Johanna Hedva is a genderqueer Korean-American writer, musician and artist. They have written several novels and essays at the intersection of gender and disability. In their much-talked-about essay, the ‘Sick Woman Theory,’ (originally published in 2016), Hedva draws on their gendered and racialised experience of living with chronic illness to create a new, intersectional feminist theory that focuses on the lives, agency, and constraints of people who are living with diseases and disabilities.

They based their theory on contemporary political movements, particularly the Los Angeles Black Lives Matter protests in 2014 and their incapability to take part in the demonstrations. Hedva creates a space that is at once in tune with the second-wave “personal is political,” maxim and a more intersectionally expansive, and explicitly queered twenty-first-century feminism. They justify their use of the term “woman,” in the title by queering the “woman,” label through trans, nonbinary, and genderqueer subjectivities.

According to the Sick Woman Theory, numerous kinds of political dissent are internalised, lived, embodied, painful, and undoubtedly unseen. Sick Woman Theory, which draws inspiration from Judith Butler’s writings (amongst many other writers) on precarity and resistance, redefines existing in a body as something that is fundamentally constantly vulnerable. We need to reshape humanity around this truth because the premise sets that a body is defined by its vulnerability, rather than just briefly impacted by it.

Questioning the definition of political

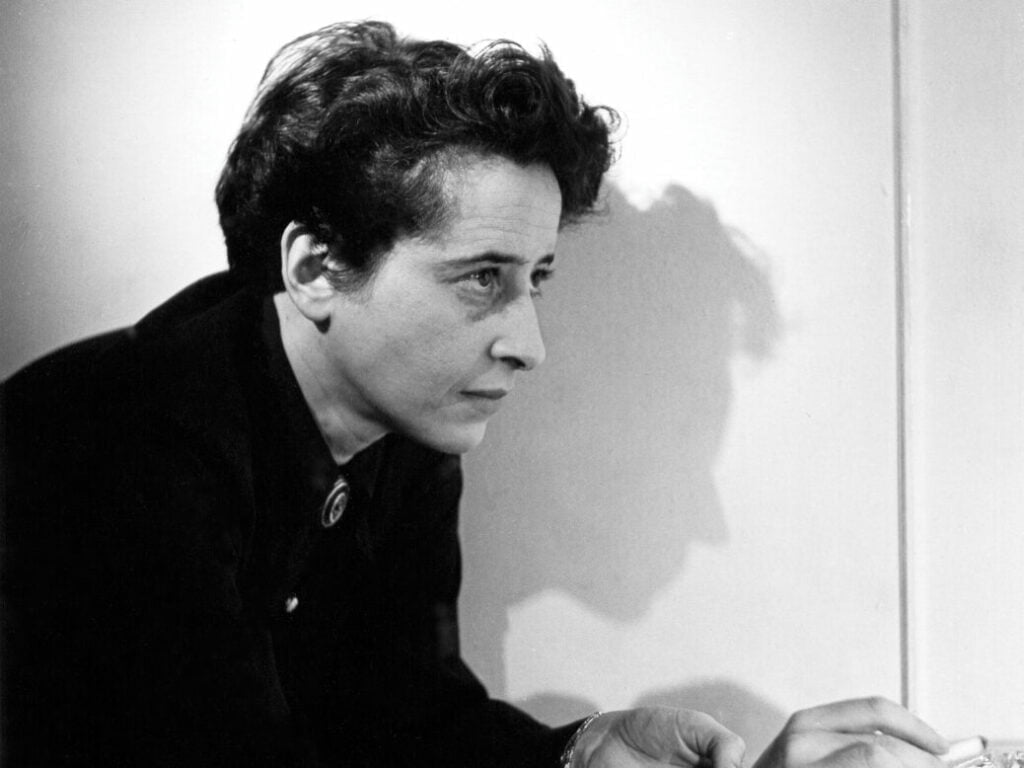

In the first section of their essay, Hedva discusses the definition of Hannah Arendt’s ‘political,’ and ‘visible,’ and how it renders a huge percentage of the population to be apolitical and invisible, just because they cannot physically bring their bodies onto the streets. Does a sick woman raising her fist in her bed not count because she’s physically not participating in the Black Lives Matter protest right outside her house?

