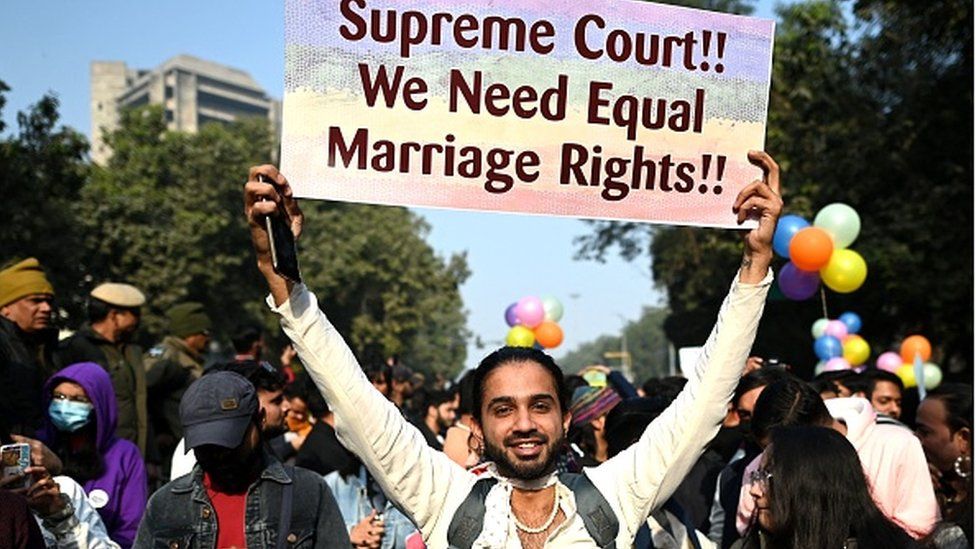

On Tuesday, October 17, the Supreme Court issued its verdict on the marriage equality case. The court came to the conclusion that it must be the Parliament that must decide whether or not to allow for marriage equality as a whole and that the judiciary cannot do so. Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul, Justice Ravindra Bhat, Justice Hima Kohli, and Justice P.S. Narasimha made up the bench, along with Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud. The CJI stated that a total of four rulings were handed down, ‘with a degree of agreement and a degree of disagreement‘.

The petitioners presented an argument that there is a fundamental right to marry the person of one’s choice, and the court must address any violations of that right. If the court deemed this to be a fundamental right (as it did in the 2017 Puttaswamy case), it would impose a duty on the government to uphold this right. The petitioners had also contended that the Special Marriage Act (1954), in its current form, discriminates against non-heterosexual couples since it denies them access to marriage institutions, which signifies inferiority and subordination.

Is marriage a fundamental right?

All five judges on the bench unanimously agreed that there is no such thing as fundamental right to marry. Marriage has existed since before there was a state, therefore it is not a product of legislation but rather of culture.

All five judges on the bench unanimously agreed that there is no such thing as fundamental right to marry

Marriage would have to be elevated to the same level as other rights in Part III of the constitution, which deals with fundamental rights, if there was such a thing as a fundamental right to marry. However, marriage is a ‘personal preference‘ that ‘confers social status‘ as opposed to other rights guaranteed in Part III. It is also not ‘enforceable rights, which the courts can compel the state or governance institutions to provide.‘

The minority view (which consists of CJI Chandrachud and Justice Kaul) argued that queer unions should be accepted by the state, even if they do not take the form of marriage. It is against Article 15 of the Constitution to restrict someone’s ability to enter a union on the grounds of their sexual orientation. A marriage is important because of the slew of rights it comes with, and for same-sex couples to benefit from the same entitlements, ‘it is necessary that the state accord recognition to such relationships,‘ the CJI said.

However, the majority of the bench maintained that ‘all queer persons have the right to choose their partners. But the state cannot be obligated to recognise the bouquet of rights flowing from such a Union.’ An entirely new legal framework will be required for the registration of such civil unions and establishing eligibility requirements, age restrictions, divorce and alimony rights, among other rights that are related to marriage. They argued that the mantle of figuring out such a framework falls on the legislative and not the courts.

Is the Special Marriage Act, 1954 unconstitutional?

When it heard the petitions in April, the Supreme Court decided that it would avoid discussing personal laws and instead focus on determining whether the Special Marriage Act of 1954 (SMA) could accommodate marriage rights for queer relationships. SMA was enacted in 1954 as a secular framework where the state is allowed to sanction unions instead of religion. This act was mainly intended to benefit inter-faith and inter-caste couples so they could enter a union without giving up their religious identities.

