On the night of 28th September 2015, 18 people gathered outside the home of Muhammed Akhhlaq in the Bisara village of Dadri in Uttar Pradesh. As a response to the announcement of the local temple that a cow was slaughtered, they attacked Akhlaq and his son. While his son survived, Akhlaq succumbed to his injuries.

The lynching of Muhammed Akhlaq in Dadri has been etched into India’s consciousness as it marked the growing intensity of hate violence against Muslims in India, especially since 2014. Sadly, it did not stop after the brutal murder of Muhammed Akhlaq. The weaponisation of food has been a constant narrative in Hindutva politics, leading to the isolation of the Muslim community and the death of many of its members. While the cow became the political symbol of the ruling party, it was the symbol of fear to the Muslims of the country. The systemic attempt to homogenise India’s culinary practices is a fascist effort – one that is imposed through force and propagated through fear.

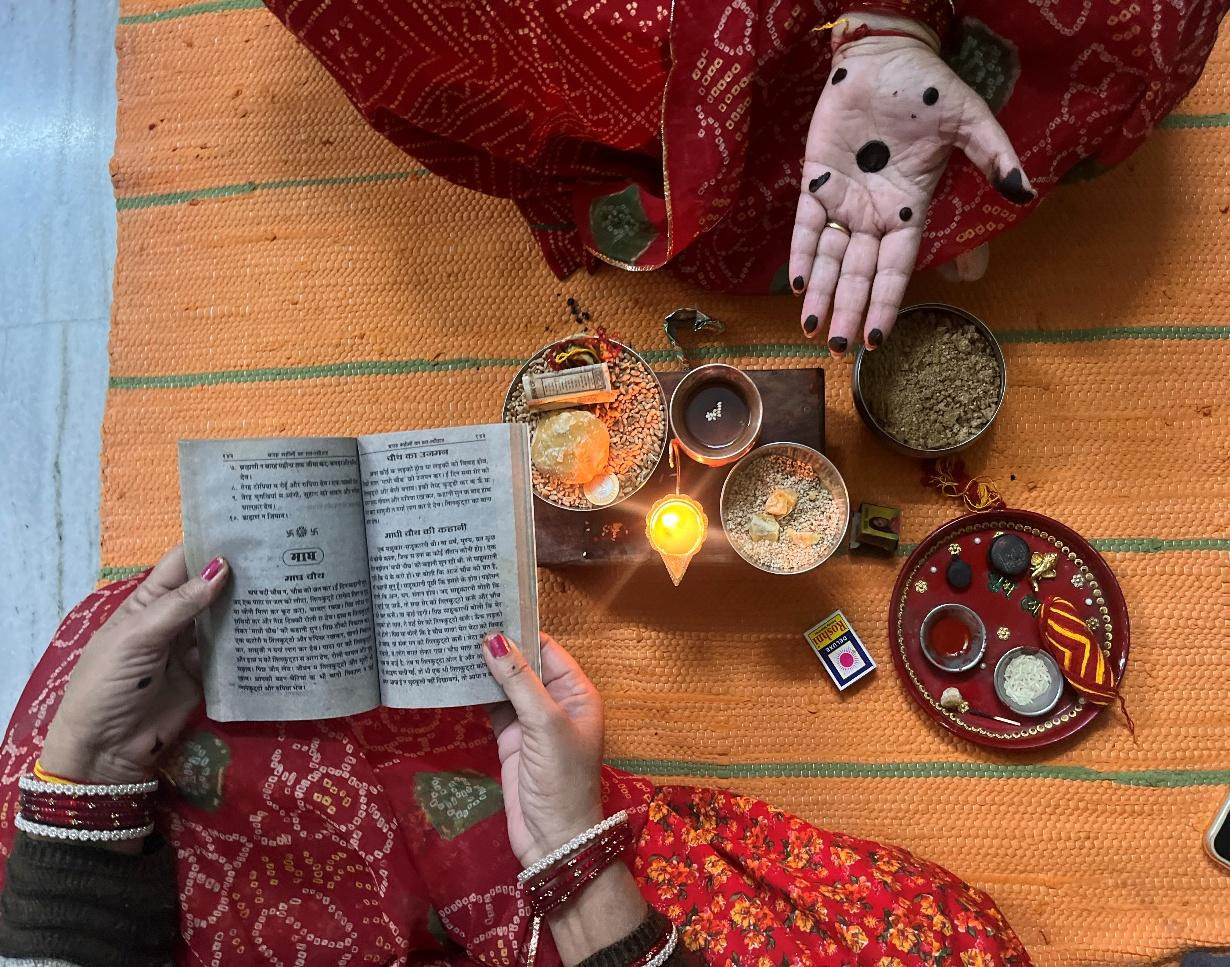

Sacredness of the cow and vegetarianism

The central themes that can be analysed behind this cultural fascism are the veneration of the cow and the glorification of vegetarianism. Both aspects are hailed as the tenets of the dharmic structures, which are “essential” to India. However, many scholars have rejected the idea that the sacredness of the cow and the vegetarianism associated with it was critical to the ‘Indian’ traditions. James Staples states, ‘Beef consumption is presented as a historically validated Hindu practice, referenced, for example, in the Rig Veda as suitable for everyday consumption and sacrifices.’

The central themes that can be analysed behind this cultural fascism are the veneration of the cow and the glorification of vegetarianism.

This can be read along with Ambedkar’s statement on vegetarianism, presented in the book Untouchables: Who were they and why they became untouchables (1948). He presents the adoption of vegetarianism by the Brahmins as a practice to overpower Buddhist tradition by adopting their tenets, non-violence against animals being a significant one.

In the current scenario, the values attached with vegetarian and non-vegetarian food are very distinct. While the former is considered the mark of purity and high social status, the latter is considered polluting. This also led people to adopt vegetarianism for social mobility, the practice M.N. Srinivas describes as ‘Sanskritization’, which is the process by which social groups of lower strata adopt the rituals and practices of the upper castes to attain social mobility.

