Oppenheimer is a multi-genre film that tells quite a few stories. While primarily centred around the man behind the invention of the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Oppenheimer is also about the collective complicity of intellectuals, politicians, and the public in rationalising the creation of mass destructive nuclear weapons. It relates another story set around the Cold War that portrays the United State’s excessive surveillance and paranoia around communism (McCarthyism), of which Oppenheimer becomes a severe victim.

Oppenheimer is a period piece, a slightly-fictionalised biopic, and a psychological and political drama all rolled into one. It depicts unfair security hearings, senate hearings revolving around Lewis Strauss’s confirmation as the Secretary of Commerce, and a community of scientists variously engaged in lively intellectual discussions and strategisations, who are ignored by the government in terms of their political participation.

The film is based on a Pulitzer-winning biography, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, written by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin. Christopher Nolan is mostly faithful to the book and made very few alterations in terms of the plot. Oppenheimer is a period piece, a slightly-fictionalised biopic, and a psychological and political drama all rolled into one. It depicts unfair security hearings, senate hearings revolving around Lewis Strauss’s confirmation as the Secretary of Commerce, and a community of scientists variously engaged in lively intellectual discussions and strategisations, who are ignored by the government in terms of their political participation.

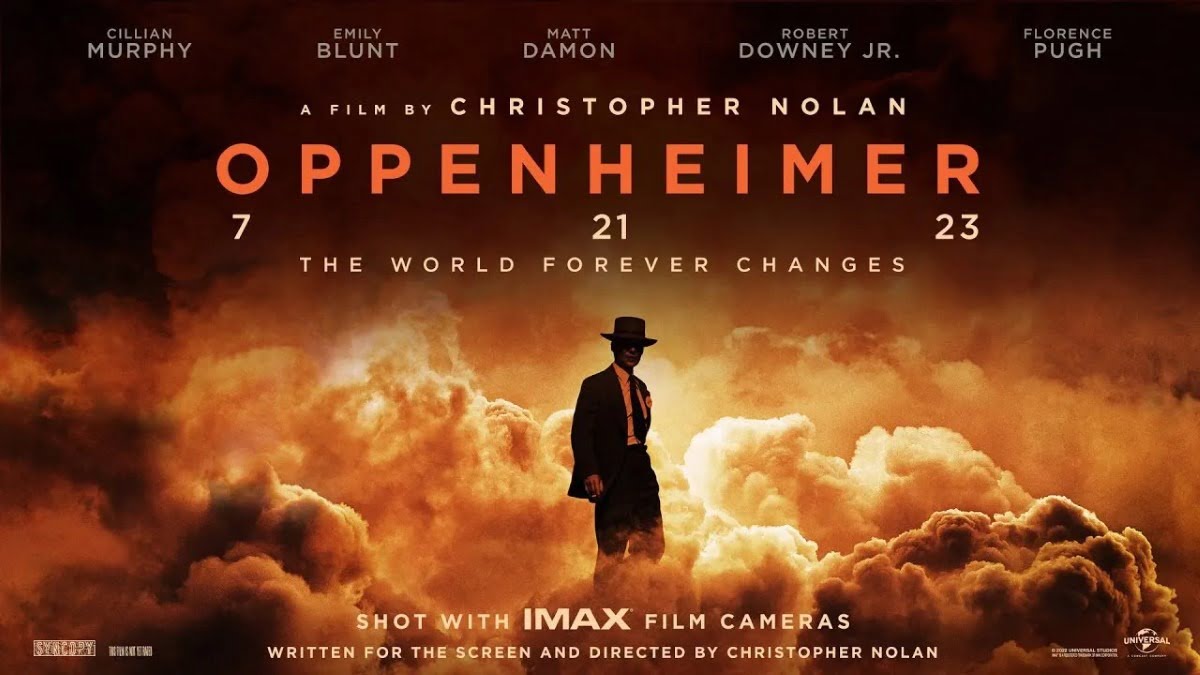

The first hour of the movie deals with the basics of Oppenheimer’s life. The second hour depicts his mission to create an atomic bomb, and the third hour portrays its unalterable consequences. Oppenheimer is played by Cillian Murphy whose gaunt face and haunting eyes dominate the screen communicating intense anxiety and a sense of doom.

Technical achievement, structure, and form

The film is brilliantly made and technically accomplished. The portrayal of Oppenheimer’s various psychological states are achieved through intensifying music and cinematography (we have the composer Ludwig Göransson and the cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema to thank for that). One such psychologically intense scene is when Oppenheimer delivers a speech to a roomful of people and his crushing sense of guilt and regret are sharply opposed to the words coming out of his mouth. His surroundings melt and the voices drown indicating his isolation from the spirit of the room. The source of the recurring foot-thumping sounds, which served to communicate a sense of foreboding in prior scenes, is revealed.

Apart from the brilliant visuals and music, the audio of the film was excruciatingly stifled. Nolan seems to have deliberately made this choice because dialogues in his previous works are equally muffled or inaudible. This can be extremely frustrating especially since Oppenheimer is a dialogue-heavy film which requires the audience to stay alert for three hours (the lack of subtitles did not help either). I missed so much of it that I only understood the film on my second viewing.

