The Emergence of Women’s voices in the early twentieth century was a significant shift in print culture. Plain and raw words were written by nameless women addressed to the editor of the Hindi magazine Chand. This was the milieu when women had begun writing letters and small notes of their personal grievances.

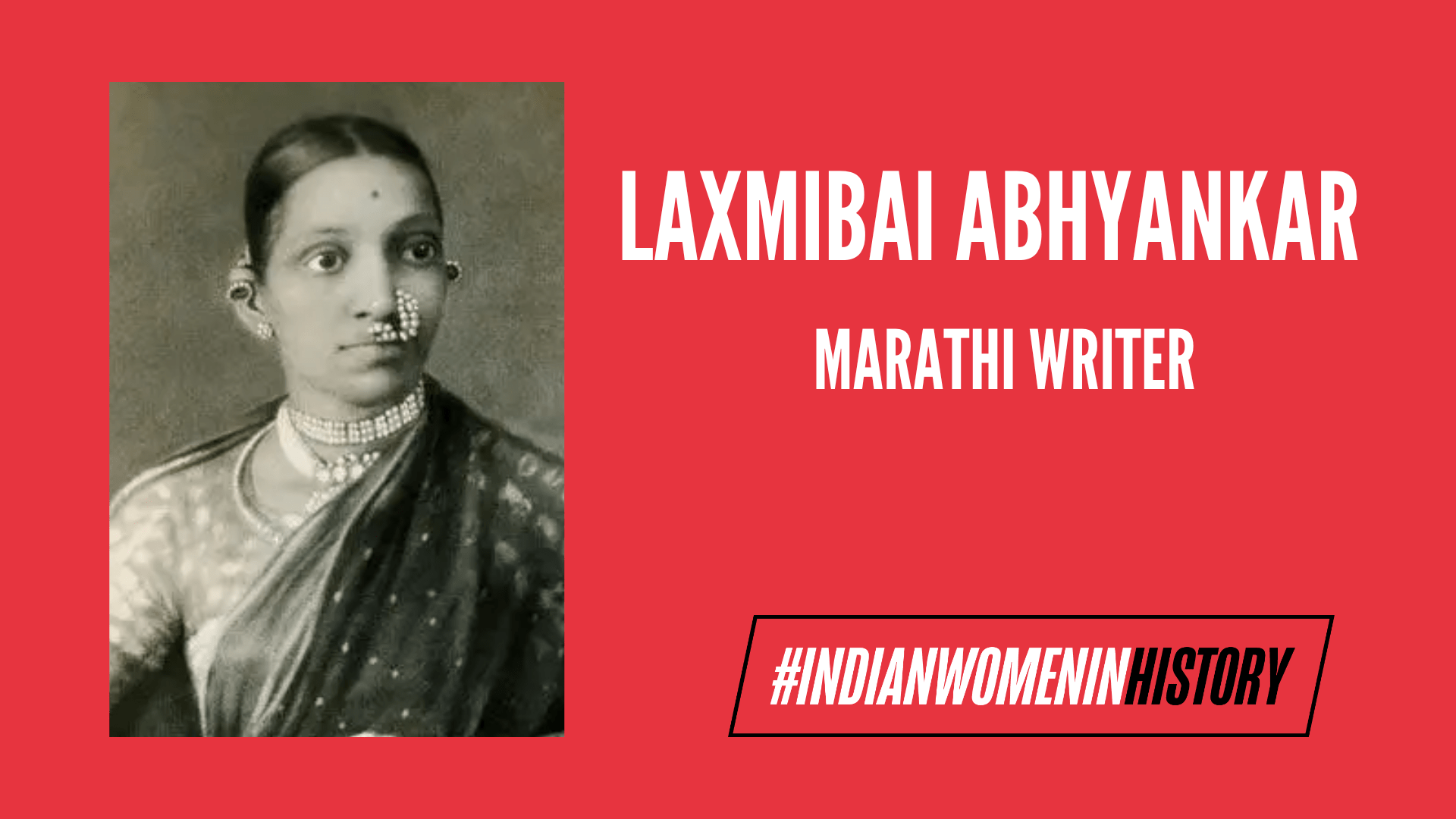

In turbulent times that overlooked the changing rifts of widow remarriage and education for women, the social and independent moment was facilitated by magazines and newspapers. One of the key literary prolific figures that emerges out of this timeline is Laxmibai Abhyankar – a writer, poet, and one of the very first women whose short stories made it to the publications of popular Marathi magazines in the 1900s.

The influences and principles of her writing were a byproduct of her position in the Nav-matvadi social movement, a resistance that aimed to reject traditions and customary practices that subjugated women. The context within which her writing emerged was moulded and glazed by her familial circumstances, as her grandfather was a pioneer of the movement as well.

The stories and prose of Laxmibai Abhyankar traverse and navigate the social ills that plagued her times. Her writing possessed a strong hold over the contentions of child marriage, the ostracisation of widows, and women kept out of educational institutions among other things. In one of her short stories, she writes, “We interpret propriety as slavery when defining the daughter-in-law’s conduct.” She then proceeds to write extensively on how the daughter-in-law, essentially a woman brought into the thresholds of a new house, is subjected to discipline and mistreatment.

“We magnify her every action, her every mistake, real or imagined, as an excuse to constantly maltreat her. How should one describe such behaviour by a mother-in-law,” she writes. Some of these lines alone continue to be a testament to how Laxmibai Abhyankar was a woman ahead of her times, delving and dissecting into the internalised misogyny and patriarchal family unit that governs the Indian household, she delicately but fiercely underlines the grief of the married woman.

