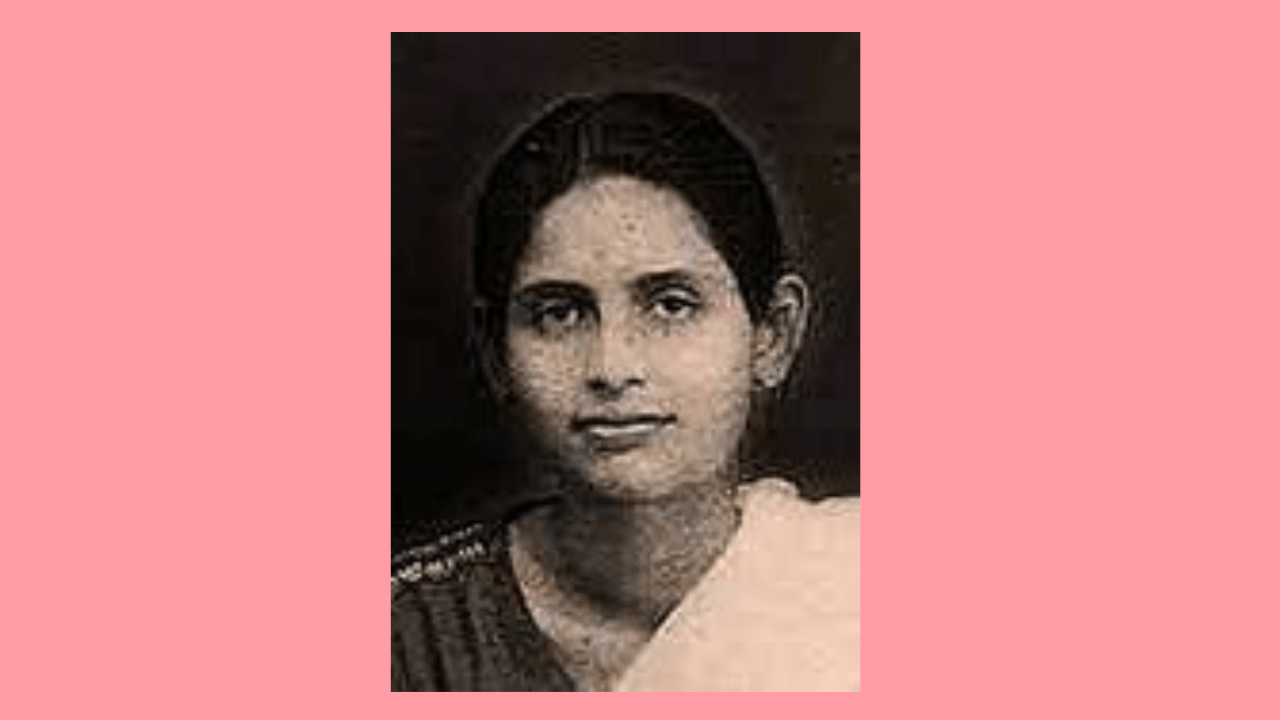

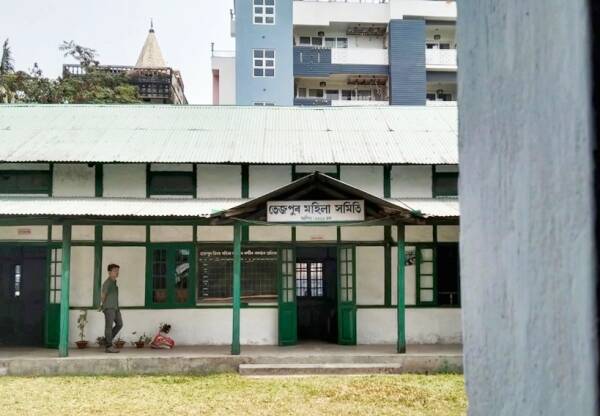

Borma Mina Agarwala, affectionately known as ‘Mambu’ to the hundreds whose lives were touched by her voluntarism, was a women’s rights activist hailing from Assam. Her life and work has had a significant impact on women’s empowerment in the North East, sending a ripple effect of change across India. For over 50 years, between 1940s to the 2000s, she worked for Tezpur Mahila Samiti and ushered in revolutionary changes in her community of women.

Gandhian in her core ideologies, she closely followed in the footsteps of her foremother and founder of Tezpur Mahila Samiti, ‘Agni-Kanya’ Chandraprabha Saikiani, and reconstituted the Samiti in her stead. She worked with grassroot communities of rural women, and volunteered extensively into the rural villages of Mangaldai and Behali as the President of the District Social Welfare Board.

Early life, education, and inspiration

Daughter of Nagendra Nath Baruah and Hemlata Baruah, residents of Tezpur district, Mina Agarwala was born on December 15, 1924. At a very young age, Mina came under the guidance of Bishnu Prasad Rabha, a pioneer of art and culture and popularly known as Kalaguru. As a result, she was trained in music and dance from a very young age.

