In 1992, film critic B. Ruby Rich declared the coming of a new queer film wave in her essay for The Village Voice, “A Queer Sensation.” This was a film wave that was independent, enigmatic and catered to the issues most relevant to contemporary gay men and lesbians. Rich claimed that it encompassed layers of irony and style which could be described as “Homo Pomo,” – films fixated and full of pleasure. Tracking their emergence, she wrote, “They’re here, they’re queer, get hip to them.”

Whether you agree with Rich’s characterisation or not, her essay was republished as a manifesto and then succeeded by her release of a book encompassing 27 essays on the history of a New Queer Cinema marked a critical moment in film history – her essay and the immediate reception it received meant that people were thinking of queer identities and aesthetics together in a manner that would lay the groundwork for the scores of queer filmmakers who followed after.

Rich drives the very explicit point home, that pleasure and politics more often than not, are an intertwined entity, the lines between the two are blurred, and one cannot exist without the other.

In her book, Ruby Rich outlines one of the early tensions in avant-garde queer cinema, the tension of pleasure and politics, the tension between positive and negative representations of the community, and the strife between commercial films and independent productions. In a section, she reminds the reader of the highly independent and experimental filmmaking of the postwar US cinema, marked by the works of Andy Warhol, Jack Smith and Gregory Markopoulos, she also draws attention to the 70s and 80s lesbian feminist cinema of Barbara Hammer, Su Friedrich and Lizzie Borden that was an amalgamation of radical politics, sex and humour.

Rich drives the very explicit point home, that pleasure and politics more often than not, are an intertwined entity, the lines between the two are blurred, and one cannot exist without the other.

Rich’s essay on Cheryl Dune’s The Watermelon Woman celebrates the film’s humour to comment on issues of racism in lesbian culture and historiography. She recalls fondly of how such films boasted of a robust audience of dates, lovers and women excited for its screening.

Rich’s chapter on lethal lesbians in which she embraces the homicidal lesbians of the nineties (with Thelma and Lousise and Bound) – this analogy when put in the context of early lesbians in mainstream films becoming the victims of violence, makes sense, the nineties lesbians team up as partners and kill another man. Rich in her essay then makes murder analogous to Marriage stating that bloodshed became a new form of lesbian courtship and murder, the new foreplay.

While Ruby Rich recognises the stakes of inverting power imbalances like this and how it might obscure the material and real violence queer individuals face, she argues that some of these films are much better than their punishing peers, that enable us to visualise queer cinema beyond the fulfilling the fantasies of a politically correct queer audience. The question then persists today, are we able to envision a queer cinema that reaches beyond the fantasies of a politically correct audience?

Even in the South Asian context, the mainstream’s fixation with portraying the tortured lives of queer identities on screen seems to be catering to the sympathies of a heterosexual audience than an LGBTQ+ demographic, Made in Heaven, fulfils the ambit of ‘pleasure in strife,’ where pleasure for its queer characters doesn’t exist outside the umbrella of violence, tension or external threats.

The tension between commercial and independent filmmaking is very evident in the Indian film industry. Even though Badnaam Basti, a queer film dating back to 1971, had a nuanced and ambiguous representation of sexuality and intimacy, it had a more authentic and raw portrayal of queer cinema than its contemporary counterparts.

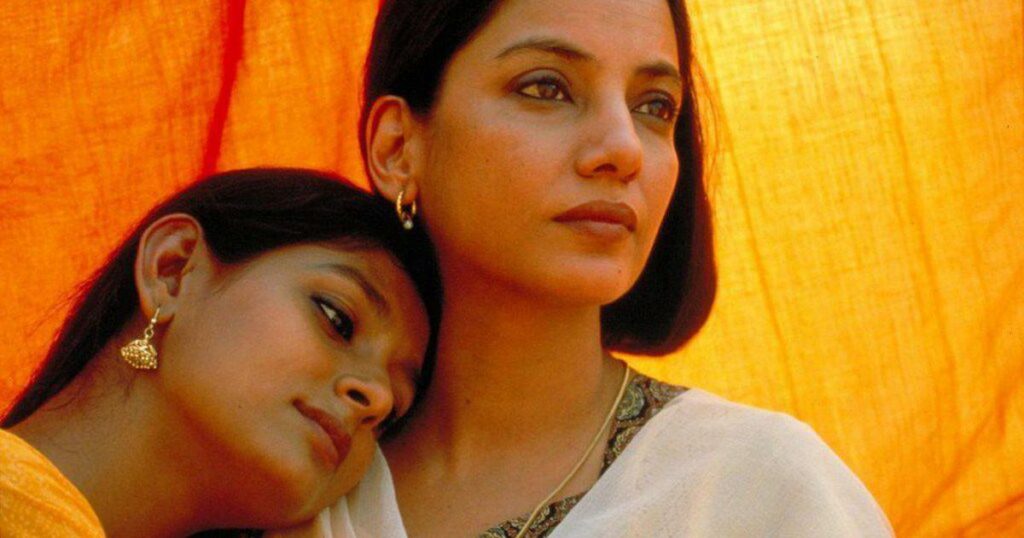

Deepa Mehta’s Fire, a trailblazer in Indian lesbian cinema encrypts the world of female and lesbian desire in the fire pit of patriarchy – while mainstream films like Badhaai Do have made some strides in moving away from the traditional genre of tragedy and embracing the realm of comedy and queer cinema, the same cannot be said about its contemporaries.