The court refused to declare the SMA unconstitutional and they also refused to amend it to read gender-neutral. It felt doing so would violate the legislative branch’s authority and have “cascading” effects on subsequent laws. The ruling states that ‘if the Special Marriage Act is struck down, it will take the country to the pre-independence era.’ It also argued that the SMA’s gender-pecific provisions would be impacted by a reading that is gender-neutral. For instance, under a gender-neutral structure, issues like a different legal age for marriage for men and women, divorce remedies, and maintenance would present significant difficulties.

However, some critics do seem to think that the SMA is not all that beneficial to women and amending it wouldn’t do any great harm to them. So, it seems like while the bench agrees that the act is not inclusionary, but they’re content doing nothing to change it and placing the responsibility on the legislative. Justice Kaul remained the only judge on the bench to refute Justice Bhat’s assertion that the SMA was only passed to permit heterosexual marriages.

Adoption rights for queer couples

The petitioners claimed that the Central Adoption Resource Authority’s (CARA) policies, which prohibit unmarried couples from adopting children together, discriminate against queer couples who are unable to legally marry. According to the rules, a couple can only be qualified to adopt if they have been married for at least two years. Queer people can adopt as single people on an individual basis. In his opinion, the CJI stated that current adoption laws discriminate against the queer community and are in violation of Article 14. He further stated that ‘marriage alone does not give stability to a household.‘

However, the majority opinion ruled against adoption rights for same-sex couples. The court notes that since there is currently no framework for protecting children in the event of a queer couple’s separation or death, it would not be in the child’s best interests to overturn the regulations. The Supreme Court seems to arrive at the same excuse for every question they’ve addressed in this judgement so far: our current legal framework cannot accommodate this.

The Supreme Court seems to arrive at the same excuse for every question they’ve addressed in this judgement so far: our current legal framework cannot accommodate this.

Queer individuals have been asked to put their rights on hold and they’ve not even been given any tangible timeframe or resolution as to when their rights will finally be recognised. So far, it just seems like the SC are taking their hands off the issue.

A small victory for the trans movement

The five-judge bench also dealt with the issue of marriage rights of transgender persons in heterosexual relationships. The ruling stated, ‘A person’s gender is not the same as their sexuality.’ Since a transgender person is able to participate in heterosexual relationships, just like a ‘cis-male or cis-female, a union between a trans woman and a trans man, or a trans woman and a cis man, or a trans man and a cis woman,’ can be registered under our current marriage laws. It further said that intersex individuals who identify as man or woman also have access to this right.

The Court’s recognition of transgender people’s ‘right to self-determination‘ was a small victory within this decision. The statement contradicts the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act of 2019, which declared self-identification ‘subject to certification by the State‘ (petitions filed in the wake of this statement have deemed this provision unlawful). Although the Court’s current conclusions may not be legally binding, they will hold significant weight in future proceedings.

What next?

A ‘high-powered committee‘ led by the Cabinet Secretary is to be formed to deliberate and establish rights for queer couples. The CJI also recommended that the Committee be made up of individuals from the queer community and professionals skilled in ‘handling the social, psychological, and emotional needs of persons belonging to the queer community.’ Additionally, he instructed the Committee to consult with members of the queer community before ‘finalising its decisions‘.

The Committee would discuss a number of entitlements that were reserved for heterosexual couples, including gratuities, joint bank accounts, pension payments, and ration cards.

The Committee would discuss a number of entitlements that were reserved for heterosexual couples, including gratuities, joint bank accounts, pension payments, and ration cards. Both majority and minority views agreed that discrimination was taking place in these situations where queer couples aren’t given the same benefits as heterosexual couples. However, the judges couldn’t agree on who should change these policies: the legislature and executive branch or the judiciary.

In conclusion, while this judgement did bring a lot of attention to the issue of same-sex marriage and marriage equality, it has not given any actionable right or recognition for queer individuals. Furthermore, it seems like the SC is playing it safe by giving some seemingly progressive statements but essentially, doing nothing to break the current status quo. It is also infinitely harder for individuals to get the legislative to table and pass a new policy than filing a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in the judiciary to amend an existing law. Therefore, this judgement does not benefit the queer movement greatly at all and in fact, their battle for marriage equality might have gotten a lot harder and longer.

About the author(s)

Sharanya Gopalakrishnan is a recently graduated journalism student from Flame University. She

loves reading and watching cringe TV shows. She hopes to publish her own novel someday.

It is obvious that the central govt is playing it safe. They want the courts to pass some kind of judgement so that the current ruling party doesn’t lose favor with its core support.