Trigger Warning: Mention of Suicide

Saima Shafi, a 21-year-old college student, initially thought her feelings of constant stress were merely the result of academic overwork and exhaustion. Little did she know that she was grappling with a condition that would turn her life into a never-ending cycle of emotional turmoil and physical symptoms.

‘Sometimes it seems like you’re on a seven-day bender where you’re making the worst possible decisions of your life; you are sort of setting your life on fire on purpose,’ is how Saima described her experiences with PMDD.

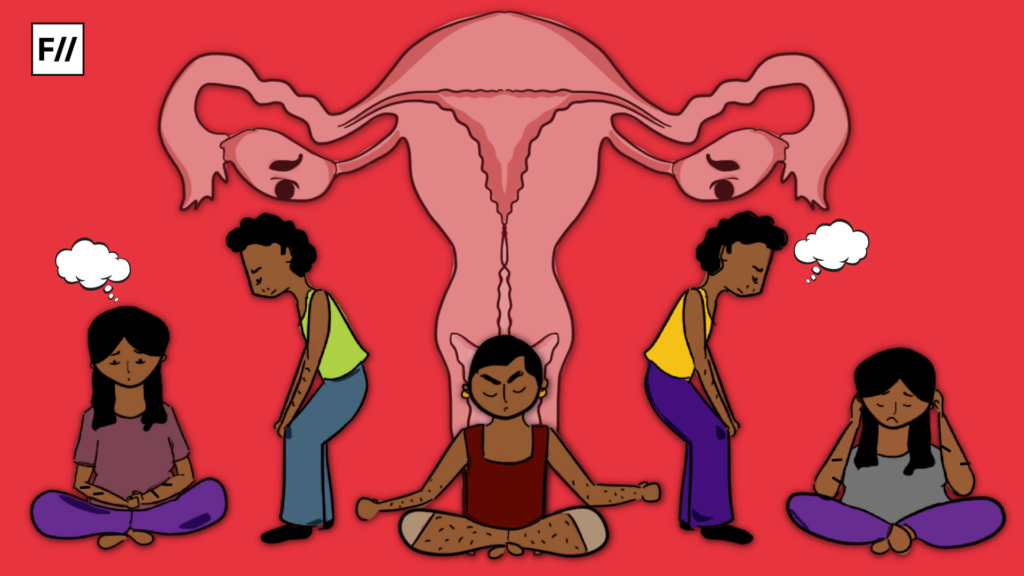

PMDD, or premenstrual dysphoric disorder, is a severe form of premenstrual syndrome that affects a small percentage of women. Saima’s description highlights the intense emotional and psychological impact that PMDD had on her life, making it feel like a never-ending cycle of self-destruction.

This disorder is characterised by extreme mood swings, irritability, depressive episodes, suicidal thoughts, feelings of hopelessness etc often leading to strained relationships and difficulty functioning in daily life.

‘It felt like getting on a hamster wheel and not being able to get off,’ Saima recalls, describing her early experiences. For many young adults, moments of stress and anxiety may come and go, but for Saima ‘these feelings seemed relentless.’ ‘My daily routine was consumed by a constant battle with my mind as stress and anxiety began to take a toll on my physical health,’ she explained further.

Eventually, she reached a breaking point and decided to take an uncharacteristic short leave of absence. However, her mood didn’t improve, and she soon found herself waking up each morning with overwhelming anxiety, leading to a gradual withdrawal from her social life. ‘I would essentially do a disappearing act so I wouldn’t have to be around people,’ said Saima. Her struggle with anxiety and withdrawal from her social life took a toll on her overall well-being. She felt trapped in her thoughts and longed for a way to escape the overwhelming burden she carried.

Saima’s occasional fantasies of never waking up highlight the depth of her emotional distress.

However, the mystery of Saima’s condition extended beyond her psychiatric symptoms. She began to experience odd physical patterns as well. Bloating and fatigue would accompany her through certain phases of her life, and she started to sleep excessively. These physical symptoms added to Saima’s already overwhelming emotional distress, leaving her feeling even more trapped and desperate for relief. The combination of her psychological and physical struggles made it increasingly difficult for her to find a way to break free from the burden she carried.

While talking to Saima’s mother, Gulshan Shafi, she said ‘Saima experienced extreme mood swings, ranging from aggression to depression. She would often become irritable and lash out at loved ones, only to later sink into deep bouts of sadness and hopelessness.’