The interiority of Laxmibai’s characters wasn’t narrow and reductive, nor were they dealing in the absolutes of naivety and bravery. Instead, her characters are often complex and nuanced, navigating the lives of both empowerment and self-doubt. The women in her stories are oftentimes unlikeable, resilient and timid, all at once. The authorial voice of Abhyankar speaks to you in many ways, urging the reader to introspect and bring into consciousness the question of women and their myriad lives.

Her short stories went on to be published in popular Marathi magazines such as Manoranjan, Karmanuk and Vividhyanvistar. These stories were met with sharp and scathing critique by a few literary contemporaries, mostly men, who resisted her tenor against the debasing ritualism that shrouded the lives of widowed women. Even with Sati outlawed in 1829, the social reforms improving the living conditions of women were rather very slow-paced.

Social reform movements were still mostly spearheaded by men, with the exception of Savitribai Phule. Therefore in the print culture of the time, hardly any attention was given to women’s issues and their rights, even the women’s magazines oftentimes had men writing and advocating for women’s education.

What followed this evocation of male writers was the era of anonymous female voices, forging a community of editorials and column sections airing grievances. The shaping of the female consciousness in the early twentieth century was followed by prolific female writers like Laxmibai Abhyankar making it to the public domain of authorship.

Feminist Literature in the early 1900s has always had a very fraught and troubled framework, fuddled with controversy and censorship. Another renowned contemporary of the aforementioned social milieu was Malati Bedekar. Her stories erupted with women who were the antithesis of subservience, much like the works of Laxmibai Abhyankar.

She plunged beyond conventions and transcribed the Indian woman in a body of emancipation and intersectionality. Her books explored the position of educated women within families and novel relationships of women in lesbian relationships. She was met with scathing critique, however, her guided anonymity and pen name protected her from the likes of male allies who believed her writing to be overly critical and contemptuous – a sentiment that rings true even for Abhyankar’s works.

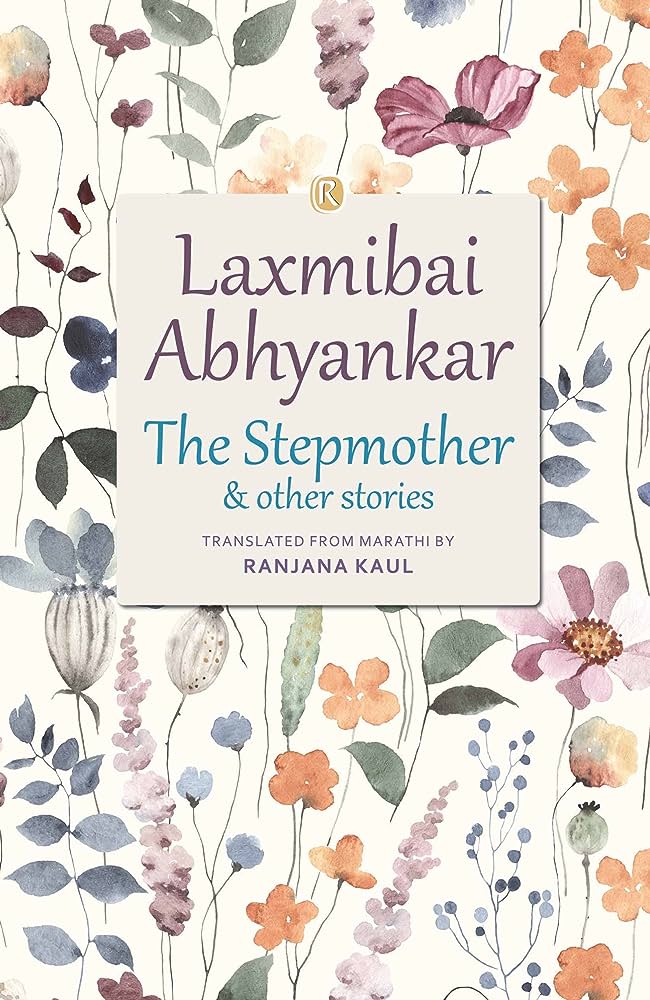

Nearly 55 years after Laxmibai Abhyankar’s death, Dr Ranjana Kaul has translated to English her only surviving text – “The Stepmother and Other Stories,” comprising eight short stories that travel into the urban and rural households of Maharashtra, where the question of women’s emancipation was only just coming into existence.

The women of these stories belonging to the worlds of these pioneering literary figures continue to decline in popularity and significance. There is little to no recorded history on the lives of women like Abhyankar, despite the testimony and adage of her granddaughter, Dr Ranjana Kaul.

The hidden archives of her legacy were only discovered when her granddaughter chanced upon her grandmother’s works at the age of 17. Women’s histories and complexities have become a relic of the past, even with extensive research on feminist literature in pre-colonial India, the catalogue remains small and insufficient in comparison to its male counterparts.

Nearly 55 years after Laxmibai Abhyankar’s death, Dr Ranjana Kaul has translated to English her only surviving text – “The Stepmother and Other Stories,” comprising eight short stories that travel into the urban and rural households of Maharashtra, where the question of women’s emancipation was only just coming into existence.

While it is unfortunate that this is the only surviving text that stands the test of time, the critical reader must tap into reviving and uncovering many such texts of insurgence that lie either hidden or lost in the memory of erasure and subjugation.

About the author(s)

Rida Fathima is a twenty-year-old Literature student at Azim Premji University with an interest in literary theory, film criticism, Marxist historiography and oral archives. She is interested in critiquing and analysing media through a feminist anti-capitalist lens.

Dear Rida, thank you for this unexpected, but very welcome review of stories . Bless you for your sensivity. More power to you pen. Ranjana Kaul