Alongside cultural practices, she continued her formal education till secondary levels. Soon after, at a tender age of 15, Mina Agarwala was married off and her formal education came to a staggering halt. She was married to Kamala Prasad Agarwala, hailing from a renowned family and brother to famous Rupkonwas Jyoti Prasad Agarwala. After her marriage, she became mother to two daughters and a son, and had to immerse herself into household work.

Her husband made an effort to continue her education by appointing a home tutor to teach her English. However, as it went with most women in her position, household work demanded her attention and energy in its entirety and she was unable to learn much from her tutor, leading to an end to her education of all manner. However, even as a housewife, she devoted her attention to social work and became thoroughly engaged with voluntary work.

Soon she divided her time and her work between her family at Poki and her social work endeavours at the Samiti. Throughout her life, Mina had been a voracious reader and was well-read in many arenas.

Soon she divided her time and her work between her family at Poki and her social work endeavours at the Samiti. Throughout her life, Mina had been a voracious reader and was well-read in many arenas.

Mina Agarwala’s contribution, voluntarism, and feminist activism

Gandhian in ideology, she wholeheartedly dedicated herself and her life’s work to the cause of the women and the Samiti. She worked hard to gather funds and did not accept a single penny in the initial few decades as personal remuneration. Only much later, once the Samiti had significantly expanded its reach and had started to work on bigger projects, she started earning a small portion for herself. Her self-sacrifice and belief in her work made her stand out as a remarkable figure of leadership and a feminist icon. Her ideologies were informed by the spirit of secularism and strictly adhered to non-sectarian ethos.

As the president of Tezpur Mahila Samiti, she championed women’s empowerment by equipping them with vocational training and agency. She sheltered and helped women who were victims of natural disasters, such as floods, earthquakes, and other misfortune. She also tried to relocate and reestablish survivors of regional, communal violence so that they could reintegrate themselves in a new community.

As the president of Tezpur Mahila Samiti, she championed women’s empowerment by equipping them with vocational training and agency. She sheltered and helped women who were victims of natural disasters, such as floods, earthquakes, and other misfortune.

She worked with these women and arranged for rehabilitation programmes, counselling facilities, and built from the ground up a strong network of support structures to reestablish these women into the community. Throughout her lifetime, Mina also supported and helped women who were subjected to violence and abandonment in the matters of dowry, and other patriarchal subjugation.

Through tenuous hardwork and perseverance, she transformed Tezpur Mahila Samiti as a platform for amplifying women’s voices and giving them the agency and opportunity to empower themselves and live their lives free of patriarchal control. She battled with prejudices and societal disdain towards her work and continued to participate in social work with utmost dedication and vigour. At a time when women working outside their homes were heavily criticised and looked down upon, Mina managed to not only work as the President of the Samiti but also, through her work, laid out a strong foundation for women’s upliftment and communal support. She inspired women to seek out literacy, and means of employment and showed them a way to fight against ignorance, dependency, and patriarchal subordination. In the Samiti, legal support was also offered to women who were entangled in divorce cases or any other forms of marital entangles.

At a time when women working outside their homes were heavily criticised and looked down upon, Mina managed to not only work as the President of the Samiti but also, through her work, laid out a strong foundation for women’s upliftment and communal support.

Another one of Mina Agarwala’s biggest achievements was sheltering Tibetan refugees from Chinese atrocities and rehabilitating them in her community. In 1959, she mobilised the workers of the Samiti and took initiative to welcome the Tibetan refugees. The women of the Samiti organised a truck and travelled down Missamari to bring the refugees back with them. They offered a great deal of support and social, structural, and organisational aid to the women who were escaping the violence of the Chinese war. In 1962, she even organised a fundraiser for the Tibetan refugees, as a contribution to the National Defence Fund.

Perhaps, it could be said that Mina Agarwala’s most significant contribution was to fight against Triple Talaq on behalf of Assam’s Muslim women. In 2002, Tezpur Mahila Samiti collaborated with Muslim Women’s Forum and organised a public hearing regarding several issues concerning the Muslim women of Assam. They addressed Triple Talaq, refusal to pay Mehr, dowry problems, and other marital issues. This public forum was named as ‘Giving the Voiceless A Voice’.

She also strongly believed in the need for education of local children. Within the campus of Tezpur Mahila Samiti, she started a vernacular primary school called ‘Sisu Bharati’ in order to promote and encourage mothers to send their children to school and get educated.

On 24 July, 2014, Mina Agarwala breathed her last at the age of 90. In her wake, she left behind an insurmountable legacy of groundbreaking feminist activism and voluntarism. In her lifetime, Mina Agarwala was recognised for her hardwork and was awarded the prestigious Amal Prabha Das Memorial Award, Nari Shakti Award, and Janaki Devi Bajaj Award. Yet, her contribution remains hidden out of mentions and recognitions within the larger feminist discourse that emerged in India during the 80s.

About the author(s)

Debabratee (she/they) is a student of English Literature at Jadavpur University. When they are not found reading or writing, they are found running after their pet dog and cuddling with him. They are avid binge-watcher of all kinds of OTT content and like to dissect and analyse them in their free time.