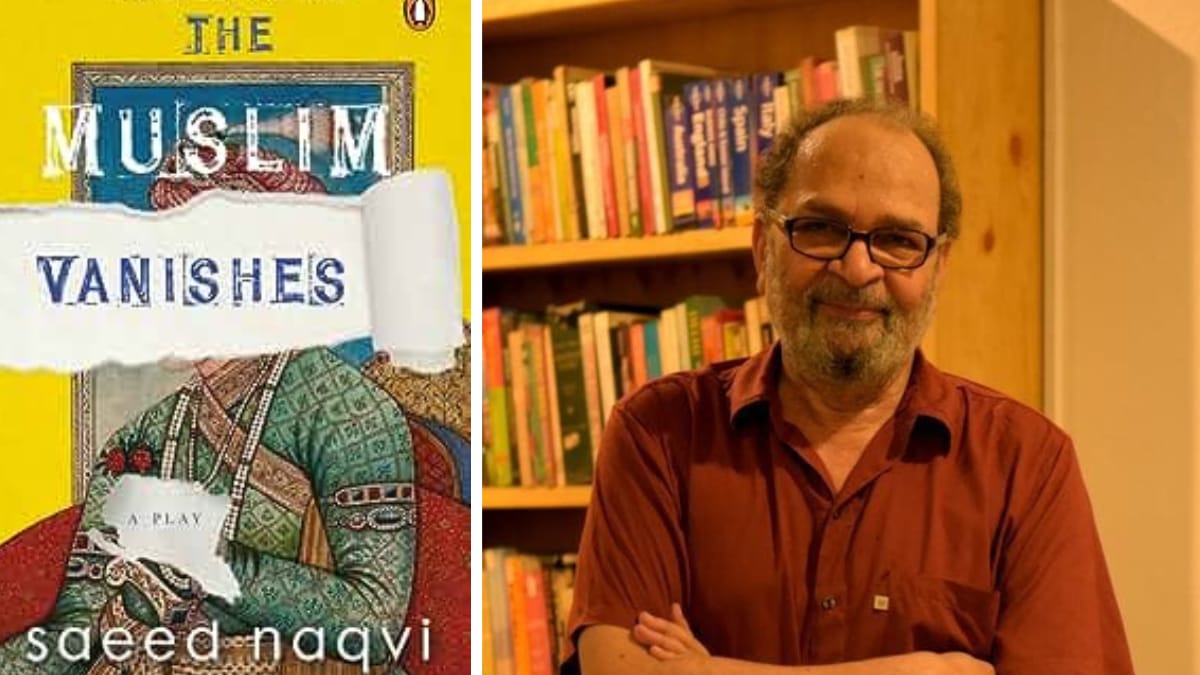

Caught up in a society that is so quick to demonise and vilify, the play The Muslim Vanishes by Saeed Naqvi is a touching piece on how to persist alongside fear, a brilliant work of literature that truly captures the fears of a community under attack. Saeed Naqvi begins by asking the question ‘What could or would happen if the Muslim community of India vanishes?‘ To answer this question the Muslim community vanishes at the beginning of the book.

The relevance of The Muslim Vanishes in India today

The Muslim Vanishes tells a story that is very relevant in India in today’s time, when hate has been let loose and we are at the beginning of the genocide of a community of two hundred million Muslims who face all sorts of violence including the hijab ban, the constant lynchings, hate speeches against them, corona jihad, love jihad, halal meat ban, the demolition of their livelihoods and homes and the demands for restrictions against the azaan and namaz in public spaces.

Saeed Naqvi reminds us with this play that genocide is a terrible violent process that takes decades to lead to a holocaust but once it does there is no stopping it. He reminds us to pay attention to the signs, to not look away, and to not make excuses.

It is a book that comes at a time when the world needs a reminder to be empathetic, be responsible for their actions, and never forget their history. Saeed Naqvi reminds us with this play that genocide is a terrible violent process that takes decades to lead to a holocaust but once it does there is no stopping it. He reminds us to pay attention to the signs, to not look away, and to not make excuses. As Amir Khusro says ‘Zehaal-e miskin makun taghaful, Duraye naina banaye batiyaan‘ (Do not ignore my misery, by looking away and making excuses).

What happens when the Muslim vanishes?

The play begins with the normal life of a country, but things seem strange in the newsrooms. Befuddled news reporters are trying to make sense of something very bizarre which is beyond anything they could ever imagine- the Muslims of India have vanished, taking with them cultural inheritances such as- songs, language and food (No more Biryani!). They have even taken the Qutub Minar away and have also dug up the graves and taken away their dead. When reporters begin searching they find out that the Muslims seem to have shifted to Kashmir which complicates the matter further.