Hedva points out how Arendt’s ‘political,’ relies on a ‘public,’ space where bodies must gather but what that implies is that there is a ‘private,’ and what happens there isn’t political. It creates a dangerous binary of public/private and visible/invisible. For instance, then, are you not racist if you use racist slurs in a private conversation because it’s ‘private,’ and ‘invisible?’

Arendt’s definition of the ‘political’ reflects the worries of her era where if everything became political, then nothing remains political. However, it cannot be denied that ‘the personal is political’, which is to say the private and the invisible must also be included in the movement. Oftentimes, the people for whom protests are held are unable to be visible as political bodies because of who’s in charge of a public space. Arendt’s definition fails to take that into account as well.

‘So, as I lay there, unable to march, hold up a sign, shout a slogan that would be heard, or be visible in any traditional capacity as a political being, the central question of Sick Woman Theory formed: How do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can’t get out of bed?’, writes Hedva.

The binary of ‘sickness’ and ‘wellness’ in Sick Woman Theory

In the following sections of their essay, Hedva emphasises how the concept of ‘wellness,’ is a construct of capitalism, which treats the state of being as the standard and those who are not in it as the ‘sick.’ The theory attempts to overturn the idea of ‘wellness,’ as the default and proposes that our ‘body and mind are sensitive and reactive to regimes of oppression,’ meaning that we all share historical trauma (for instance, colonialism, slavery, etc.) that in turn in making us and the world as sick.

Capitalism as a concept requires bodies that are well enough to work and it thrives on exploiting these bodies for profit. However, when a body is not ‘well enough,’ to work, their suffering and consequent care are invisibilised and denied. The exploitative nature of capitalism resigns these bodies to die because they are merely expensive or simply useless to the system.

Hedva theorises that the body is defined by its vulnerabilities and not temporarily affected by them. They say that a ‘sick woman,’ is anyone who is ‘denied the privileged existence – or the cruelly optimistic promise of such an existence.’ The identity of being a ‘sick woman,’ applies to anyone who shares the trauma of not being seen, it applies to the bodies of ‘women, people of colour, poor, ill, neuro-atypical, differently abled, queer, trans, and genderfluid people.’ The sick woman is who capitalism thrives on.

Capitalism as a concept requires bodies that are well enough to work and it thrives on exploiting these bodies for profit. However, when a body is not ‘well enough,’ to work, their suffering and consequent care are invisibilised and denied. The exploitative nature of capitalism resigns these bodies to die because they are merely expensive or simply useless to the system.

This is precisely why the binary of so-called ‘wellness,’ and ‘sickness,’ is dangerous. By deeming ‘wellness,’ as the default state of being, we are assuming that ‘sickness,’ is temporary. Which, in turn, implies that the care and treatment for sickness is temporary. This idea that sickness is temporary is what allows capitalism to perpetuate itself.

In a powerful conclusion, Hedva suggests, that to combat this, one should care for each other and care for themselves and that is the most anti-capitalist protest they can take part in. If we start thinking of ‘sickness,’ as the default state of being, we will have to acknowledge that taking care of one’s own and each other’s sickness is also our default role in society.

It will naturally lead to us forming a community and collectively working towards enduring an unbearable reality together. In such a society, there will be no place for working or exploiting bodies for profit and capitalism will have no choice but to cease to exist.

References

- Sick Woman Theory by Johanna Hedva, originally published in Mask Magazine in 2016, adapted from their lecture, ‘My Body Is a Prison of Pain so I Want to Leave It Like a Mystic But I Also Love It & Want It to Matter Politically.’

About the author(s)

Sharanya Gopalakrishnan is a recently graduated journalism student from Flame University. She

loves reading and watching cringe TV shows. She hopes to publish her own novel someday.