In terms of form, Oppenheimer is a film characterised by multiple timelines with no identifiable present. While the conventional narrative structure usually has a definite present that relates past events of possibly different timelines, there is no main, overarching time period in the movie. This gives a sense of contemporaneity to every timeline despite some having been identifiably taken place in the past.

The muted hues of coloured timelines in Oppenheimer’s perspective and the black and white of Lewis Strauss’s point of view are certainly puzzling but thinking about it can render why such a choice was made. What came through with this difference in the colour schemes? I, for one, thought that the coloured realm was very human in its telling; perhaps because Oppenheimer’s memories dealt with a vast range of emotions and relationships dealing with love, ambition, guilt, and anxiety. The methodical vindictiveness of Lewis Straws, which is all we know about him, is perhaps befitting for austere black-and-white frames.

The women in Oppenheimer

Katherine “Kitty” Oppenheimer, a biologist who, in her words, ‘graduated to housewife‘, is performed by Emily Blunt. She is terrific in her role as a pragmatic, shrewd woman who repeatedly pressurises Oppenheimer to ‘fight‘. She seems to be the only person with the power to tell him to deal with the consequences of his wrongdoings. After Oppenheimer’s first lover, the communist Jean Tatlock (played by Florence Pugh) who dies by suicide, which Oppenheimer blames himself for, Kitty berates him: ‘You don’t get to commit the sin and then seek sympathy from the rest of us.’

Kitty fights. She fights (like she wants Oppenheimer to) when Roger Robb (played by Jason Clarke) ambushes her during cross-examination at the security hearing. Despite her disappointingly little screen time, Blunt’s Kitty becomes a sturdy presence throughout Oppenheimer’s most difficult times.

Kitty fights. She fights (like she wants Oppenheimer to) when Roger Robb (played by Jason Clarke) ambushes her during cross-examination at the security hearing. Despite her disappointingly little screen time, Blunt’s Kitty becomes a sturdy presence throughout Oppenheimer’s most difficult times. The opening scene shows Kitty sitting through his security hearings at one side of the frame. The security hearings managed to tear him down owing to his own moral qualms: He considered himself guilty but for completely different reasons from what the board was accusing him of. Kitty, who he immensely respects, reprimands him, ‘Did you think if you let them tar and feather you, the world will forgive you?‘

Jean Tatlock is a troubled psychiatrist and physician with communist ideals. While I was disappointed with the meagre screen time that Blunt receives, Florence Pugh’s character, even though performed splendidly, does not have the same impact as Blunt’s Kitty. Oppenheimer’s relationship with Jean is uncertain, stormy and sexual. Intense attraction and emotional volatility define their relationship. While Jean is extremely important to Oppenheimer’s life and is perhaps the reason for his left-wing political associations that get him into trouble, her lack of relevance to his scientific pursuits or the fact that she is not a persistent presence in his life explain the relatively little screen time of Pugh’s character.

Oppenheimer’s stance and its relevance

This film serves as a cautionary tale and takes a solid stance against the unthinking application of scientific theory that can have unfathomable consequences. The disconnection between the pursuit of science and our existence as social, political beings is rendered impossible. No pursuit is innocent and science cannot be pure and bereft of very human (or monstrous) motivations. While Oppenheimer sees the dangers of dropping such a bomb, he has rationalised his action by limiting his role to its creation. One gets a sense that even he knew he was lying to himself. Another way he rationalises his participation in the creation of the bomb is by claiming that the decision to use the bomb was not in his hands, nor was it his job.

One can see the complete realisation of the implications of an atomic bomb in Oppenheimer’s eyes as the yellow puffs of fire overwhelm the sky (if you are watching the movie in an IMAX theatre, the cinematic grandeur of the scene is unparalleled). Oppenheimer hears about the bombings through the radio. When he visits President Harry Truman, laden with immense guilt, he confesses, almost inaudibly: ‘Mr. President, I feel I have blood on my hands.‘

As a viewer, the alternating timelines (and hence, stories), rapidfire exchanges and the cerebral quality of the the film can get overwhelming. The convolutedness this results in can be discouraging. But one must remember why such a story needs telling. In a world as sharply divided and suspicious as today’s with escalating nuclear threats, a caveat depicting the absolute failure of policies of deterrance from the past serves as an important reminder. It enables one to ask evocative questions such as: how is patriotism noble if it implies unquestioning loyalty to one’s country at the cost of innocent human lives? What are the moral entanglements inherent in scientific theory and applications today and how can we learn from history? What does a nation owe to its scholars and knowledge-makers? Keeping these burning questiond in mind, the film is certainly worth multiple viewings.

About the author(s)

Shakti (she/her) is an English major and an aspiring tea sommelier. She loves reading poetry and drama and can be found with a Kindle most time. She intends to become a teacher of humanities and is passionate about literature, films, politics, and history. In her free time, she has been caught watching cringe content, however, she fervently denies these claims.