At the beginning of the play the characters begin to debate amongst themselves- what else can the Muslims take back? Can they take back the ghazals? Can they take back words that have been taken and appropriated from Urdu? What happens to the biryani, kebabs, and nihari? Will paintings vanish? But before they can worry too much they seem to realise that the Muslims have left behind their houses, their wealth, their lands, farms, animals and cowsheds and they begin to imagine how they must divide this newfound wealth.

Reformulating the anxieties of hatred and oppression

But before they have a chance to take hold of the land, the Dalit community, the OBC’s and the lower castes have already taken over the lands left behind and the savarnas begin to understand the gravitas of this bizarre situation, As one of the anchors remarks, ‘200 million have left behind their homes, farms, land, businesses, cowsheds, buffalo sheds… All of this wealth will be the dividend… that we must divide among ourselves. It remains to be seen who gets what.‘ This gives rise to apprehensions that the ‘lower castes’, which are entitled to certain benefits, may well begin to set their eyes upon the ‘Muslim wealth left behind‘.

Slowly the upper caste Hindus begin to realise that without the Muslims their community breaks up on the basis of caste where the lower castes are the majority, not the upper castes. The upper castes have no way to unify them in a hierarchical structure because as one of the characters says poignantly in the play ‘now that Muslims have disappeared there is no one left to hate.‘ The battle lines have been redrawn and there has been a shift in the electoral pyramid as well. The upper caste Hindus shrink back as realisation dawns on them that without the Muslims the Dalits are the majority in electoral booths. This means their candidates will win, making the possibility of a Dalit prime minister more real now than it ever has been before.

The crafty upper caste Hindus then rush to find a way to stall the elections so that they can find a way to bring back the vanished Muslims. A Brahmin politician’s son who is also a prime time reporter states ‘Today, without the Muslims, the battle lines have been redrawn. It is Savarnas versus Avarnas, upper castes versus lower castes.‘

The Muslims are the same community that they vilified and brutalised. But there is a realisation among the upper castes that without the Muslim community in India to act as scapegoats for their hate, they will lose to the majority of OBC’s, Dalits, the lower castes and the Adivasis

There is a rush to find a way to get the Muslims back. The Savarnas’ disgust for the Dalits and OBC’s and their fear of having a Dalit Prime Minister compel them to try and find a way to bring the Muslims back. The Muslims are the same community that they vilified and brutalised. But there is a realisation among the upper castes that without the Muslim community in India to act as scapegoats for their hate, they will lose to the majority of OBC’s, Dalits, the lower castes and the Adivasis.

The crisis of a Hindu nation

The situation becomes so serious that a court is called with an eleven-member jury. With all its wit and imagination, this is where the brilliance of the play comes to life. On the recommendation of the Sufi saint Barabanki, Shah Abdul Razaq, the jury is chaired by Urdu poet and Constituent assembly member Maulana Hasrat Mohani. Best known as the author of the romantic ghazal ‘chupke chupke raat din aansu bahaana yaad hai’, he is a social activist and reformer who stood against untouchability and the caste system, and was a pioneer for women’s education in India, and a brilliant writer. Joining them in the jury are also the poets Rakshan, Salbeg, Abdul Rahim Khan-e-Khana, Mohsin Kakorvi, Chunnalal Dilgeer, Alladiya Khan, Kabir, Tulsi Das, an anonymous nominee of Guru Nanak, and Amir Khusro.

The jury chooses Amir Khusro as its spokesperson and a debate ensues in court, shifting back and forth between history and the present, touching upon hate news and propaganda against communities, and the death of democracy. There are solutions given to make India a place which no one would want to leave, Amir Khusro’s suggestions are- creative programming of TV and a change in journalism- one that is focussed not just on the market, but also examines the place of democracy, constitution, and tradition, to create a country that no one wants to leave.

But as a debate ensues in the courtroom, rampant casteism unfolds outside and inside. Casteism festers inside politicians and their politics while upper-caste Hindus outside try to call back the Muslims. The play ends with a suggestion which hints that the court does not matter anymore because the president has declared an indefinite emergency. Chaos erupts, and that is where Saeed Naqvi ends his beautifully imaginative play.

This play is relevant now, more than ever, as a call for peace and empathy, it rings a bell which awakens people, urging them to wake up, confront reality and change the course of life from hate to humanity and love. It is a must-read play for those who want empathy and also for those who have not yet understood the importance of a history that cannot be cherry-picked through and must be accepted as a whole including the good and the bad. It is a play that would be picked up again and again by readers when the world in reality becomes too much to bear.

About the author(s)

Zeba Vagh is pursuing her degree in screen writing from Whistling Woods Mumbai International. An aspiring writer, her work has been published with the Live Wire. She can be found on Instagram.

Very well written Zeba