These mood swings took a toll on Saima’s relationships, causing strain and misunderstandings with her family and friends. It became evident that her emotional instability was not only affecting her well-being but also impacting those around her, further intensifying her feelings of isolation and desperation.

Her mother also added that ‘Saima is a passionate gardener; she would shop erratically, impulsively buying plants that were out of season. Then I started noticing her increasingly strange behaviour as well. She would spend hours obsessively tending to her garden, neglecting other responsibilities and social interactions. Her once vibrant and colourful garden became a chaotic mess, mirroring the turmoil within her mind.’

Saima herself considered the possibility of other severe mental disorders, given the cyclical nature of her emotional ups and downs. ‘I used to spend two weeks each month trying to mend the damage caused by the previous week: the arguments with loved ones, the neglected home, and the academic setbacks,’ said Saima. It wasn’t until she experienced what she calls a ‘mini-breakdown,’ that she realised the recurrence of all these symptoms was intimately tied to her menstrual cycle.

Saima sought medical help and was diagnosed with PMDD, a severe form of premenstrual syndrome. She learned that hormonal fluctuations during her menstrual cycle were triggering her emotional and behavioural changes, leading to the recurring symptoms she had been experiencing. With this newfound understanding, Saima was able to explore treatment options and develop coping strategies to better manage her condition.

By working closely with her healthcare provider, Saima was able to find a treatment plan that included medication and therapy. Through this comprehensive approach, she began to experience significant improvements in her symptoms and overall quality of life.

Saima’s journey toward understanding her condition is not unique. Many women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder face the challenge of finding a proper diagnosis and effective treatment. While the exact cause of PMDD remains a topic of research, hormonal fluctuations and genetic factors are believed to play a significant role in its development.

In addition to seeking professional help, Saima also found support in online communities and support groups, where she could connect with other women who were going through similar experiences. These platforms provided a safe space for sharing coping strategies and offering emotional support, further reinforcing the importance of community in managing PMDD.

According to the International Association for Premenstrual Disorders, a new global study finds an alarming number of women, about 34 per cent with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) having attempted suicide to escape the debilitating symptoms. This report also says that women who are neurobiological sensitive to hormone changes, as in the case of PMDD, may be at increased risk of not only suicidal thoughts but also suicidal behaviour.

Mehak, who has been living with PMDD for the past five years, expressed the profound impact it has had on her life, particularly in her relationships with loved ones. She shared how PMDD symptoms often caused intense mood swings and irritability, leading to conflicts and misunderstandings.

‘There have been times when it made me feel as though I was teetering on the brink of insanity. During those two weeks of the month, I simply do not recognise myself, and what’s even more concerning is that this time frame of emotional turmoil seems to be gradually extending, at times even becoming longer than expected,’ Mehak told FII.

She recounted her frustrating journey seeking medical help, where some professionals misdiagnosed her condition as depression, prescribing medications, while others dismissed her concerns, attributing them to mere overthinking. ‘I didn’t want to live; I was angry at everybody for no reason; there was no reason for this anger that I felt.’

The lack of proper diagnosis and understanding only intensified her feelings of despair and hopelessness, making it even more challenging for her to find the help she desperately needed.

‘I used to sleep for 12 to 14 hours a night, wake up, have breakfast, and then immediately feel the overwhelming need to take another nap. I found myself struggling to keep my eyes open throughout the day. I experienced multiple panic attacks daily, and the weight of depression was utterly exhausting.‘ said Shagufta Hassan. Her friends and family would often tell her to just “snap out of it,” or “think positive,” but she knew deep down that there was something more going on.

Despite the dismissive attitudes around her, she couldn’t ignore the toll it was taking on her physical and mental well-being. ‘There was an overwhelming sense of shame and stigma because of my behaviour. It’s especially challenging when you don’t understand what you’re dealing with. I believed I was just messed up. It wasn’t until I turned 27 that I truly realised how severe it had become.’

‘My partner at the time, broke up with me, describing it as living with a completely different person for weeks. I was devastated by the breakup, and it served as a wake-up call for me to seek professional help.’ Shagufta said to FII. However, after therapy and support, Shagufta was in a better position to understand the experiences associated with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder.

Seeking medical attention helped these women to go back to their daily lives, however, a large section of women in Kashmir and outside are still uneducated and unaware of their menstrual and reproductive health. The lack of research on Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder has also left the mental healthcare systems inaccessible and ineffective for women seeking support and diagnosis.

About the author(s)

Masrat Nabi is a journalist whose work focuses on politics, gender, culture, and social issues in India.