The method of vegetarianism is placed on a morally high ground, often picturing it as “spiritually transformative.”

The method of vegetarianism is placed on a morally high ground, often picturing it as “spiritually transformative.” However, this morality placed on vegetarianism and its glorification nullifies various other communities’ culinary practices. Therefore, the historical habituation of meat, especially beef, is considered “morally impure”.

In this context, the practice of eating beef among the Muslim community is villainised, picturing the consumers as “barbarians”. Even though the consumption of beef existed long before, it is considered a “Muslim invention” that became popular after the Mughal period. It is considered as the many ways in which the Muslims are “polluting” the “Indian culture”. This should be read along with the various practices employed in the attempt of “othering” Muslims, reinforcing the “invader” narrative. The erasure of meat and beef from the public visibility is used to execute this narrative. The removal of meat from the hostel canteens of various colleges and the segregation of spaces for vegetarian and non-vegetarian food can be cited as an example. This leads to the gradual erasure of the food culture from the public memory, forcing people to accept the Brahmanical way of living and eating.

Ban on beef and cow products

Going one step ahead with the tabooisation of beef, various state governments have implemented a ban on beef, citing religious, environmental, and political reasons. As of 2015, eleven states and two union territories have completely banned the slaughter of cows, calves, bulls, and bullocks. However, the notion that a majoritarian ruling party can restrict the food consumed by the minorities themselves is a threat to the secularist fabric of the country, which, at this point, is completely torn. Even though there is evidence for the consumption of beef since ancient times, the forcing of Brahmanical eating habits on a larger population is the hallmark of the Hindu chauvinist policies in India.

Even if we are considering that the non-consumption of beef is part of (upper-caste) Hinduism, the imposition of it on a large non-Hindu crowd who have been historically consuming beef is nothing less than cultural terrorism. While we consider the non-consumption of beef as an essential practice of Hinduism, we tend to forget the practice of Kurbani, the Islamic sacrificial tradition to show their devotion to Allah.