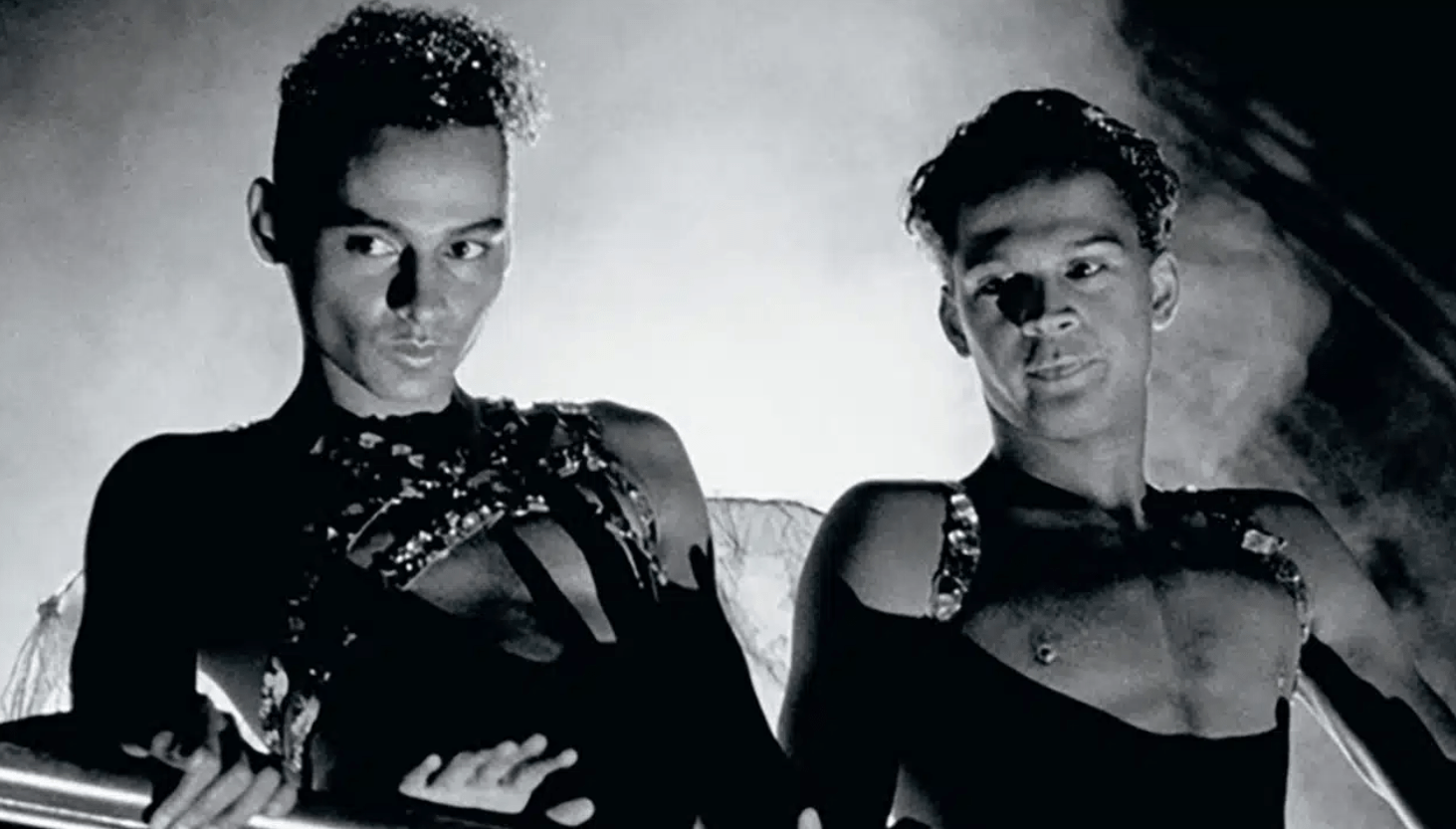

Riyad Vinci Wadia’s Bomgay from 1996 entails one of Indian cinema’s first gay scenes of Rahul Bose having sex in the library. It is a film that is playful, explicit and engaging in its delivery. With such a myriad archive of early queer cinema in India and South Asia, it becomes necessary to consider Rich’s argument in New Queer Cinema, one that is of reimagining gay aesthetics outside the fold of the Indian Family Unit.

Some of these new-age films, while arguably pragmatic, don’t pose any real threat to the patriarchal heteronormative order; more often than not, they aim to assimilate with the order itself. This, of course, is a very obvious symptom of a heterosexual Asian culture that seeks to maintain the power dynamics it holds up. Yet, there is an urgency to reach beyond these obtuse boundaries of desire.

It also feels disingenuous to draw parallels between a predominantly European filmography and a South Asian one, given its differing politics of criminalisation and legalisation, these are questions queer filmmakers seem to be constantly in the middle of – and yet there’s the deep-seated need for storytelling, both experimental and provocative, independent and nouveau in its rendition of queer stories, lives of pleasure and experiences.

Reading Ruby Rich’s New Queer Cinema is an invigorating read, the 27 essays reflect upon the wide-reaching landscape of queer filmmaking, and revisiting this landscape in the wake of new Indian Queer cinema urges the reader to look inward, at our own LGBT+ filmography and consider the visual aesthetic of desire that seeks to traverse beyond the binaries of mere representation and violence.

About the author(s)

Rida Fathima is a twenty-year-old Literature student at Azim Premji University with an interest in literary theory, film criticism, Marxist historiography and oral archives. She is interested in critiquing and analysing media through a feminist anti-capitalist lens.