects and initiatives of the foundation can be viewed on its site.

Combating fake news: The way forward

Social media has emerged in recent times as an incredibly potent tool. On the one hand, it is a means for people to organise and reach out for help. On the other hand, the online sphere is a space riddled with horrors, and navigating the same with almost no discomfort or fear is only an extension of one’s privileges. India has reached a particularly frightening stage in its politics- unbridled online hate campaigns have very real, material impacts. They kill people. They silence entire groups into oblivion.

Digital spaces are echo chambers wherein oppressors configure new strategies to further marginalise women, religious minorities and sexual and gender minorities to erase their voices.

At such a crucial juncture, it becomes important to organise and reach out to one another. DEF’s goal to empower those who have been long excluded from conversations surrounding digital infrastructure is one important step in providing people with the tools necessary to fight. In building a huge community of digitally-aware citizens, DEF has served to solidify solidarity amongst people, to help unite them and assist each other in the face of increasingly extremist online bigots.

At such a crucial juncture, it becomes important to organise and reach out to one another. DEF’s goal to empower those who have been long excluded from conversations surrounding digital infrastructure is one important step in providing people with the tools necessary to fight. In building a huge community of digitally-aware citizens, DEF has served to solidify solidarity amongst people, to help unite them and assist each other in the face of increasingly extremist online bigots.

By creating a strong support network and implementing a variety of projects that address the needs of women in the new digital landscape, DEF has cemented its place as an ally in the fight for freedom. One can only expand DEF’s vision by becoming more digitally aware. That one misinformed post sent by your distant relative on the Whatsapp group? You can start by calling it out.

This article is part of the A-code partnership between FII and DEF. DEF is active on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, LinkedIn, Instagram and you can check their website for more details.

About the author(s)

Mayank (he/him) is an 18-year-old student hailing from Delhi. He is particularly interested in offering cultural and literary critique through the lens of feminist and queer studies. In his free time, Mayank enjoys reading theory and is known to appreciate pictures of pet cats.