While we consider the non-consumption of beef as an essential practice of Hinduism, we tend to forget the practice of Kurbani, the Islamic sacrificial tradition to show their devotion to Allah.

Here, the question arises – whose faith is valued more? This points to the fact that there are no equal citizens in this country – when one group can impose their food choices on the rest of the population, and one group can get killed for their food choices, there is a paradox of democratic principles.

Attack on livelihood

When the ban on beef is imposed, it does not only affect their dietary practices. Many Muslim communities in India also depend on cows as a source of their livelihood. Other than cow slaughtering, some Muslim farmers and pastoralists are affected by the inflation of fear with the association of cows.

For example, the Meo Muslims of Mewat who converted from Rajput clans are traditionally farmers who depend on cows for their livelihood. However, they are branded as cow slaughterers and their livelihood is at stake. The recent lynching of Nasir and Junaid, two Meo Muslims, in February of this year, is the latest episode in this chapter. Communities like Meos have been following their traditional livelihood for generations, leaving them with no other option of livelihood at the hands of Hindutva propaganda.

Contrary to the cow protection laws and lynchings, India has the highest export rate of beef. It has been continuously rising since the Hindutva government came to power. This shows the double standards of the governments as upper-caste people largely own the beef exporting business. However, the workers in the beef factories are Muslims and Dalits, again being vulnerable to attacks. According to Kancha Ilaiah, the Dalits and Muslims have been historically involved in livelihoods associated with the meat of the cow. This includes leather work and butchery – therefore, the discrimination does not stop with the food; it engulfs their lives altogether.

The horror of cow vigilantism

The mob lynchings in India have taken an organised and legitimate form now, with the installation of a cow protection committee and vigilante groups named “gau rakshaks”. According to IndiaSpend, ‘Muslims were the target of 55% (36 of 66) cases of violence centered on bovine issues over nearly eight years (2010 to 2017) and comprised 85% (22 of 26) killed in 66 incidents’.

The targets of the vigilante groups are primarily Muslims, as proved by the data. This invokes fear in the community, which is used by these groups to “discipline” and exploit the Muslims. The ban on beef and the violence associated with it is a major agenda in the witch-hunting sponsored by the BJP government against minorities in general and Muslims in particular.

Food as resistance

These tensions surrounding beef have led to two different results. There has been widespread fear in the beef-consuming communities of a possible attack by the Hindutva goons. We have witnessed Muslims being thrashed and murdered for storing and consuming beef, and we have seen Muslims being terrified at the idea of eating or distantly being associated with beef.

On the other hand, there is a development where beef has become a form of political dissent. Here, beef is politicised and carries a specific semantic density where it counters the majoritarian authority. The consumption of beef can also be considered a socially cohesive act, where the oppressed assert their identity and way of life.

References

- Adwaith, S., & Verma, J. Cow Protection sans Minority Welfare: Why the Beef Ban only Succeeds Where it Shouldn’t. International Journal, 1(4).

- Parikh, A., & Miller, C. (2019). Holy cow! Beef ban, political technologies, and Brahmanical supremacy in Modi’s India. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 18(4), 835-874.

- Staples, J. (2018). Appropriating the cow: Beef and identity politics in contemporary India.

- Ilaiah, K. (1996). Beef, BJP and food rights of people. Economic and Political Weekly, 31, 1443-1445.

- Sarkar, R., & Sarkar, A. (2016). Sacred slaughter: An analysis of historical, communal, and constitutional aspects of beef bans in India. Politics, Religion & Ideology, 17(4), 329-351.

- Bhattacharjee, N. (2012). Resisting Culinary Fascism. Economic and Political Weekly, 47(19), 4-5.

About the author(s)

Hajara Najeeb is an Independent Researcher working on issues of Minority Rights and Affairs, Gender, and Politics.